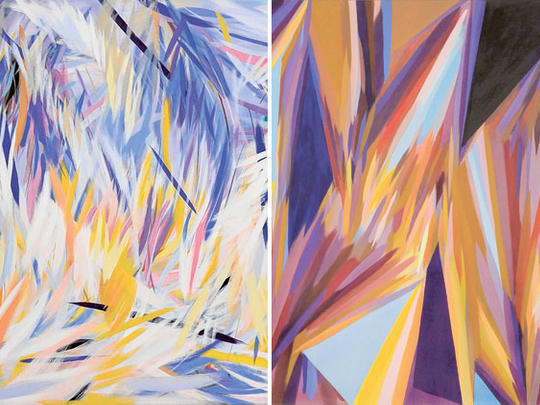

Samia Halaby is a pioneer and innovator of abstract painting in the Arab world. The New York-based Palestinian artist is known for her vibrant, monumental paintings and her path-breaking experiments with abstraction. Her latest work, titled Trees and the High Rising City, indicates that the 75-year-old artist continues to search for new ways to interpret the world around her. The paintings capture the ethos of a modern metropolis by combining the hard edges and angular perspectives of architecture, the softer textures of trees and other greenery and the movement of people and cars. This combination of elements is rarely seen in abstract art and this is the first time Halaby has explored these simultaneously in her work.

"I have taken a new direction in both subject and form. These were difficult paintings to create and they are hard ones to contemplate — devoid of sentiment, softness or ornament. I painted with a combination of intuition and intellect, bold impulsiveness and careful deliberation. I combined soft and hard and broke many of my own rules. I felt I had no historical precedent and it was the first time in a long painting career that I proceeded with a fear of failure," Halaby says.

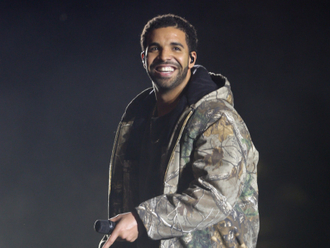

Born in Occupied Jerusalem in 1936, Halaby has lived away from her homeland as an exile for most of her life. She moved to the United States in 1951, where she studied design and fine art. She has taught at various American universities and was the first full-time female professor to teach at Yale School of Art. She has also been a life-long activist, supporting the Palestinian cause in various ways. Weekend Review spoke to her about her life and work. Excerpts:

Why did you choose to be an abstract artist?

I was emotionally and intuitively drawn to abstract art. As an art student, I committed myself to abstraction because I felt it was the art of our time. The 20th century was a see-saw between forward-looking and backward-looking art. I saw that the Materialists of the Soviet revolution, the Cubists and all the artists who moved forward in that century were abstract; and that abstraction abandoned illusion and all the subject matter of praising the rich and the ruling class and religion and everything that came with illusion. Abstraction has contributed to imaging in science, to graphing ideas and other areas. I still feel abstraction is the language of the future.

Has your work been influenced by Islamic art?

When I studied Arab architecture and geometric abstraction, I discovered attitudes that were close to my heart and which moved me. I feel an emotional identification when I enter a mosque and see the Islamic art. And I am shocked when this art is called decorative, because I think it is as profound as the art of Mondrian or Michelangelo. Islamic art is idealist in the sense that it is about religion and contemplation. My art is not about religion but it builds on the abstraction of both Arab art and the Soviet constructivists.

Despite living abroad, how did you maintain this strong connection with your roots?

I was 14 and strongly aware of my Arab identity when I moved to the US. And I am connected to my roots, because when you live abroad and experience the racism and rejection, it gives you a different and clearer perspective. But I do not like this talk about roots, because it suggests that an artist's only history is the art from their region. This puts everybody into cubbyholes, preventing artists from aspiring for the highest. I rejected this from the beginning and tried to understand all art history, how painting developed and what it means to society.

Why did you feel fear while working on your latest paintings?

Abstract paintings are usually homogenous, but when I look around the city I see high-rise buildings, some trees behind them, chunks of sky and people walking around. I wanted to show all these things together and did not know how to do it. To achieve this I broke many of my own rules regarding perspective and shading. Instead of my usual free brush strokes, I had to be controlled and I used intuitive measurements rather than precise geometric logic. I felt fear because I did not know how this experiment of combining the hard and the soft would turn out. But I am happy with the result.

What motivated you to write ‘Liberation Art of Palestine'?

The art of the intifada was a home-grown school of art, which developed in the 1970s and the 1980s in Beirut, Gaza and the West Bank. The Israelis have been destroying the paintings and hence it was important to document them. I interviewed 46 artists based in Palestine and gathered 62 pictures of the paintings, so the book documents the art of the intifada like never before.

You have often moved away from abstraction to do powerful, figurative paintings about Palestine. Tell us about the inspiration for these works.

Paintings come from the heart and there are two significant series that I have done on Palestine. In the first I documented the olive trees, because what they do to the olive trees is the same as what they do to us. So there is the refugee tree, the beheaded tree and others painted in an Illusionistic way. The other set documents the Kafr Qasim Massacre.

I interviewed witnesses and did a careful essay of every aspect of the massacre. I got a roster of names of the victims and based my drawings on their photographs. I pretended to be a camera and used a Renaissance style to draw not dead bodies but the people just a few seconds before they died, so that viewers are confronted by their faces and humanity.

In your painting, ‘Gaza', you wrote about your desire for the intifada to be globalised and about Gaza's resistance against all odds rescuing the dignity of the Arab world and giving hope to humanity. As an activist, how do you feel about the present uprisings in the region?

Gaza was a symbolic and an optimistic work. But my activism is not expressed so much in my painting as in more practical ways. I have organised demonstrations, worked with pro-Palestine groups in New York and held exhibitions of Palestinian art in the US. What is happening in the region is a good beginning and gives hope for humanity. But it must go a lot further.

Can art make a difference in politics?

No, not at all. The best contribution artists can make to Palestine is to be the best artist they can be, so that people can say "here's a great artist and they are Palestinian". The rest is contribution to art and to international human culture.

How do you feel about exhibiting your work in Dubai?

Exhibiting my work in the Arab world is very special and Dubai, being a meeting place for the East and the West, is becoming an important international centre for art.

Trees and the High Rising City will run at Ayyam Gallery, Dubai, until April 28.