The Last Royal Rebel

By Anna Keay, Bloomsbury USA, 480 pages, $35

The story of the Duke of Monmouth, Charles II’s illegitimate son, the “Protestant Prince”, is one of those curious historical tales where most of us know the end, but little of the life. There are many accounts of Monmouth’s invasion in 1685 in a desperate attempt to unseat the Catholic James II, of the defeat of his small army at Sedgemoor and of the judicial revenge on his followers by Judge Jeffreys in the “bloody Assizes”. But in Anna Keay’s fine biography this tragic finale is rendered still more bitter by her unfolding of Monmouth’s past career, his ever-changing hopes and fears.

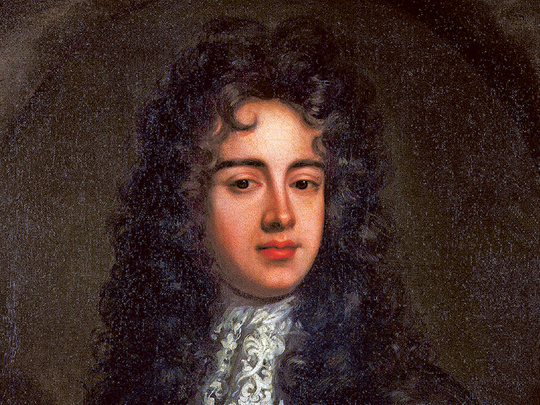

His early life, like his death, was marked by panic and passion, and Keay opens in the style of a historical novel, with conspirators lurking in the alleys of Brussels, while an eight-year-old boy “with bright eyes” walks with his mother, Lucy Walter. Lucy’s affair with the exiled Charles II took place in 1648 in the Hague, when they were both 18: James was born the following year. Although mother and child came to St Germain to meet Henrietta Maria, Lucy was forgotten when Charles sailed to Scotland to lead his ill-fated campaign, and when she took a succession of lovers, moving restlessly between France, the Netherlands and Commonwealth London, Charles tried repeatedly to kidnap his son. In 1658, on his third try, he was successful. By the end of that year Lucy was dead and James was in Paris, looked after by William, Lord Crofts.

Keay provides a fascinating portrait of the slippery, charismatic Charles II, and of his genuine love for his son. At the Restoration in 1660, James remained in Paris and soon his marriage to Anna, Countess of Buccleugh was arranged, ensuring a huge income from her Scottish estates. He came to England in August 1662, entrancing his father and the entire court, and by the time of his wedding — when he was 14 and Anna 12 — he had lodgings in Whitehall, garlands of titles, including Duke of Monmouth, and coffers filled by offices and royal pensions. In his teens he became a classic Restoration courtier — racing, gambling, dancing, womanising and brawling.

Keay makes telling use of account books to show the wild spending of Anna as well as her young husband. But Monmouth is very much her hero, as well as her subject: as he rides headlong to Chatham on hearing of the Dutch raid in 1667, she detects “a flash of something brave and brilliant that was yet to come”. By then he was determined to join the army, and to keep him safe Charles sent him to Paris to stay with his beloved sister “Minette”. The plan backfired — thrilled by the military power of Louis XIV, Monmouth was keener than ever to fight.

He was already captain of the life guards but his chance really came as commander of the British regiment helping Louis XIV against the Dutch, following the secret Treaty of Dover that Charles signed in 1670. The French command, Keay argues, left Monmouth a changed man, no longer a dissipated youth but an able commander, always concerned for his troops. In 1672, he led his men to take the apparently impregnable fortress of Maastricht — a feat soon played out in front of Windsor Castle in an astounding three-day display.

Military success, however, brought problems. Once his conversion to Catholicism was public, James, Duke of York, had to resign as lord high admiral. Monmouth, the hero of Maastricht, was an obvious replacement, but, loyal to his uncle, initially he refused high military command. At the same time, James’s conversion and his marriage to the Catholic Mary of Modena also raised widespread anxiety about the Protestant succession. Although James’s two daughters, Mary (soon to marry William, Prince of Orange) and Anne, were stoutly Protestant, parliamentary opposition began to grow. Led by the diminutive, terrier-like Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, the aim was the passing of an exclusion bill to bar Catholics from the throne.

In another twist, Charles — aware of the cost of conflict and the unpopularity of fighting troops who were now led by his nephew, William of Orange — signed a treaty to end the Anglo-Dutch war. Later, in the swings of international affairs, the tall, charming Monmouth would fight against the French by the side of the short, laconic William: in time, despite occasional froideurs, they became firm friends.

The brilliance of Keay’s account lies in her ability to convey the subtle intricacies of diplomacy and royal ambition — of Charles II, Louis XIV and William of Orange — and the detail of domestic politics. Yet, she also keeps a clear focus on Monmouth’s private story: his fraught marriage; his grief at the death of his small son; his adoration, yet growing wariness, of his father; and his final tender love for the heiress Henrietta Wentworth. The political story itself is domestic, familial: father and son, nephew and uncle. When Monmouth finally took over from the Duke of York as commander of the British army in 1678, the tension escalated. Jealous, and anxious at rumours that Charles had married Lucy Walter, the duke insisted that the phrase “natural son” (meaning illegitimate), long ago dropped, should be inserted into the document installing Monmouth as captain-general. Discovering this, Monmouth cut the word “natural” out.

Despite this, his loyalties were still with the court. Keay suggests that one turning point came when he was sent to quell the rebellion of the Scottish covenanters in 1679. Although he defeated the rebels at Bothwell Bridge, he was horrified at the Duke of Lauderdale’s ruthless persecution of landowners and nonconformists. His tireless arguments with the king for leniency came not from self-aggrandisement, in Keay’s view, but “from his own keen sense of injustice ... and the personal sympathy he felt for the wronged”.

When Charles II prorogued parliament to halt the exclusion bill, Monmouth became still more attractive to the opposition. For a while Charles sent the two dukes abroad, but both returned, and to his father’s horror Monmouth set out on a triumphant progress in the West Country. Later, he became implicated in plans for an uprising, and was saved only by a vague confession and his father’s love. He fled to Brussels with Henrietta, but was on the verge of reconciliation and return when he learnt of the death of Charles II in February 1685. The accession of the Catholic James II then spurred an invasion: the Earl of Argyll would land in Scotland, and Monmouth in Dorset, while others, they hoped, would rise up in Cheshire and London.

On June 11 Monmouth landed at Lyme Regis. Less than a month later, having heard of the collapse of Argyll’s campaign and realising that no other help would come, he faced defeat at Sedgemoor. He was discovered in a ditch and hauled to the Tower, and his bloody, mangled execution. Keay tells the story with heartbreaking crispness. The exclusion crisis ignited interest in politics, she concludes, but it was Monmouth who drew ordinary people. “And while he, and they, would fail,” she writes, “in the end their cause did not.”

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Jenny Uglow’s “A Gambling Man: Charles II and the Restoration” is published by Faber.