Rousseff tone-deaf to Brazil’s seething streets

Rousseff can do more to put Brazilians at ease

The best news from the anti-government demonstrations that put as many as two million people in the Brazilian streets last Sunday is that Latin America’s largest democracy is thriving. In contrast to the seething protests of 2013, the marchers were angry, but not violent, the police response was measured, and the demonstrations ended in beer and song, not pepper spray and arraignments.

The official response to the popular outpouring was less encouraging. In an attempt to tap the zeitgeist, Brazilian Justice Minister Jose Eduardo Cardozo and presidential general secretary Miguel Rossetto convened reporters to tout the protests as proof that the government abides democracy, was attentive to the pulse of the streets and even then was preparing a new anti-corruption offensive.

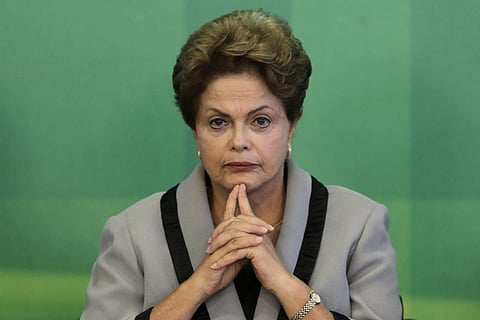

The message might have come through clearer if President Dilma Rousseff had delivered it herself. Or if the promise of new anti-corruption policy was not recycled from last year’s campaign, and a landmark bill to stamp out bent business practices was not still languishing on Rousseff’s desk. No wonder her lieutenants were hard to hear over the pot-banging and honking that contrarians staged in many cities during the televised press conference.

“The government has an obligation to open a dialogue, with humility,” Rousseff told reporters on Monday. Far more convincing than the administration’s attempted public relations stunt was the arrest on Monday morning of Renato Duque, a former executive at the state oil giant Petrobras, and one of several dozen officials targeted for investigation in a scandal that prosecutors say involved at least 2.1 billion reais(around Dh2.87 billion) in kickbacks and bribes used to fuel campaign slush funds. Also indicted was Joao Vaccari Neto, treasurer of Rousseff’s Workers’ Party, for allegedly disguising bribes as campaign contributions. But those moves were made by prosecutors and the federal police, not the administration.

Last Sunday’s orderly outpouring was in many ways a fitting tribute to the 30th anniversary of the end of military rule. True, those hoisting “SOS Armed Forces” signs seemed to have forgotten their history. Still, most confined their demands to fixing democracy, not junking it. “Congratulations for your courage, Sergio Moro,” read many placards, in a nod to the federal judge behind the Petrobras probe.

Such sentiment must be little comfort to the Workers’ Party, which was forged 35 years ago from massive strikes and street protests and now has gone from “rock to window pane”, as the Brazilians put it The most popular T-shirt on parade last Sunday bore an oily handprint with the little finger missing — a visual send-up of former president Luiz Inacio “Lula” da Silva, who had lost a finger to a factory accident and later lost his self-control over Petrobras.

But Rousseff, who served as Lula’s chief-of-staff and chaired Petrobras for most of the Lula era, is the one mainly getting smeared on the streets. One reason is Brazil’s sharp economic contraction. There is also trench warfare with congress, where opposition lawmakers and dissident allies have mutinied over the austerity measures and taxes that Brazil needs to fix its budget deficit and woo investors.

Rousseff can do more to put Brazilians at ease than claim that democracy is working, better times will come and the government is open to dialogue. Writing the enabling laws for the 2013 anti-corruption bill and signing it into law would be a start. She also might set up the long-promised secretariat for oversight of state companies. “All the recent corruption scandals started in state companies, where there is little transparency and almost no accountability,” Gil Castello Branco, head of the watchdog group Contas Abertas, told me. Even Rousseff’s toughest critics could get behind the idea of fixing that.

— Washington Post