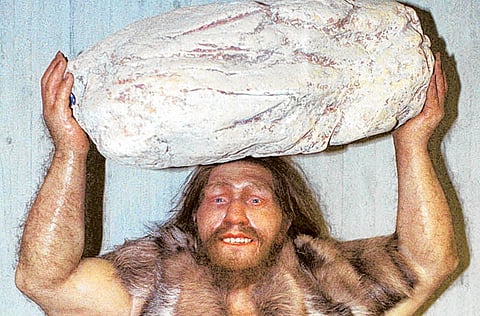

We’re still part knuckle-draggers

Neanderthal genes helped modern humans evolve, studies suggest

Los Angeles: Mating between Neanderthals and the ancestors of Europeans and East Asians gave our forebears important evolutionary advantages but may have created a lot of sterile males, wiping out much of that primitive DNA, new genetic studies suggest.

The comparison of Neanderthal and modern human genomes, published online Wednesday in the journals Nature and Science, identified specific sequences of altered DNA that both Neanderthals and several hundred modern Europeans and Asians had in common.

Those stretches of common heritage offer intriguing hints at what borrowed code helped modern humans adapt, and what was eliminated.

The strongest remnant of our Neanderthal heritage appears to be centred around as-yet unknown changes in skin and hair that likely proved advantageous, the two studies suggest.

“The group of genes that stand out are genes that code for things in the skin, particularly keratin, which is a structural component of skin, and another group of genes that are keratins in the hair also pops up,” said geneticist Svante Paabo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, one of the authors of the research published online Wednesday in the journal Nature. “So it suggests that something came over from Neanderthals to present-day people that had to do with the skin and was advantageous and rose to high frequency.”

The two studies add detail to a growing consensus that modern human ancestors did more than bump elbows and eventually replace the Neanderthals that preceded them out of Africa. They mated with them around 50,000 years ago — a series of as many as 300 encounters that has left a 1 per cent to 3 per cent Neanderthal footprint on the genome of anatomically modern Europeans and Asians, the researchers said.

“Individually, we are a little bit Neanderthal,” said Joshua M. Akey, a population geneticist from the University of Washington, and lead author of the study published in Science. “Collectively, there is a substantial part of the Neanderthal genome that’s still floating around in the human population that’s just shattered into different pieces, and everyone has slightly different parts.”

The reports build on the publication in December of the full genome of Neanderthals that showed that they were genetically closer to modern Europeans and Asians than to modern Africans. The best explanation for that phenomenon was gene flow — a fancy term for interbreeding between the divergent species, which shared a common ancestor some 300,000 to 500,000 years ago.

At least 20 per cent of the Neanderthal genome “introgressed” into the genome of our European and Asian ancestors, and East Asians retained slightly more of it, according to Akey’s analysis, based on genomes from 379 Europeans and 286 East Asians.

The slightly larger Neanderthal footprint among East Asians is not easily explained without a second “pulse” of gene transfer after they parted from Europeans, Akey’s study suggests. “It’s a two-night-stand theory now,” Akey said.

As few as 300 matings could have inserted the Neanderthal heritage in the genome of the common ancestors of Europeans and East Asians, Akey estimated, though he cautioned that there was a lot of uncertainty surrounding such an estimate.

“Those 300 matings could happen in a single generation; they could be spread out over 10 generations. We can’t distinguish,” Akey said.

So where did all the Neanderthal genetic code go? Much of it went to the grave with sterile males, who carried it on their single X chromosome, said Paabo. “Males have only one X chromosome, so if they get a slightly bad version of this from Neanderthals, they have no other version of the X chromosome to compensate with,” he said.

Without strong selection pressures, the Neanderthal portion of the modern European and East Asian genome could have been twice as large as is evident now, said Paabo’s co-author, Sriram Sankararaman, a statistical geneticist at Harvard Medical School who analysed more than 1,000 European and Asian genomes.

“The 2 per cent we see today is what’s remaining after there’s been some purging,” Sankararaman said. “We think that it was reduced by about a third.” That purge of Neanderthal DNA is “a huge amount in a relatively short period of time,” he said.

The Neanderthal genome project has made large advances in the past several years in the understanding or our closest human relatives, who vanished about 28,000 years ago.

Short-bodied and brutishly strong, with oval skulls featuring pronounced brows and nasal cavities, the Neanderthals were well adapted for colder climates, using flaked tools, and hunting to supplement forage unavailable in colder months.

For decades, paleontologists and geneticists found little evidence of interbreeding, but as methods and tools improved, evidence began to accrue in both the fossil record and genetic analyses.

The first draft of a full Neanderthal genome, published in 2010 by researchers at the Max Planck Institute, was followed last year by a far more detailed description of the genome using samples from multiple Neanderthal fossils. More recent work in December established that Neanderthals were more related to Europeans and East Asians than to modern Africans, suggesting gene flow between them. Analysis revealed that about 1 per cent to 3 per cent of the non-African genome could be attributed to Neanderthals, with East Asians having a slightly larger share than that of Europeans.

“It was established a couple years ago that there was a small but significant admixture with Neanderthals, but that doesn’t mean that the genes that were brought into modern humans had any function, that they were an improvement on what modern humans had,” said Montgomery Slatkin, a UC Berkeley biologist who has done similar research on Neanderthal genetics but was not involved in either study. “But now there is convincing evidence that indeed some of them at least were selected in humans.”

Genes linked to several modern diseases were among the Neanderthal legacy, including those correlated to Type 2 diabetes. But how much of a risk we inherited is debatable — the diabetes gene likely helped us survive food shortages, and may have proved detrimental as food became all too abundant in recent time.

Other studies have traced important immune system genes to Neanderthals and another extinct group, the Denisovans.

While both studies highlight the DNA that anatomically modern humans have in common with an extinct species, ultimately researchers are more interested in what makes us modern humans.

“That’s what really burningly interests me in the coming years,” Paabo said.

“Our genomes are kind of this new territory for excavating the remains of unknown hominins,” Akey said. “I’m pretty confident that we’ll be able to find new twigs on the family tree.”

In the meantime, we may want to give Neanderthals their due, Paabo suggested.

“They are not sort of fully extinct, if you will,” he said. “They live on in some of us today — a little bit.”