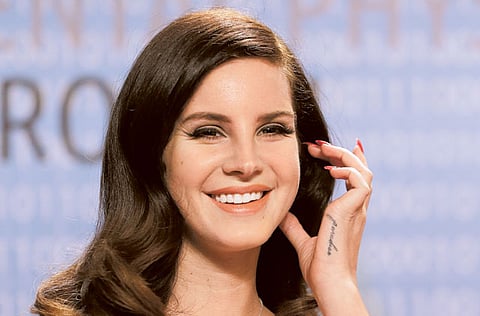

Lana Del Rey: ‘I wish I was dead already’

Her success has led to a vicious backlash, which shows in her brooding new album

“I wish I was dead already,” Lana Del Rey says, catching me off-guard. She has been talking about the heroes she and her boyfriend share — Amy Winehouse and Kurt Cobain among them — when I point out that what links them is death and ask if she sees an early death as glamorous. “I don’t know. Ummm, yeah.” And then the death wish.

Don’t say that, I say instinctively.

“But I do.”

You don’t!

“I do! I don’t want to have to keep doing this. But I am.”

Do what? Make music?

“Everything. That’s just how I feel. If it wasn’t that way, then I wouldn’t say it. I would be scared if I knew [death] was coming, but...”

We’re in New Orleans, a city not known for peace and quiet. A couple of blocks from Lana Del Rey’s hotel lies Bourbon Street, the scene of drunken rampages from morning till night. Head in the opposite direction and you can expect to be assaulted by the vibrant brass of the French Quarter’s street jazz musicians. Even inside Del Rey’s elegant suite there is carnage: suitcases half-exploded; bags of corn chips strewn across the floor. Even her laptop has been doused in tomato ketchup, temporarily thwarting our attempts to hear songs from her new album Ultraviolence. “Ewww,” she says, baffled as to how a condiment could have found its way inside the power socket.

And yet when we move outside to sit on her balcony, the scene is transformed into complete calm. “This place is magical,” she says, sparking up the first of many cigarettes. So serene is the setting, in fact, that it takes me by surprise when Del Rey begins to tell me how unhappy she is: that she doesn’t enjoy being a pop star, that she feels constantly targeted by critics, that she doesn’t want to be alive at all.

Throughout our hour-long conversation she keeps returning to dark themes. Telling her story — a remarkable one that involves homelessness, biker gangs and being caught in the eye of a media hurricane — also involves working out why a songwriter who has sold more than seven million copies of her last album, Born To Die seems so disillusioned with life.

Perhaps the logical place to start, then, is with the extraordinary reaction to Video Games, her breakthrough song in 2011. Arriving seemingly out of nowhere (although Del Rey had been posting her songs and home-made videos for some time), the video’s Lynchian creepiness cast a spell on almost everyone who saw it, causing the song to go viral.

Yet no sooner had the plaudits started rolling in (the Guardian voted it the best song of 2011) than Del Rey was placed under the intense scrutiny of endless blogposts and think pieces, with critics poring over her past for evidence of fakery: was her carefully studied aesthetic for real? Was she really just a major label puppet? Had her dad funded a previous bid for fame? Were her lips the result of plastic surgery? Was she really born as plain old Elizabeth Grant rather than emerging from the womb fully formed as the popstar Lana Del Rey?

I ask how long she got to enjoy the success of Video Games before the backlash arrived and she looks surprised. “I never felt any of the enjoyment,” she says. “It was all bad, all of it.”

Del Rey says she’s not scared to put another record out because she “knows what to expect this time”, but during the two-and-a-half years since Born to Die came out, she has often dismissed the idea of a follow-up because she’d “already said everything I wanted to say”. So what changed?

“I mean, I still feel that way,” she says. “But with this album I felt less like I had to chronicle my journeys and more like I could just recount snippets in my recent past that felt exhilarating to me.”

From the handful of songs I get to hear at the hotel, it’s safe to say the new material has plenty to get the bloggers worked up about again. Sad Girl, for instance, talks about how “being a mistress on the side, might not appeal to fools like you”.

She laughs when I ask where the inspiration came from: “A good question. I mean I had different relationships with men, with people, where they were sort of wrong relationships, but still beautiful to me.”

By wrong does she mean being the other woman?

She laughs again and looks away coyly. “I mean, I guess so.”

It’s not clear if Money, Power, Glory was originally written just to rile her detractors but it makes a decent stab at it by warning: “I’m going to take them for all that they’ve got.”

“I was in more of a sardonic mood,” she says of writing that song. “What I actually wanted was something quiet and simple: a writer’s community and respect.” She talks about that frequently: craving a peaceful life in an artistic community, away from the glare of a media that “always puts an adjective in front of my name, and never a good one”.

Like the woozy soft rock of the album’s teaser track West Coast, many of the songs on Ultraviolence are slow-tempo and atmospheric, ditching the hip-hop trappings of Born To Die for what she and her producer — the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach — call a “real narco swing”. Del Rey originally thought she had completed the album back in December, but after meeting Auerbach in a club and dancing the night away with him she realised she needed to record it all over again with his looser techniques — adding a more casual, California vibe to the sound by recording in single takes, with cheap microphones bought from the drugstore.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. One track, Brooklyn Baby, had been written with Lou Reed in mind: he’d wanted to work with Del Rey and so she’d flown over to New York to meet him. “I took the red eye, touched down at 7am and two minutes later he died,” she says.

If the critical sniping had died down, then Del Rey was finding her life invaded by other, more intrusive, means. In 2012, her personal computer was accessed by hackers and all sorts of information started to appear online: pictures, financial details, health records, not to mention her songs. “All 211 of them,” she sighs. “Just one more element of the unknown in my daily life.” She says she has no way of knowing who currently has access to several years’ worth of material, and no way of controlling the slow-drip leak of them online, including songs written for other people and at least one — Black Beauty — that was originally scheduled for Ultraviolence.

Indeed, when you start to look closely at Del Rey’s past three years, it’s not hard to understand why she might feel burned by her experience of stardom. You’re also forced to wonder why the pop stars who attract the most vitriol are so often solo female artists.

Inspired by Dylan

“People ask me this all the time,” she says. “I think they think there’s an element of sexism going on, but I feel that it’s more personal. I don’t see where the female part comes into it. I just can’t catch that feminist angle.”

I mention some current examples of musicians getting picked over in the spotlight: Miley Cyrus, Lorde, Lily Allen, Lady Gaga, Sinead O’Connor spring to mind.

“Well maybe those people are true provocateurs,” she says. “But I’m really not and never have been. I don’t think there’s any shock value in my stuff — well, maybe the odd disconcerting lyric — but I think other people probably deserve the criticism, because they’re eliciting it.”

What about her video for Ride, in which she hooks up with a succession of older guys from biker gangs (it received criticism for, among other things, appearing to glamorise prostitution)?

“OK,” she concedes. “I can see how that video would raise a feminist eyebrow. But that was more personal to me — it was about my feelings on free love and what the effect of meeting strangers can bring into your life: how it can make you unhinged in the right way and free you from the social obligations I hope we’re growing out of in 2014.”

How much did that video reflect her actual life?

“Oh, 100 per cent”

Hanging out with biker gangs and going off with different guys?

“Yeah,” she says, looking away again with another awkward laugh.

For all the accusations of being a fraud, Lana Del Rey seems to have lived a more rock’n’roll existence than your average pop star. She talks of teenage years spent “displaced — I didn’t have a home, didn’t know my social security number” and says she wasn’t in contact with her parents for about six years. Which must have made it extra galling when accusations came in that her career was funded by her father. “It was the exact opposite of that,” she says. “We never had more money than anyone we ever knew in town. My dad was a well-loved entrepreneur — he was interested in the early dawning of the internet in 1994 — but it wasn’t anything that ever translated financially.”

When those stories first emerged in the wake of Video Games she says she wasn’t even sure what her father was doing with his life: “And I don’t think he was too sure what I had been up to either. So it was interesting that they sort of fictionally put us side-by-side together and involved him in that story.”

Del Rey likes to describe the more tumultuous periods of her life in romantic terms: she says she’d often spend her nights wandering around New York — “West Side Highway, Lower East Side, parts of Brooklyn,” — meeting strangers and seeing where the night took them. “I was inspired by Dylan’s stories of meeting people and making music after you met them. I met a lot of singers, painters, bikers passing through. They were friends, or sometimes more. All people I was really interested in on impact.”

It sounds pretty dangerous.

Darker experiences

“Yeah, I was lucky, but I also have strong intuition.”

Does she still do it?

“Sometimes.”

Does anyone ever say: “Hang on — you’re Lana Del Rey!”

“Sometimes they do. About half the time they do, half the time they don’t. If they know who I am I can just leave, or I say it’s not a big deal, I’m just a singer.”

Are they not surprised to see you out wandering the streets?

“If I’m in LA then maybe. If I’m in Omaha, maybe not.”

When she was 18, Del Rey’s darker experiences — she has talked about being alcoholic — prompted her to take up outreach work helping those addicted to drugs or alcohol. It’s something she describes as her true calling and something she still does when she gets the chance.

“I live in Koreatown on the edge of Hancock Park [in LA], so I do different things where and when I can. It’s not just people with mental illness on the streets, but also people who, throughout the years, have lost identification information, that sort of thing. And I know what to do, I know how I can help, because I was that person.”

She says it feeds directly into her music. “A lot of my songs are not just simple verse-chorus pop songs — they’re more psychological.” She talks about tempo, and how she likes to reflect her mental state through a song’s speed: “When I played [the label] West Coast they were really not happy that it slipped into an even slower BPM for the chorus,” she says. “They were like: ‘None of these songs are good for radio and now you’re slowing them down when they should be speeded up.’ But for me, my life was feeling murky, and that sense of disconnectedness from the streets is part of that.”

She longs to be regarded as a serious songwriter, which is why those early accusations of fakery stung her so badly. Yet Del Rey only really needs to take a step back to see how well things have gone for her since she rode out that initial storm and began accruing the critical respect she feels she deserves. Outside music, too, her life appears relatively settled, even if she does describe her relationship with fellow musician Barrie-James O’Neill intensely: “We have a difficult road. He’s a very dark character. He has months on end where it’s a really dark stretch of writing and waiting, he has his total own world so…”

She falls silent. A waft of brass floats by and mingles with her cigarette smoke. I think about her live shows, such as the outdoor one she’s due to play later that night, during which she’ll respond to the constant screams — her fans are too busy taking photos to applaud — by letting her band jam away for 20 minutes while she wanders the photo pit, posing for selfies with fans in the front row. Surely during those moments she must love what she does.

“No,” she says. Then after another drag from her cigarette she looks down towards the busy street below and says. “I don’t know what I think. All I know is that, right now, I like sitting here, on this terrace.” She leans back and, for a moment, looks completely content in the silence.