A realistic option nobody dares give a chance

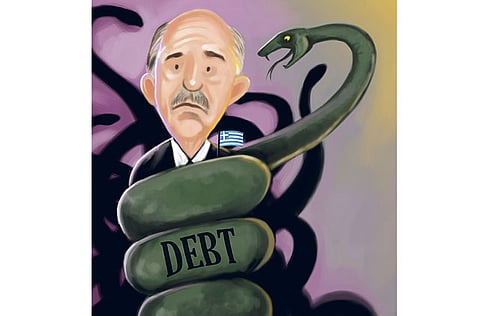

Would it be political suicide for Greece to default on its debts, as some would have us believe, or a smart move?

From George Bush to George Osborne, many stupid and disingenuous things have been said during the financial crisis. But some sort of prize really ought to go to Lorenzo Bini Smaghi.

His seat on the executive board of the European Central Bank makes Bini Smaghi one of the most important econ-omic officials on the continent. He votes on whether interest rates in the Eurozone should go up or down. He's had a hand in the bailouts to distressed nations within the single-currency club. And two weeks ago he warned the struggling Greeks: "Default or debt restructuring is a dramatic economic and social event for the country which experiences it. I would call it political ‘suicide' which leads many into poverty."

What's wrong with this argument? It's the sort of everyone-says-it-so-it-must-be-true argument that's been a hallmark of European policymaking ever since the banking crisis broke out.

When it comes to spouting conventional nonsense, Bini Smaghi has a fine pedigree. In 2007, he wrote: "The Irish example shows that it is possible to prosper in the monetary union while having a higher potential growth rate than the rest of the union." It was the spectacular wrongness of this conclusion that prompted bloggers to award the eminent central banker a new name: BS.

Right now, though, BS has many friends. Hardly a day goes by without a heavyweight from Frankfurt or Brussels warning Athens that unless it keeps on paying its loans in full and on time, dire consequences will unfold: investors will never lend to the government again, nor will foreign businesses come to the Med.

Missing element

Even those who can see that this is impossible for prime minister George Papandreou, with his weak, divided government and wrecked economy, can barely bring themselves to use the word default, they talk instead of reorganisation or restructuring. Last week, a spokesman for the European Commission floated the idea of debt re-profiling. This, he assured journalists, was "a different concept from debt restructuring. It doesn't involve... the same players and doesn't have the same consequences." Reports that he was waltzing on the head of a pin throughout the briefing are yet to be confirmed.

At its best, this is economic diplomacy by euphemism; at its worst, it is pin-striped loan sharkery. Either way, what's largely missing from this debate is any discussion of what the evidence shows for countries that do default. Which should perhaps not come as a surprise because, if it were more widely disseminated, voters in Greece, Ireland and Portugal might well be calling far more loudly and confidently for their governments to renege.

Over the decades, economists from Ken Rogoff to Barry Eichengreen have queried the notion that default is, to use Bini Smaghi's term, "suicide". But the best recent paper I have come across on the subject is from October 2008, just after Lehman Brothers collapsed, and was written by Eduardo Borensztein and Ugo Panizza at the International Monetary Fund. Given that the IMF spends most of its time telling bust governments to keep to the path of fiscal rectitude, you might expect these two to write about the dangers of default. Far from it.

First, Borensztein and Panizza put together a history of countries that defaulted between 1824 and 2004. Then they look at the short- and long-run consequences of the default.

Their conclusion? "The economic costs are generally significant but short-lived... we almost never can detect effects beyond one or two years."

It's true, as Bini Smaghi and his colleagues claim, that investors don't lend to countries that welch on their loans but the informal embargo lasts for months. The IMF researchers show what the governments of Argentina and Russia could tell you from recent experience: markets have fairly short memories.

Even the interest rate on loans to disgraced countries falls within a couple of years from the punitive to the near-normal.

Spending cut burden

None of this is to say that national bankruptcy is as easy as checking into a spa. Angry creditors have a nasty habit of setting Manhattan lawyers on poor African countries if they think they stand a half a chance of getting their dollars back. But coming clean and admitting that you can't pay your loans is a viable option for an administration that has run out of other options.

Athens is now at that point. Under the weight of historic spending cuts, the Greek economy has come apart faster than an MFI bookcase under a pile of Encyclopedia Britannicas.

Greece's budget overdraft has rocketed way past international official forecasts, and going by markets last week investors would only be willing to lend to Athens at a 17 per cent interest rate. You could get better terms from your credit-card company.

So why doesn't Athens just give up? Surely not because its economy would do any worse, but because the banks, in Germany (which holds $26 billion of Greek debt) and France (which owns $20 billion) and in Greece, would then have another brush with insolvency. But the answer would be to deal with the banks by giving them more money or just taking them over rather than crucify an economy.

For Costas Lapavitsas, an economist at the School of Oriental and African Studies just back from Athens, the situation represents only one thing. "It's the triumph of the banks," he tells me.

"The lenders in Greece and abroad are being given preferential treatment over the Greek people."

— Guardian News & Media Ltd