Algeria yet to heal from Black Decade scars

Hundreds of thousands believed to have died in the brutal 11 year war between Islamists and army

Abu Dhabi: In the 1990s, Algeria was thrust into a brutal civil war between armed Islamist groups and the Algerian Army. Twenty years ago today, on September 22, 1997, a band of around 100 men from the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), carrying Kalashnikovs, hunting rifles, fire bombs, and machetes, descended on the sleepy town of Bin Talha, 20km south of Algiers.

Meant as punishment for supporting the Algerian regime, the killings were brutal and happened over five fours.

Official sources put the final death toll at 89, but the people of Bin Talha, who dug the graves for the men, women, and children who had been so brutally cut down, said at least 400 had been killed.

The town was in the middle of the “Triangle of Death”, an area south of the capital that saw some of the bloodiest massacres in the course of the war.

Twenty years since the massacre, its memory looms large.

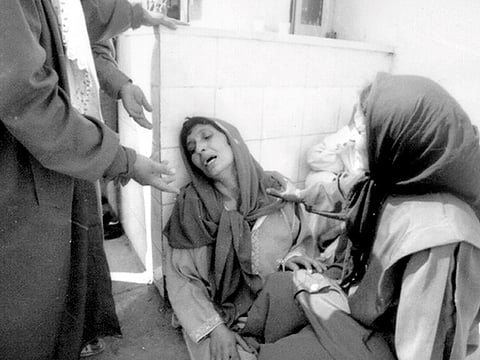

The incident was immortalised by the photograph of a grieving woman – the ‘Madonna of Bin Talha’ – who had collapsed on the hospital floor mourning three family members.

It was splashed across the pages of newspapers worldwide, and the image became the symbol of the civil war.

Since the end of the war, Algerians have largely preferred to keep the decade in the closet—a memory that cannot be forgotten, but one too painful to discuss.

The 1990s: Black Decade, Dirty War

Some call the 1990s the ‘Black Decade’, and the conflict the ‘Dirty War’. With the winds of democracy blowing across the post-colonial world in the 1980s, Algeria became a political laboratory for the Arab world.

The National Liberation Front, known by its French acronym FLN, had ruled the country since its independence from France in 1962. But the party, which was the vanguard of the revolution, lost dynamism and street credibility.

With falling oil prices in the late 80s, the state coffers were also emptying and thousands took to the streets in the 1988 riots.

The government sought compromise with an increasingly mobilised population.

Constitutional reforms and political pluralism were meant to engage communities and allow free expression in Algeria. But, like we have seen in multiple countries since 2011, the opposite happened.

Islamists, not democrats or youth, were the only group able to coalesce and organise nationally.

They enthralled the country with their religious discourse, as well as intertwined economic and social demands around the myth of an ‘Islamic’ state.

The Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) contested and won nationwide local government elections in June 1990.

In the first round of parliamentary elections on December 26, 1991, the FIS won 188 of the 430 seats outright.

But, when a victory at the ballot was closest, it also became clear that elections were merely a means to an end—which would serve as a cautionary tale for the Arab world.

For the FIS, and a nucleus of so-called ‘Afghan Algerians’ (men returning from fighting against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan), the goal was to establish an ‘Islamic’ state.

The party’s official slogan during the legislative elections was: “No constitution and no laws. The only rule is the Quran and the law of God.”

On December 29, 1991, three days after their victory, leaflets were circulated on the capital’s streets proclaiming that, among other things, women would no longer be allowed to work and that the wearing of the hijab was compulsory.

The landslide Islamist win triggered the resignation of the President Chadli Bin Jedid.

With the FIS poised to seal their victory in the second round of elections, the army intervened and cancelled the elections.

Troops were deployed across the country, a state of emergency was imposed, and FIS leaders were arrested. Armed sympathisers of Islamist parties, led by the GIA, launched a guerilla campaign against the state.

From December 1991 to February 2002, the war claimed tens, maybe hundreds, of thousands of lives.

Thousands of families fled Algeria. Refugees would later emerge from Algeria speaking of coordinated attacks against civilians: death squads, massacres, abductions, kidnappings, rape, and the murder of entire families.

By the turn of the new millennium, the Algerian security apparatus had succeeded in infiltrating and dividing the insurgent groups.

Negotiations between the government and more moderate groups brought down the levels of violence.

Eventually, an uneasy ceasefire held. After Abdul Aziz Bouteflika won the 1999 presidential elections—in which he was the only candidate—he struck a substantive deal with Islamists, and eventually rolled out a general amnesty for crimes committed in the 1990s by all sides.

Modern Algeria: Post-conflict, post-memory

All Algerians recognise the profound impact the bloodshed has had on the collective memory and psyche of the nation today.

Walid Naamane, an analyst on North Africa, contrasted his country’s experience with those of similar national catastrophes: “Unlike Tunisia’s recent attempt to shed light on years of dictatorship through a ‘Truth and Dignity Commission’, or Rwanda’s collective remembrance and memorial of the genocide of 1994, Algeria has no museum, no national investigative process, or comprehensive truth commission to reflect on our catastrophe.”

Naamane, who lived through this difficult decade, added: “The memory of the 90s is a nightmare lived privately; its details are discussed in hushed tones.”

Today, Algeria remains a shadow of what it could have been.

The North African giant has immense economic potential, but remains grounded by a lack of visionary outlook, ineffective, if not corrupt, economic practices, and the ideological shadow of a long and brutal civil war.

With so much baggage, the complex nation is a slow moving ship, often unpredictable even to those that understand it best.

In the wake of the Arab uprisings of 2011, many viewed Algeria’s memories of the Black Decade as the antidote to nationwide unrest – the so-called “Algerian Exception”.

On paper, the conditions were ripe for change.

Even today, many point to oil prices below the government’s break-even point and demographics where 66 per cent of the population is under 30.

The government cut expenditures by 14 per cent in the 2017 while introducing new taxes and tariffs, as well as cutting benefits and subsidies.

National unemployment rates hover around 11 per cent, according to official statistics, and those between the ages of 15 and 24 account for almost 40 per cent of the country’s unemployed.

In all its complexity, the irony of the Algerian system—in both state building and political evolution—has been to perpetually find ways to gain time.

The Algerian leadership is widely seen as shortsighted.

Since the FLN first took power, critics say it’s leaders have failed to push the youth to imagine and dream big.

There is no Vision 2030 or ambitious national plan for the country.

Instead of imagining a future, critics say, leaders have been accused of harkening back to the past, using diatribes against French colonialism to drum up nationalistic fervour, or falling back to the horrors of the civil war in moments of insecurity.

People are left to vent their frustration with opaque public institutions and nepotism through satirical YouTube channels—a few have turned to art and music to express themselves.

However, by and large, Algerians are not interested in regime change perhaps because of the nightmarish alternative they experienced.In ‘Let Them Come’, a film that premiered regionally at the 2015 Dubai Film Festival, Salem Brahimi, the director, depicts a realistic and deeply emotional account of how Algerian society lived the horrors of the Black Decade. The film shows how the barbarity of war and terrorism asphyxiates society, occupying both a physical and mental space. Brahimi asks himself: “How did we generate such barbarity? People who did that were our neighbours, our brothers. It’s easy to say the bad guys are the others. It’s very hard to admit that they came from our midst, and everybody should be asking themselves about this.”

-Tarik Chelali is an Associate at the Delma Institute, an Abu Dhabi-based risk advisory firm