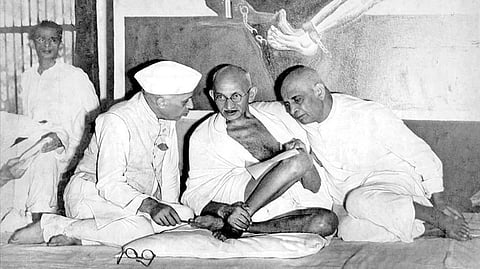

Sixteen Stormy Days: Tripurdaman Singh fills gaps in the riveting story of India’s First Amendment

In Sixteen Stormy Days, historian Tripurdaman Singh explores the reasons former Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru amended the Indian constitution barely six months after it was adopted. The author tells Anand Raj OK how the resulting First Amendment seriously damaged individual rights, but believes that history is rarely ever repeated

Last updated:

9 MIN READ

Sixteen

Stormy Days

Friday

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox

Up Next