Road to recovery

Amid telltale signs of the 37-year civil war in Jaffna, the erstwhile LTTE stronghold in Sri Lanka slowly gets back on its feet

After 37 years of civil war, business is slow in Jaffna for the few taxi drivers with their collection of Austin Cambridges, Ambassadors and Morris Minors. For Rs10,000, Mohan will take me for a day's drive to Kilinochchi, about 60 kilometres to the south down the dangerous A9, a road that has only been reopened to civilian traffic — as long as you have permission from the Sri Lankan military to travel it.

"Very good car," Mohan taps the dashboard of his 1960 Austin Cambridge. "England built," he says.

I muse that the definition of an English engineer is one who can make a solid block of metal leak oil.

"All original," the driver continues. "Engine, carburettor."

Tyres too, I say to myself, having noted the bald rubber when I hired Mohan in the town square.

He puts two hands to the pane of glass on the rear passenger's door, pushing it down to open it. Clearly, the British-engineered window rollers have exceeded their best before date.

As a foreign journalist, my hard-obtained written permission prohibited me from travelling by road north to Jaffna. Instead, I flew under military supervision to their airbase at Palaly, just outside the largely Tamil town which was the focus of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) resistance for years. But the note didn't say I couldn't travel south.

The Nurse Teaching Hospital in Jaffna is now occupied by a military unit, young soldiers casually cradling their Chinese-made T56 semi-automatic rifles.

The T56 is essentially an AK47, formerly the standard weapons' issue to communist bloc countries. The T56 though, is a modern version but 99 per cent the same as the rifles which have become ubiquitous in most developing countries. AK47s have been around longer than Mohan's 1960 Austin Cambridge.

"Here are shooting and bombing," Mohan says, pointing to the hospital. True. Though considered a sanctuary, Indian troops in Jaffna, as part of the Indian Peace Keeping Force, claimed to have come under fire from the building in October 1987. They stormed it and about 70 people died.

In all, an estimated 100,000 people died in this tear-shaped island's long and bloody civil war, a conflict so brutal in ferocity that the likes of Al Qaida still use the tactics developed by the LTTE. It was the LTTE who developed the suicide bomb, using diehard supporters as human weapons, bringing terror and chaos to Colombo and all across this beautiful land, all in a furious campaign for a Tamil homeland in this northern peninsula 35 kilometres from India.

War was hard fought, peace harder to come. And even now how that peace was won is disputed. The UN claims war crimes were committed by Sri Lankan forces during the last months of a bitter war when the last of the LTTE fighters used civilians as cover. The Colombo government under President Mahinda Rajapakse strongly denies those claims, and if war crimes were committed, it is the LTTE terrorists who are guilty.

Either way, the truth is hidden in a bomb- and bullet-scarred landscape, mined and shelled and drenched in the blood of Tamil and Sinhalese, LTTE and military, Sri Lankan and Indian.

Now a plethora of international agencies are here, such as the Danish Demining Group, the Norwegian Refugee Committee, the UNHCR, the ICRC, Halo — all have modern 4X4s to traverse this chaotic stretch of A9 asphalt.

We pass by white-walled compounds of various UN agencies and the Red Cross. All carry a symbol of an AK47 with a red line through it — arms prohibited on their properties.

But arms are everywhere and so is the army.

At every junction and every 150-200 metres, soldiers stand guard in sandbagged bunkers, watching carefully every car, three-wheeler, bus or motorbike driving by.

They peer carefully, some more relaxed than others, but all aware that there have been growing incidents of LTTE activity in recent months despite the war being declared officially over by Rajapakse.

As if to reinforce that, a large Tata-built armoured car whines by, honking its horn as Mohan's Austin Cambridge gives way, a soldier in goggles and hard hat in the open turret at the twin 50-calibre heavy machine guns.

A police station near Kaithady at an important junction in the road is protected by cinderblock walls covering off its windows and doors — blast proof possibly, bullet proof certainly. The officers here carry T56s too, on guard for unseen but suspected danger.

The petrol station in Kaithady has two pumps, four stray dogs and one soldier. The dogs are sleeping, so is the soldier, resting against a pole with his T56 on his lap.

Mohan pulls the Austin Cambridge up to a kerosene pump, opens the boot and fills away. He then pops the bonnet and pours cold water into the gurgling radiator. Sixteen kilometres to the gallon of kerosene, the water mileage is a bit better, I hope, if we are to make it to Kilinochchi — and back.

On the road again, we cross Kaithady Bridge, now a clanking silver bailey structure built by the Sri Lankan military, the original one having been bombed, its concrete stump foundations are all that remain. The area around the bridge is pockmarked with round craters where the bombs fell.

An army captain sitting astride a motorbike and a military police sergeant question why I am stopping at this bridge and why I am looking around at the bomb damage. They demand to see my passport and ask for the letter of permission from the Ministry of Defence Headquarters in Colombo. My papers pass muster, though they are cautious of my every move.

I make sure to move slowly, deliberately, exaggeratedly, leaving nothing open to misinterpretation by the sentries at both ends of the clanking bridge.

Driving this road is not so much a journey from one village to the next as a journey from one military unit to the next, each proudly displaying their unit, battalion and division — the 66th division, 6th Field Engineers, 18th Gajaba Regiment, 55th Division, 53rd Division, the Sri Lankan National Guard 3rd Regiment, the 55th Mechanised Infantry Brigade. Every village has a unit stationed there, mostly in the largest house, factory or school, all now billeting soldiers who are here for the long term. Even the soldiers' latrines are sandbagged, reflecting the fear that LTTE remnants might catch the military with their trousers down.

At Chavakachcheri, Mohan pulls the Austin Cambridge over to top up the gurgling radiator again and also to make way for a Hindu parade to pass — a young man hangs on hooks through his skin by way of penitence as he is suspended high above the outstretched arms of a forklift tractor.

In the background, bullet-scarred buildings are forsaken, with a few traders selling their basic wares — coconuts, vegetables, bottles of petrol — from makeshift stalls.

The welfare shop here is operated by the 53rd Division, a neat, covered shop with plastic chairs and cold bottles of water and cola. No Chavakachcherians are buying, only a smattering of off-duty soldiers from the 53rd Division sipping cola and water and tossing crumbs at a stray dog.

In places, what used to be neat, square patches of paddy fields are now abandoned to the occasional cow and calf moping through the mud. Palm trees grow towards an overcast grey sky, their trunks blackened, some split by bullet or shrapnel.

The only crop that seems to thrive here is landmines. By the thousands.

Along this stretch of the A9 south towards Kilinochchi, almost 25,000 landmines are sown — plastic anti-personnel devices that are hard to detect. There are no metal detectors used by soldiers sweeping the earth in front of them as is often seen in films. No, the work of demining is less sophisticated than that, more manual, more nerve-racking. Besides, there is no metal in landmines now — it makes them too easily detectable by soldiers sweeping the earth before them with metal detectors. Instead, the brave move forward an inch at a time, carefully checking the earth for the slightest bump, spike or trip trigger.

Out of the ground and disarmed — a relatively simple matter of twisting out the trigger and fuse mechanism — landmines look harmless, rather like a green flower pot the size of a large tin of tomatoes. Since demining operations began in earnest in the 14 months since the war's end, around 10,000 mines have been removed from the sandy earth. More importantly, the areas landmined have been clearly marked with miles of yellow plastic tape warning in Tamil, Sinhalese and English "MINES".

We stop to look and investigate. Some soldiers sit by their demining equipment, helmets and shields, mentally exhausted from their gentle probing of the soil.

I stand at the very edge of the tape, straining my eyes at every bush, bump or branch on the ground. I crouch and scan every inch of the ground beyond the yellow tape, looking for a telltale sign of an anti-personnel mine. I think I see one, its trigger spikes protruding from the ground.

I look long and hard but my eyes deceive me — it is a dead plant. Or is it? The longer I look I am convinced it is. But I will not risk life nor limb to satisfy my curiosity.

The Austin Cambridge won't start.

Am I to be stranded at the side of a minefield, not in a hostile land but in a land where hostilities are over and hosts gracious, warm and welcoming?

Mohan turns the key and the alternator whirrs. No spark is reaching the engine. We are beside a minefield. Anything can happen. Again he tries, again a whirr and nothing happens. My blood pressure is rising. He stops and thinks for a minute.

"Everything OK?" I offer nervously.

"Yes sir," he answers.

Mohan puts the engine in gear and turns the key. The car lurches forward. He takes it out of gear and turns the key. The engine kicks to life.

"Kil-in-och-chi, here I come," I start to sing in a ditty from one of those horrid musicals from Rogers and Hammerstein. Nerves have definitely gotten the better of me.

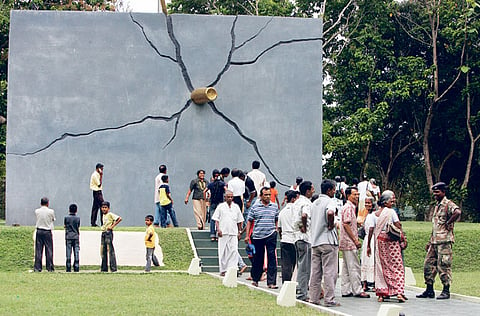

Kilinochchi was once a thriving town. Now it is not. Now it is a city of rubble, flattened buildings, toppled towers, patrolling soldiers. Now it is a city where the only obvious reconstruction is a new war memorial, opened in May by President Rajapakse to mark the first anniversary of the end of the civil war.

Two Buddhist monks chat on mobile phones as scores of visitors quietly cross a neatly sown grass park to visit the monument. Twelve sentries stand stiffly on ceremonial guard along the pathway to the monument while others discretely patrol the perimeter in camouflage, with webbing and weapons ready. There are obviously no landmines beneath this neatly trimmed grass.

Back at the mobile monument to British engineering — the 1960 Austin Cambridge — Mohan has both boot and bonnet open. And his oily canvas tool bag. "Spark plug," he says.

I watch as he takes a spare spark plug apart, using a well-worn pliers to pull out the top metal nipple, then uses that nipple to replace another in one of the four in the engine block, connecting the cables back. He smiles through crooked teeth stained from chewing paan.

"All is good, sir," Mohan assures me.

I look at the soldiers, the monument, the rubble. I think of the checkpoints, the minefields, the bomb craters, the armoured cars.

"It is for now," I answer.

"We will get back to Jaffna," Mohan says confidently.

I recall in an instant that this civil war lasted 37 years, 100,000 people died and 200,000 displaced people still remain in camps strictly controlled by Sri Lankan military and civil authorities.

"Some day," I say.

He has faith in his 1960 Austin Cambridge with the Ferrari stickers, overheating radiator and the bald tyres.

Like life in Jaffna itself, with all that is thrown at it, with all of its troubles, somehow it keeps on going.

Mohan smiles. "Yes sir. Some day."