Art and Lebanon

Two London exhibitions showcase contemporary artists with links to Beirut, exploring memory in a country still coming to terms with a war seen as unresolved

Arriving in Beirut in 1873, the Victorian artist and orientalist Frederic Leighton described it in a letter home as a “cheery, picturesque, sunny port” at the foot of Mount Lebanon. The future Lord Leighton was en route to Damascus, a source of the gorgeous ceramics that decorate his former studio-home in Holland Park, west London — now the Leighton House Museum.

The contemporary art currently on display there alludes to darker aspects of Beirut in the 20th century. Despite its arresting decorative beauty, it questions the continuing dominance of war in perceptions of the city and its artists.

Seven exquisite vases in the centre of an upstairs room appear from a distance to be typical blue-on-white Chinese porcelain. But the viewer’s serenity turns to horror upon noticing the motifs of fighter jets, tanks and rocket launchers. What look like blossoms turn out to be plumes from blazing tower blocks. Vase necks are embellished with falling shells. Each vase in “Yassin Dynasty” (2013), a porcelain series by the Beiruti artist and musician Raed Yassin, depicts a decisive battle in the Lebanese civil war of 1975-90, as described to the artist by fighters who survived.

Part of the solo show Kissing Amnesia, “Yassin Dynasty” recalls an ancient tradition of recording victories on ceramics — from Greek and Persian to Chinese. But the artist’s eye is on the human cost of battle. Using the style of Persian miniatures, he commissioned hand-painted copies from artisans in China. While the vases depict appalling suffering, their mass production afforded Yassin a detachment. “They’re beautiful objects, but closer up, you see the layers of trauma,” he says. “I wanted to take the war out of my life. Sometimes it’s good to make a declaration of intimacy with forgetting.”

Kissing Amnesia is one of two exhibitions in London of contemporary artists with links to Beirut whose youth (all are under 40) distinguishes them from the “postwar” generation that emerged in the 1990s. That internationally feted group of artists, who came of age during the civil war — among them Walid Raad, Akram Zaatari, Rabih Mroue and Marwan Rechmaoui — have challenged the amnesia imposed (along with the 1991 amnesty) on a war they see as unresolved.

Their oblique and quizzical approach to archives and photographs preserves documentary material while casting cautionary doubts on its veracity. This art grew partly in response to the way Beirut itself was being razed and reshaped to obliterate memory of the war, from the high-rise construction boom along the seafront Corniche area to the sanitised heritage of the Beirut Souks mall or Saifi Village, which resembles a pastel-painted ghost town.

I Spy With My Little Eye, currently at the Mosaic Rooms in London and moving on to Madrid and Cordoba, groups 13 emerging artists through the diffuse impact of Beirut on their work. While some of their families were displaced by the civil war, none of the artists had experienced it directly as adults. In “Let it ring” (2014), an installation by Charbel-Joseph H. Boutros, three retro telephones on the floor, arranged in a spectral triangle, are enough to evoke a diaspora. In another delightfully understated touch, the pine needles seemingly blown in through a window are in fact copper casts from Caline Aoun’s installation “Remote/Local” (2015). Though pine trees are a cherished emblem of Lebanon, they are a migrant species, both rooted and airborne.

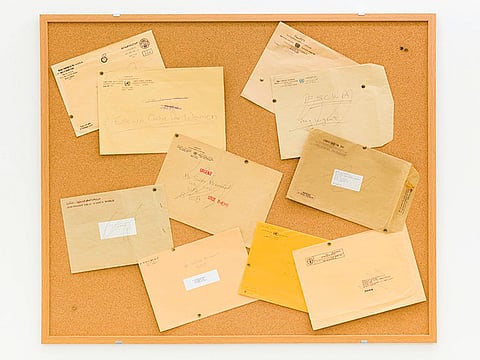

The curators, Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, also co-curated the Lebanese pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale, in which Zaatari’s installation “Letter to a Refusing Pilot” explored an Israeli airman’s act of conscientious objection. They see these artists as a contrasting new generation, less interested in collective than personal memory; clandestine observers of the everyday. Among found or ready-made materials are the official UN envelopes in Aya Haidar’s “Return to Sender” (2013), circulated in the Middle East, which she has doctored to create sceptical commentary (“UN stalls Development Programmes”). Though she grew up in London, Haidar heard stories of Lebanon from her grandmother as she taught Haidar how to sew. The artist is best known for tender, handmade embroidery (not in the show) that ranges from linen draped on buildings to the soles of shoes. “Making these stories into embroideries is a way to make them mine,” she says.

A dancer in Joe Namy’s silent video — part of “A Third Half Step” (2013-15) — improvises to music the viewer cannot hear, while subtitles offer a poetic commentary. Given that a “dance vanishes as it is danced”, the short piece becomes a superb meditation on time, memory, listening and movement. Namy, who grew up in the US, teaches sound art in Beirut, where he is frustrated by power cuts but also relishes the scope to take his art beyond galleries. At one of the “ubiquitous construction sites for apartments no one in Beirut can afford”, he collaborated with 20 Syrian labourers on a sound performance that turned the gaping foundations of a tower block into a “giant speaker — to make it sing a different tune”. Syrian workers, he adds, “do most of the hard labour but are usually hidden from society”. For one night, and the preceding months, they were “part of the orchestra”.

George Awde’s “Untitled (Beirut)” is a series of six photographs from 2012-14 of a group of Syrian boys against wasteland, the waterfront, and under a motorway. Yet these are intimate portraits, not social documentary, with an ambiguous familiarity between photographer and subjects. Hung off-centre or below eye level, they bring strikingly into focus what might otherwise have remained out of vision.

Deadpan humour is another key note. Siska’s short video “EDL” (2012) penetrates the modernist facade of Beirut’s electricity provider with the unspoken question of why, with such shiny equipment and high hopes, power cuts are still a daily hindrance. Pot plants beside the lift and a worker in slippers heighten the comic absurdity. In another ironic swipe, in Pascal Hachem’s installation “Non-Essentialism” (2014), a typical Lebanese flatbread suspended above a mirror appears to bear a “made in China” stamp on its underside.

Beirut-based Tala Worrell, at 24 the youngest in the show, describes herself as “a painter, not an artist”. For her, the canvas is “a window and a screen so you can really imagine something new”. Her barely dry oil painting, “Earth”, has rectangular fragments of landscape in little windows or screens, while “Lookers” shows the backs of people peering out of them. She was inspired by a wish to paint landscapes without the desire to go outdoors, leading her to ask: “If there is a nature, what is it now?” The canvases, arranged on paint tins as though still in a studio, lay bare the painter’s thought processes.

Like several of these artists, Worrell, who grew up in the US and Abu Dhabi, acknowledges a huge debt to the postwar generation. That indebtedness is clear, too, in Lara Tabet’s collaborative installation “The Reeds” (2013), whose ambiguous photographs blur lines between the staged and the real. Taken in a Beirut sexual cruising ground, the furtive images are presented in a box on a desk, for the viewer/voyeur to sift through, as though in an undefined, and faintly sinister, official investigation.

–Financial Times

I Spy With My Little Eye runs at The Mosaic Rooms, London, until August 22 and Casa Arabe, Madrid from September 17-November 22, and Casa Arabe, Cordoba from December to February 2016.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox