Empowering rural women

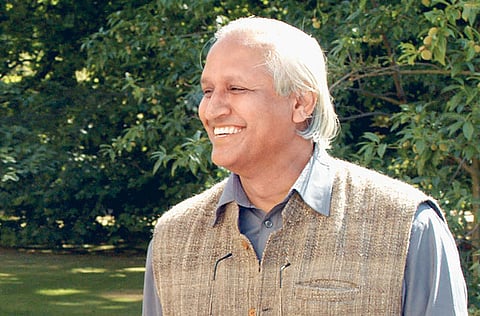

Dr Bunker Roy feels solar technology can help change lives in impoverished villages

Dr Bunker Roy found his calling while detonating explosives in an open well at a village in India. His time with the residents who call the back of beyond home cemented his dream of using traditional expertise rather than "bookish knowledge" for the uplift of neglected communities. Nearly four decades and an award later, Dr Roy speaks about the philosophy that transformed a vision into the Barefoot College.

What is the philosophy that drives Barefoot College?

Our primary aim is to demystify education. Mahatma Gandhi believed this was essential for the development of India and his thoughts have been adapted to the work-style of our college. Living conditions for everyone here are simple and down-to-earth. Everyone sits and works on the floor. Everyone takes a living wage and not a market wage. The highest salary one can get is $100 per month.

Our second mission is to make the young rural men, women and children stay in their own villages and better its environment rather than migrate to cities and end up in slums.

Third, we try and build the confidence and competence of these ordinary people — the Barefoot technologists, as we call them — by training them to become self-reliant. We need to identify and apply informal educational (as against "literacy") processes so that they can understand, respect and apply technologies that can meet their basic needs such as drinking water, health, lighting, night schools, employment and housing.

You established the college back in 1972. Do you think it has measured up to your vision since then?

After college, for five years (1967-1971) I did nothing but deepen and blast open wells for water. I lived with the poor under the stars and heard the stories they had to tell of their skills and knowledge that books, lectures or university education can never impart. My real education started then, when I saw water diviners, traditional bonesetters and midwives at work. That was the humble beginning of Barefoot College and my vision, as it were.

You lay emphasis on women's empowerment.

The college believes that the poor have every right to control, manage and own the most sophisticated technologies to better their lives. Just because they cannot read and write is no reason why they cannot be water and solar engineers, designers, communicators, midwives, architects and rural social entrepreneurs.

It is now our policy to train only illiterate/semi-literate middle-aged mothers and grandmothers from villages all over the world. The concentration since 2004 has been on training women from Africa.

For women who have rarely left their village, it requires lots of courage and patience to leave their homes and families for six months of training to come to India. The presence of so many nationalities creates a dynamic environment of cultural diversity but raises concerns over language and communication.

The need for expression gave birth to the unique Barefoot language — a combination of gestures, signs and broken English which transcends language barriers.

But what is extraordinary is the involvement of rural women in the dissemination of sophisticated technology. For the first time, solar technology has been demystified and ordinary village women from nine states have demonstrated how effectively they can manage and control technology to improve their quality of life.

You don't issue any certificates at the end of any training. Is that deliberate?

Issuing certificates by training institutions is one of the reasons for migration from the villages to the cities. Once they have a certificate in their hands, within 24 hours they're off to get a job in the city!

Our target constituency has been the rural poor families living on less than a dollar a day. The women who are spending hours fetching kerosene, wood, candles and torch batteries for lighting at very high costs. After food, their highest expenditure is on lighting. They have to travel vast distances on foot for ten litres of kerosene that they can barely afford. They have to walk miles for firewood from an already vanishing forest area all over Africa.

The programme helped us break several myths associated with solar technology and learning.

It proved that it does not require "paper qualified" persons to become solar engineers. A woman Barefoot solar engineer with less than ten years of schooling can instal and maintain modules that produce 45 kilowatts of electricity on our campus and teach solar electrification to women like themselves in their countries.

The Barefoot approach is serving poor communities in 21 African countries identified as the Least Developed Countries in the UNDP Human Development Report.

As a result of their collective efforts, these women have managed to save 30,000 litres of kerosene per month from polluting the atmosphere all over Africa. They are the hardest hit from the fuel and energy crisis but they have set an example. Drudgery has been reduced. They are empowered to raise their self-esteem and community respect.

The local people trained by you must be feeling the pull of greater cities. How do you contain that migration?

Barefoot College has shown what is possible if the very poor are allowed to develop and organise things. Ordinary people get written off by society because they are labelled as poor, primitive, backward and impoverished. Over the past 38 years, several thousand poor young unemployed and unemployable rural youth, both men and women, have been trained as Barefoot professionals. The rural youth selected by the community have to be impoverished, subsisting on barely one meal a day. The idea is that once they are trained (as slowly as they can absorb), they will never leave their village or community because no government or private agency will ever employ them.

How tough is the challenge of running a unique organisation such as the Barefoot College?

For the past 38 years, the long-term mission of the Barefoot College has been to work with the marginalised, the exploited and the impoverished. The dream was to establish the first and only rural college in India built by the poor and exclusively for the poor. Living conditions are simple so that the poor feel comfortable. There is a spiritual dimension in the college, because working relationships depend totally on mutual trust, tolerance, patience, compassion, equality and generosity. The idea is to apply the knowledge and skills the poor, the deprived, the neglected, the semi-literate and the impoverished rural poor already possess for their own development, thus making them independent.

What do you think needs to be done by the Indian government to make the environment more enabling for enterprises such as yours?

Between 2004 and 2009, the Barefoot approach of training illiterate rural women to solar electrify their villages was extended to Africa. By this year, more than 100 semi-literate and illiterate grandmothers from 21 countries in Africa will have solar electrified their own villages. Under a unique scheme called ITEC, the Indian government has covered the air tickets and six months' training costs to each of these grandmothers to come to India.

What the Barefoot College has effectively demonstrated is how sustainable the combination of traditional knowledge and demystified modern skills can be when the tools are in the hands of the rural poor. Our message has reached the far corners of the globe. The respect our community has for the Sun (solar electrification) is really a simple message which is easily replicable in inaccessible, neglected and backward communities all over the world.

Neeta Lal is a journalist based in New Delhi, India.