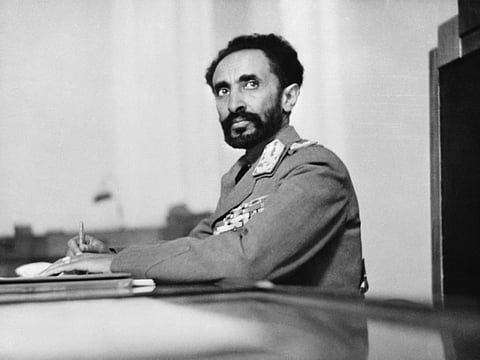

At last, a dignified biography of Haile Selassie I

King of Kings chronicles the life of one of the 20th century’s most misunderstood figures

King of Kings: The Triumph and Tragedy of Emperor Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia

By Asfa-Wossen Asserate, translated by Peter Lewis, Haus Publishing, 336 pages, $30

Haile Selassie is one of the most bizarre and misunderstood figures in 20th-century history, alternately worshipped and mocked, idolised and marginalised. This magnificent biography by the German-Ethiopian historian Asfa-Wossen Asserate (a distant relation of Selassie), and translated by Peter Lewis, is diligently researched and fair-minded; he is at last accorded a proper dignity. The book is manifestly a riposte to Ryszard Kapuscinski’s “The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat”, which portrayed the emperor, and indeed Addis Ababa’s entire Amharic elite, as a comic-opera laughing stock.

Selassie came to power as regent of Abyssinia, later Ethiopia, in 1916, but many of the myths around him originated with Mussolini’s invasion of the country in 1935. Selassie and his armies resisted, but he was eventually forced into exile. In 1941, after six years of brutal occupation, the Italians were defeated by British and South African forces and Selassie was allowed to return to his throne in Addis Ababa, where he remained in power until 1974.

One unexpected side-effect of the plunder of Selassie’s sub-Saharan state by a fascist power was to give Jamaica’s fledgling Rastafari movement impetus and a cause. The invasion became a dominant event in the Rastafarian narrative of black martyrdom. Selassie was seen as a manifestation of the one true god and a bulwark against “Babylon” (oppressive colonial society). The movement took its name from Selassie’s pre-coronation title, Ras Tafari Makonnen.

The Rastafarian movement was not the only radical current in Jamaica to co-opt Selassie. Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican apostle of black liberation, had condemned the ruler as a “great coward” for fleeing Mussolini’s troops in 1935, yet went on to dub him the “black Christ” of his Back to Africa movement. Inspired by Garvey, and believing in Ethiopia as the one true “Zion”, during the 1950s and 1960s some 2,500 West Indians and African-Americans went to live in the vicinity of Addis Ababa, in what is now Shashamane village. Only 300 of their number are believed to remain today.

There is a wonderful chapter on Jamaica here, in which Asserate recreates Selassie’s historic visit to Kingston in April 1966. A large crowd of Rastafarians swarmed the airport and banners showing the Ethiopian Lion of Judah rippled amid clouds of ganja smoke. Converging around the Ethiopian aircraft even as the propellers were turning, they sang praise to their god in human form, who they believed had come to redeem his Jamaican brethren. The impact of Selassie’s four-day state visit endured for many years, inspiring poems and songs — one of which, “Rasta Shook Them Up”, by Peter Tosh, contained introductory words in Amharic, the Ethiopian language.

Bob Marley, like Tosh, his fellow Wailer, believed that Selassie was a reborn messiah. The irony was that the emphasis placed by Rastafari on dietary laws and ganja-inspired “reasoning” of Old Testament scriptures was quite alien to the conservative Selassie, who was at pains to deny his status as the Rastafari Pope Almighty.

Meanwhile, the Ethiopian royal family promoted myths of its own, particularly its vaunted descent from King Solomon, the legendary third king of Israel. Selassie proclaimed himself a collateral descendent of Solomon’s wife, the Queen of Sheba (who may or may not have come from present day Yemen).

Yet for all the dizzying Semitic connections, Asserate reminds us, Ethiopia converted to Christianity in the fourth century AD, when the Ark of the Covenant was allegedly transferred there from southern Egypt. The Old Testament casket, lined with gold to accommodate the two tablets of the Ten Commandments, is said to reside today in the church of St Mary of Zion, near the Eritrean border.

The evidence for Ethiopia’s Semitic past is far from watertight (Rider Haggard made much of it in his schoolboy hokum, “King Solomon’s Mines”). But some believed that Selassie was the saviour whose coming had been foretold in the Old Testament. The belief was aided, Asserate notes, by the emperor’s “pure Semitic” features and “sphinx-like dignity”.

Selassie projected an image of himself as a paternalistic ruler. His ambition was to found a dynasty and “modernise” his country’s feudal system through a forward-looking (if paradoxically absolute) monarchy. His coronation in 1930 — attended by Evelyn Waugh, who Asserate describes as a “notorious sneerer” — drew ridicule for its display of sumptuously plumed and gold-braided uniforms and other regalia. Yet in lampooning Selassie as a tinpot Caesar, Waugh and other critics rather missed the point. The Napoleonic hats and gowns were part of Selassie’s vision of a parallel world equal to that of the white man. Why should the European powers have all the pomp and ceremony?

More contentious was Selassie’s tolerance of slavery. Most people-traffickers under his regime were Muslims, who converted their captives to Islam. As a condition of Ethiopia’s entry into the League of Nations, Selassie was required to eradicate the trade. He did what he could, and Ethiopia was admitted in 1923. Yet chattel servitude was not entirely eradicated. Bondsmen employed at the Addis Ababa palace were often actually “proud” of their position, writes Asserate. Slavery had long been a part of such African nation states as Dahomey, Oyo, and the Niger city-states.

With his unbending antipathy to any kind of social reform, from the 1950s onwards Selassie became out of touch and indifferent to the suffering of his people. When his 60-year rule ended, the subsequent “Red Terror” under President Mengistu, combined with Ethiopia’s border dispute with Eritrea, has left the African nation state depleted and corrupt.

Guardian News & Media Ltd

Ian Thomson’s “The Dead Yard: Tales of Modern Jamaica” is published by Faber.