Heart to heart: top cardiac surgeon answers questions we’ve always wanted to ask

Can an organ transplant recipient acquire some personality characteristics of the donor? Award-winning surgeon Dr Alla Gopala Krishna Gokhale tells Anand Raj OK the deep secrets of the heart

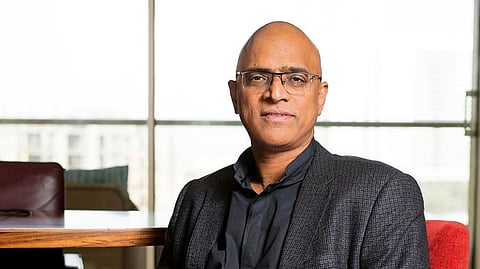

Tall, trim and athletic looking, Dr Alla Gopala Krishna Gokhale extends his arm to shake my hand. The grip is firm, even a tad powerful. Cheerful and with an optimistic disposition, the surgeon with a clean-shaven pate takes a sip from a bottle of water he is carrying, before settling into a sofa for a chat at the Raffles Hotel in Dubai’s Wafi where he is attending a conference on advances in cardiac and pulmonary treatments.

‘Unbelievable,’ he says, looking out the window that offers views of a slice of the Dubai landscape with glitzy high-rises neatly juxtapositioned with pools of greenery. ‘Unbelievable that this place was once a desert. Amazing vision of the Rulers.’

An award-winning cardio-thoracic surgeon who has a string of distinctions, including having performed India’s first heart-kidney combined transplant, Dr Gokhale at 60 still retains a certain child-like innocence with a sense of curiosity and amazement at things around him.

The Padmashri (fourth highest civilian award in India) award winner may have conducted more than 10,000 open-heart surgeries and 25 heart transplants — adult as well as paediatric — with a 98 per cent success rate, but he still continues to be fascinated by the human heart. ‘It’s really quite amazing — the working of the heart and the body,’ he says, before leaning forward and adding, ‘and the mind.’

He pauses waiting for his words to sink in. ‘As surgeons, we sometimes have to face some very strange queries and reactions from patients’ relatives,’ says the internationally renowned doctor. A smile plays on his face as he narrates an incident following a heart bypass surgery he performed on a 40-year-old man in the southern Indian city of Hyderabad. It was an incident that inadvertently also offered the doctor a peek into the way people’s minds work.

‘Every heart surgery carries with it some risks and so did that one too; some 2-3 per cent people lose lives or develop a paralytic attack or have some issues. So, when we emerge from the operation theatre, the patient’s family would usually be waiting outside eager to know the news of the surgery. They’ll be tense, some wouldn’t have had any meals or slept...’

That day too was no different. Emerging from the operation theatre he found the patient’s wife anxious and waiting to speak with him. ‘I was expecting her to ask me the usual question: "Doctor, how is my husband?",’ says Dr Gokhale. ‘But this lady had a strange query. "Doctor," she said, "When you opened my husband’s chest, did you see anyone else in my husband’s heart?"’

Dr Gokhale leans back guffawing. ‘I’m honest,’ he says. ‘It’s not a joke. This was a real question I was asked.’

What was your reply? I ask him.

‘I was nonplussed for a moment, but decided to take it in a lighter vein,’ he says. ‘I replied, "It is a professional secret; I cannot reveal what I saw".’

Picking up the thread, I decide to probe the distinguished heart surgeon about an intriguing theory that has often been discussed in books, movies and on television — whether an organ transplant can cause the recipient to mimic some personality characteristics of the donor.

The internet is home to many and varied cases — many of them unsubstantiated, says the heart-lung transplant and cardiothoracic and minimal access surgeon at Apollo Hospitals, Hyderabad, stressing on the word ‘unsubstantiated’.

A quick online search throws up fascinating stories on the subject — some well documented, thousands more not. At last count there were at least 70 documented cases of transplant patients developing personality characteristics of their donors. One woman in the US who enjoyed reading pop fiction all her life, found that her taste for literature had strangely changed after she underwent a kidney transplant in 2007 — Mills & Boon and the likes were replaced by Dostoevsky and Chekov.

A year later, a case was reported again in the US where a heart transplant recipient ended his life exactly the way his donor had — with a bullet to the head.

In 2010, a case emerged from Down Under where a heart-transplant patient developed a craving for a particular type of potato chips — which was a favourite of his donor who apparently used to gorge on it frequently.

In a similar case, an American woman recipient of a lung and heart found that she developed a liking to the same kinds of foods that her donor used to enjoy, even developing a craving for fast food — a tad shocking because the recipient was a dancer and choreographer who was particularly careful about her diet.

In the light of these examples, I ask Dr Gokhale, can the recipient of a heart, for instance, end up with the personality of the donor?

Dr Gokhale leans back and clasps his hands considering the question for a long moment. ‘Actually [experts] are scared to study this subject in detail,’ he says.

The heart, he goes on, is a very interesting organ. It is considered, at least in literature, to be the seat of all emotions — love, hate, desire, pain, joy. ‘But when I was in medical college I was convinced that idea was wrong — heart is not the seat of emotions. I believed the brain is really the most important organ when it comes to these emotions because we are taught in anatomy and physiology classes that we use the brain to think; the heart is only a pump that supplies blood to different parts of the body.’

He admits having read online reports about organ recipients who started exuding personality traits of their donors following a transplant. ‘I’ve heard of a heart recipient, a pure vegetarian, who began craving non-vegetarian food just like the donor used to.

‘[I’ve also read] another case where a patient who received a heart from a donor of the opposite sex was said to be behaving in a very different way from what he used to,’ says the doctor.

The heart specialist relates a story he read about a man in the US who was found murdered and whose heart was transplanted into a woman. ‘The story goes that the recipient began to have strange dreams of people [attacking her]. She was able to describe the attackers in such detail that the police used her descriptions to nab the murderers,’ he says.

Even as the doctor narrates more incidents that he says he read in reputed publications, he quickly adds that he himself has not studied the subject in detail for various reasons. ‘Only if we delve into this subject in detail will we be in a better position to talk about this with some authority,’ he says. ‘Until then we can only make personalised non-scientific observations.’

What is his take on the issue, I ask.

Dr Gokhale stares at his hands and considers the question. ‘It’s a fact that every cell has a memory called cellular memory. My feeling — and let me make it clear it is completely my view and non-scientific and I am talking like a layman — is that heart too has a memory.’

To underscore that last point, he adds: ‘You can take a heart out of the body and it will continue to beat for some time. That indicates it has a memory. More research needs to be done in this area. There are many things that we still are not able to understand or explain that easily.’

Dr Gokhale may not be the only person who thinks so.

In a 2015 report in The Telegraph, Professor Peter Friend, head of transplantation at Oxford University and a consultant transplant surgeon, was quoted as saying, ‘My gut feeling is we have no scientific rationale to support [the idea that the recipient of an organ develops certain personality characteristics of the donor], but we should also be open minded about things we can’t explain.’

The specialist in open-heart surgeries, Dr Gokhale too is a firm believer of having an open mind when it comes to research.

‘My gut feeling is that all cells have memory. Some probably express [the memory], some don’t. Amoeba has a memory. It is a unicellular organism but it has a memory system.’

He believes that extensive research needs to be done in this field. ‘But the thing is research into this field could make people a bit worried,’ he says.

In a different vein, I ask him why although thousands of heart transplants have been done worldwide — more than 200 were performed in India itself between 2016 and 2018 — do cardiac surgeries continue to grab people’s attention?

‘In many ways, heart transplantation is a lot different from other organ transplants like, say, the kidney or the liver. In the case of heart, for the procedure to be conducted, the donor has to be dead,’ he says, matter of factly.

But as technology advances, there could be two options — more powerful, smaller, less expensive mechanical devices, so patients don’t have to rely on a donor to make available a heart for a transplant; and growing human organs on transgenic animals — animals that have had a foreign gene deliberately inserted into their genome — which can then be harvested and placed in the human body.

He is pleased that technology is improving in leaps and bounds. While the initial heart machine weighed 3.5kg ‘and had to be placed in the stomach as space in the chest cavity was insufficient’, modern devices weigh just around 200g, he says. ‘So technology is improving. At the moment the devices are expensive. But soon they will become cheaper.’

Employing transgenic animals for growing and harvesting organs for human use is another growing area. ‘The animals’ genes are being modified so no diseases are transferred to human, and the hearts grown in them will be suitable and our body will not reject them.

‘Then there’s stem cell therapy where a heart can be grown outside then implanted into the body.’

Dr Gokhale, though, adheres to the ‘prevention is better than cure’ policy. ‘Maybe 20 years from now, we will have technology where heart conditions can be prevented.’

The cardiac specialist is into more than just surgeries. A philanthropist, he was instrumental in raising some 500 million rupees for a trust that he set up in his home town in Hyderabad offering cardiac care free of cost to poor people.

He is also on a mission to improve schools in the village he grew up in Guntur. ‘We need to provide the right kind of atmosphere for a child to grow up so he can make the most of it and rise up in life,’ he says. To that end, he set up a fund putting in 2 million rupees and with the help of wellwishers and some government units raised close to 10 million reupees, which was used to improve a rundown school in his village.

‘The government school I studied in was in a pretty bad shape — the roof was leaking, there were no water taps, no play areas… I said to myself, "I studied there without paying a penny and now that I am doing well, I should do something so other children will not suffer like I did".’

He believes everyone in society has a responsibility to do something for the community. ‘It’s a waste to not make use of your influence or goodwill to help the less fortunate,’ he says, adding he doesn’t think twice to request those with deep pockets to help make the world a better place for the less privileged.

‘I think anyone who has come up in life, has to lend a helping hand to others in society,’ he says. ‘Before you leave this world you have to give something back, some legacy for the people to remember you by. If when you are leaving the world you find that the world is the same as when you had entered, then you have not played your role.’

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox