The Fed: serial bubble blower

The bank's history of overreacting often leads to an injection of excess liquidity

On January 3, US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke delivered a major speech at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association. In his formal paper, Monetary Policy and the Housing Bubble Chairman Bernanke argues that the Fed's monetary policy was not responsible for the US housing bubble. He claims that faulty regulation was the primary culprit.

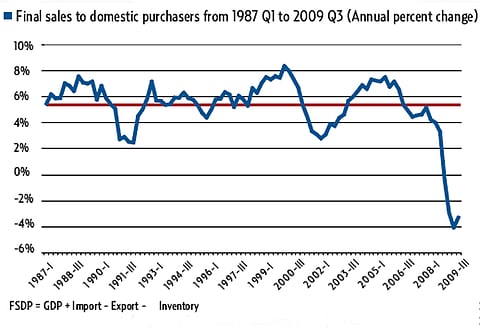

Chairman Bernanke's claim is a great canard. The Fed is a serial bubble blower. Let's first consider the Fed-generated demand bubbles. The easiest way to do this is to measure the trend rate of growth in nominal final sales to US purchasers and then examine the deviations from that trend. As the accompanying chart shows, nominal final sales grew at a 5.4 per cent annual rate from the first quarter of 1987 through the third quarter of 2009. This reflects a combination of real sales growth of 3 per cent and inflation of 2.4 per cent.

The nominal final sales measure of aggregate demand contains three significant deviations from the trend (demand bubbles). The first followed the October 1987 stock market crash. The second followed the Asian financial crisis and the collapse of the Russian rouble and Long-Term Capital Management in 1998.

The Fed's zigzag pattern is clear: an overreaction to a so-called crisis, resulting in the excessive injection of liquidity (a sales boom), followed by a draining of liquidity and a recession (a sales slump).

The most recent aggregate demand bubble wasn't the only one that the Fed was pumping up. The Fed's favourite inflation target — consumer prices, less those for food and energy — was increasing at a regular, modest rate. Over the 2003-2009 period this metric increased by 14.3 per cent. The Fed's inflation target metric signalled "no problems." But abrupt shifts in major relative prices were underfoot. Housing prices measured by the Case-Shiller index were surging, increasing by 44.7 per cent from the first quarter in 2003 until its peak in the first quarter of 2006. Share prices were also on a tear. The most dramatic price increases were in the commodities. Measured by the Commodity Research Bureau's spot index, commodity prices increased by 92.2 per cent from the first quarter of 2003 until their peak in the second quarter of 2008.

Main lesson

The Fed should dust off the works of economists from the Austrian school, particularly Prof Friedrich Hayek's. The main lesson from the Austrians was their extreme scepticism about the exclusive reliance on one magic index — the price level — to guide central bank policy. Indeed, Hayek stressed that changes in general price indexes don't contain much useful information. He demonstrated that it was the divergent movements of different market prices during the business cycle that counted. It's time for the Fed to dump inflation targeting.

Chairman Bernanke's denial of the Fed's culpability raises an interesting question: how can the Fed make fantastic claims without being brought to account? In a 1975 book of essays in honour of Prof. Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom: Problems and Prospects, Prof Gordon Tullock wrote: "…it should be pointed out that a very large part of the information available on most government issues originates within the government. On several occasions in my hearing [I don't know whether it is in his writing or not but I have heard him say this a number of times] Milton Friedman has pointed out that one of the basic reasons for the good press the Federal Reserve Board has had for many years has been that the Federal Reserve Board is the source of 98 per cent of all writing on the Federal Reserve Board."

Does the mighty Fed really control the information flow and ultimately the press? Prof. Larry White subjected this question to what the Fed must have thought was the indignity of factual verification. His findings support Friedman's assertion. In 2002, 74 per cent of the articles on monetary policy published by US economists in US-edited journals appeared in journals published by the Fed, or were written (or co-written) by Fed staff economists. The Fed's capacity to write and re-write history dominates the information flow. It's no wonder the Fed's canards give it few worries.

Speaking of economic history, one thing that the purveyors of monetary policy (and all prudent investors) should become well versed in is a piece of business-cycle history that has apparently passed them by — namely the little-known, but essential, 18-year real estate cycle. This cycle goes hand-in-hand with Austrian business cycle theory in which booms and bubbles are created when central banks set short-term interest rates too low, allowing credit to expand artificially. As Prof. Mason Gaffney characterises it: "Bank credit swells and shrinks in synch with the land cycle. The two interact in a positive feedback process: swelling bank credit raises land prices; buyers need more credit to purchase the land; the appreciated land then serves as collateral for more bank loans, and so on."

Land prices eventually peak and then construction activity peaks. This is followed by a peak in the general economy. In short, land prices are a leading indicator of both construction activity and general economic activity.

The accompanying table tells this story. It also shows that, with the exception of Second World War, the peak of most real estate cycles is roughly every 18 years. These data talk, and the most interesting thing they say is that every 18 years we can expect the culmination of a credit-fuelled real estate and ensuing business cycle. This, of course, doesn't imply that all recessions are preceded by a real estate cycle.

Steve H. Hanke is a professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington, DC.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox