It’s been over a decade since Irish expat Niamh Graham was in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in the UAE, staring at her baby. Recalling the sight of the newborn riddled with needle marks and hooked up to beeping monitors, an emotional Graham calls Grace her ‘miracle baby’.

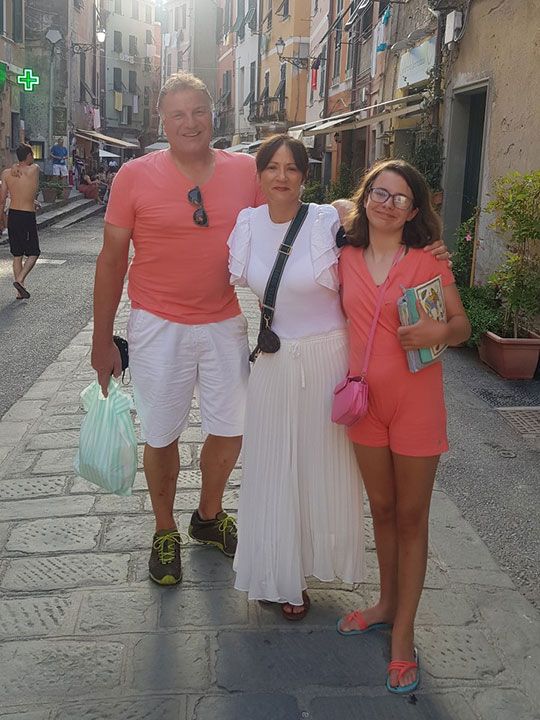

Grace, who is 12 years old and has just moved with her family back to Ireland, still has battle scars from her time in the NICU, when she fought to stay alive.

Graham recalls that she knew the pregnancy wasn’t going to be easy – she had been trying to conceive for a number of years and had even had a miscarriage before there was a flutter of life.

Graham recalls: “At 23 weeks, I went to my gynaecologist to have a scan, just to make sure everything was okay. My gynaecologist had retired at the time and there was a new male doctor on call. He was quite matter-of-fact. I asked him if I could exercise and he said that was fine.”

Fast-forward two weeks and after a gentle walk, Graham felt something was amiss. By 6pm, Graham was calling her husband, panic in her voice. “I rang my husband who was on his way home from work. I said, ‘Look, get home quickly’, I’m having a bleed, we need to go to the hospital. So we got to the hospital and immediately they took me into the emergency room and they hooked me up to a monitor to check the baby’s heartbeat. Thankfully, she had a heartbeat but I did have bleeding in the birth canal,” she says. The baby was alive, but in critical condition, and Graham had to be pumped with steroids and magnesium to aid development.

“The next morning they took me in a wheelchair for a scan and during the scan, the doctor said to me, ‘Oh, you are dilated’. And I was like, how dilated, because of course I’m only 25 weeks. And she said, ‘Very. You’ve come up on a wheelchair, you’ll be going down in a stretcher.’ So I went down to the room in a stretcher,” she recalls, her voice shaking with grief.

“The gynaecologist, whom I had only met once, came into the room and did an internal examination and said – I’ll never ever forget this for as long as I live – he said to me, ‘Not to worry, you can have more children.’ He gave her no chance.”

“He said, ‘Your baby is breech, she had to be delivered, it has to be now and it has to be emergency Caesarean.’ He said, ‘We are taking you into surgery.’

“I thought from then on that she was dead.”

When it came time for a numbing jab – the anaesthetist was worried; the stress and fear had caused Graham’s blood pressure to shoot up and in that state, she could not be given the medication. It took the anaesthetist a while to calm Graham down enough to be medicated. When Grace was born, Graham was given her little baby. “I felt like they were giving her to me to kiss her goodbye, so I kissed her face and they took her away. I thought I wouldn’t never see her again. The next thing, I wake up in recovery and I couldn’t go visit because I’ve had a C-section, but my husband had been in there and he showed me the photographs. She was in this tray, covered in cling film, because they need to keep the heat in. They had a blue light on and an ultraviolet light on to help with the development and to me, she looked like an alien – she didn’t look like a baby at all.”

List of things that could go wrong

This 800-gram baby had a distended stomach, and she was attached to a various tubes and a high frequency ventilator that shook her from head to tiny toe. “I remember the nurse gave me a list of things that could go wrong with premature babies – just so we were prepared for all eventualities - and of the 32 things on that list, Grace ended up getting 28. We were in NICU for almost six months,” she says.

Twelve days into living, baby Grace was operated on; they couldn’t find a reason for the swelling in the stomach, but they put a drain on either side. Two weeks on, the abdomen was cut open again to remove the intestines and check for whatever was causing the inflammation. “They had to take her intestines out on to the table to find out what was wrong and they found there was 10cm rotten of her bowel and so they had to cut out the 10cm and put it back in. And it’s because all the while she hadn’t been able to go to the toilet, she hadn’t been able to poo and she was on total parenteral nutrition (TPN) – food by drip – she still has pin prick scars on her hands from all the needles, even 12 years later,” recalls the mum.

During her third operation, an Ileostomy was conducted, and Grace’s heart stopped on the operating table. “We met the anaesthetist coming out of the operation and we were like, oh, how was the operation? She didn’t know she was talking to the parents of the baby she’d just been in with – and she said, ‘Oh, the baby’s heart stopped on the operating table’. And we said, oh that’s our baby – and she went pale.”

The touch-and-go moments were not over yet. “Then she had a bleed in the brain. Thankfully, the bleed dissipated by itself. Then she had a broken arm, she had laser surgery in both her eyes – premature babies often get retinopathy of prematurity, where the vessels go grow too far back in the eye and they have to laser them or they go blind. She had a fungal infection that put her 48 hours in isolation. She had two other infections that put her into isolation. She had about three blood transfusions, and she had so many needles in the head that eventually they gave her a line through her neck, so she has a big scar to this day on her neck,” says Graham.

Finally, when Grace seemed to be getting better, drinking breast milk, and almost ready to go home, Grace developed Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) – in which intestines get inflamed and the tissue dies. This condition is often fatal to preemies.

Treatment depends on the stage of NEC but mainly, the feeds are stopped and antibiotics are given to fight infection. Sometimes, the infected intestines may need to be removed.”

She was put on TPN for three weeks. “When I got the news that she had NEC - I had read previously that babies could die from it – that day I had a mini breakdown, I couldn’t breathe. I was breathing into a brown paper bag and they had to give me oxygen. There were lots of moments where I’d get upset because of bad news – because for every two steps forward we were taking two steps back. But this was … just when we thought not long now, we are almost out of the door – that’s when she got this,” she says.

An emotional rollercoaster

“It was another few weeks where we had to wait for that to heal. We became friends with everyone in there – it was the worst of places but it was the best of places because we saw babies dying but we also saw babies leaving. And you go through so many emotions – guilt for being there, jealousy when you see babies leave; grief for parents losing their baby,” she says.

“I don’t know how my marriage survived this, but it did. My husband was a rock – he said to me, because I was kind of glass half empty – I just thought she was going to die after every operation – ‘We’ve got to believe in Grace. She will pull through this’. She came out of her second operation with her fist in the air and he said to me, that’s what we’ve got to have faith in; she’s a fighter.”

Graham says that six months on when Grace beat the odds and got home, she found herself suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. “Certain triggers - I used to play the iPod to her in the incubator and if a song came on in the car I could just break down in tears. Or a smell. I used to wear a perfume and I couldn’t wear it for a long time afterwards because the smell reminded me of the hospital. I would have regular moments of just sitting in the car and crying.”

When Grace got home, the Grahams were scared of apnoea – a condition where a person’s breathing suddenly stops - because that had happened to the infant in the NICU. “We had to tickle her foot and remind her to breathe,” recalls Graham. Fortunately, she adds, “My friend got this device that [latches onto] the nappy and if she stopped breathing for a moment, it would vibrate and remind her to breathe – that gave us a great deal of comfort knowing that we had that. But we had to be careful about bathing her when we got home because her tummy was very bloated.

Grace survived – and is thriving 12 years on, but that’s not to say her stint in the NICU didn’t have consequences. “Developmentally, she was tiny bit delayed – I wouldn’t say too delayed but her fine and motor skills were not the best – even to this day, doing her buttons and tying her hair really get her frustrated. But mentally, thankfully, everything was fine – she was reading books at three and four years of age. She is 12 but currently she has a reading age of 15-16. So she’s quite bright but the only effects that I would say she had afterwards besides the scars were the growth and motor skills. But we were quite lucky,” she adds.

Other than a couple of ailments such as fever over the years, Grace hasn’t needed medical intervention, her mum says. “I don’t know how she’s alive. It’s a miracle,” she adds.

Share your story with us at parenting@gulfnews.com