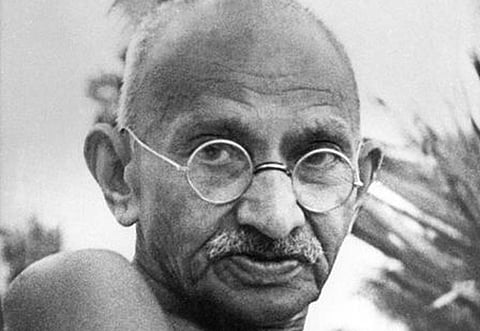

‘When I swallowed Mahatma Gandhi’s ashes’

Gulf News journalist recounts a bizzarre incident on Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary

DUBAI: As we marked the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi today, I can’t help recall a bizarre experience that dates back to my days as a journalist with The Pioneer newspaper in the late 1990s.

Following his assassination by Nathuram Godse on January 30, 1948, Gandhi was cremated with full state honours in New Delhi.

Respecting the wishes of the man revered by Indians as the apostle of non-violence and Father of the Nation, his devotees scooped his ashes from the burning funeral pyre and poured it into urns so that they could be sent across various states in the country for immersion in holy rivers as per Hindu custom.

Call it carelessness, covetousness or what you may, but by a strange turn of events, the ashes meant for the eastern Indian state of Odisha (then Orissa) were never given back to nature and somehow ended up in a bank vault in the city of Cuttack.

Apparently, they were kept aside for use in a monument, but were forgotten and remained sealed and locked in a wooden box in the bank's strong room for nearly 50 years.

After a prolonged legal battle, Gandhi’s grandson Tushar Gandhi got possession of the urn and was now on his way to the north Indian city of Allahabad to immerse the ashes in Sangam, the confluence of three of India’s’ holiest rivers — Ganges, Yamuna and the mythical Saraswati.

As a budding reporter, my job was to accompany Tushar on the 19-hour train journey and report on the historic event, which had drawn journalists from all over the world to Allahabad, once regarded as the “Oxford of the East” for its famous university.

Also on board were armed police personnel, the registrar of the Orissa High court and a senior official of the State Bank of India, in accordance with the court order.

Slogans like ‘Long Live the Mahatma’ rent the air as the train carrying the last remains of Gandhi chugged into the Allahabad railway station, its final destination, at 9.30pm — nearly two hours behind schedule on January 29, 1997.

I watched in awe as thousands of Gandhi supporters gathered at the railway station jostled with each other to catch a glimpse of the red wooden box containing the ashes.

Around midnight, the box was transported by a police convoy to a nearby government guesthouse, where musicians and preachers of different faiths — including Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Christians — sang hymns that were once sung by Gandhi.

Huge crowds thronged the place the following morning as people from various corners of the city turned up to pay their tributes to the great leader.

Later that afternoon, we boarded a motorboat to reach a wooden platform specially erected for the media in the middle of the river. Bang opposite us was another, much bigger stage carrying Tushar, several Hindu priests and scores of dignitaries including, if memory serves me right, the then Uttar Pradesh governor Romesh Bhandari, federal ministers Chaturanan Mishra and Jnaneshwar Mishra.

Barely a few metres separated the two stages. At the anointed hour, Tushar, his wife Sonal and two children stood up with the blackened copper urn that had remained sealed since 1948.

It was the moment we had been waiting for. As we stiffened to attention and the photographers readied their cameras, Tushar opened the urn amid chanting of shlokas from the Vedas and other Hindu scriptures. Just then, a gale of wind swept across the river and Gandhi’s ashes flew right in our faces.

I was standing in front and remember swallowing a fair bit of it. As I doubled over coughing, a visiting foreign journalist remarked jestfully: “Mate, you just tasted Gandhi.”