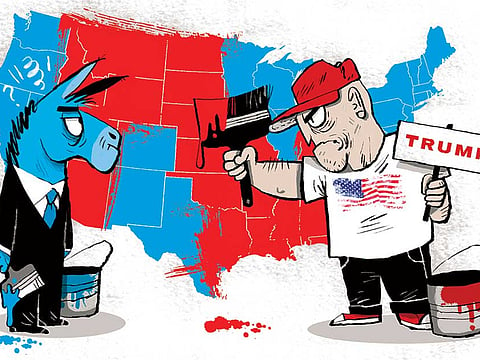

Why Trump stays afloat

The same forces that propel a radical candidate to a party’s nomination also provide a floor through which he is unlikely to fall

In one of the most emotionally wrenching presidential races in living memory, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump’s support is as level as a pond. In polls, it is holding steady around 41 per cent, right where it was after the first debate in late September. This plateau has persisted through the second and third debates with his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton, and the revelation of his recorded boasts of sexual assault. Even the stunning public rebuke of Trump by the parents of Iraq War hero Captain Humayun Khan in late July was followed by a swing of just a few percentage points, quite small by historical standards. Why has Trump’s support not collapsed further in the face of some fairly damning revelations?

Such high stability in polls is not new. It started several decades ago. One measure of the stasis of modern campaigns is how much each party’s support in polls changes over the course of a campaign. From 1952 to 1992, the average range — the difference between maximum and minimum levels of support — was 17 percentage points. Since 1996, the range has dropped to 8 points. Trump’s range is 4 points, from 39 to 43 per cent.

At his lowest point, Trump still had more support than George McGovern, who got the smallest percentage of the popular vote by a major party candidate in the postwar era in 1972, with 38 per cent. Clinton’s average margin over Trump of 5 points has been enough to make her the first candidate to maintain a durable lead in an open presidential race since Dwight D. Eisenhower defeated Adlai Stevenson in 1952. So the bigger question is not about Trump, but why the last six presidential campaigns became so stable.

The answer is polarisation. The same forces that propel a radical candidate to a party’s nomination also provide a floor through which he is unlikely to fall. Trump’s ascent is the culmination of trends that began in the 1990s, when Newt Gingrich introduced the Contract With America and adopted tactics like government shutdowns and impeachment. More than any national figure since Sarah Palin, Trump embodies these attitudes.

The founders thought that a physically far-flung republic would avoid such “mischiefs of faction.” In The Federalist No 10, James Madison suggested that the slowness of communication between distant states would prevent the formation of organised factions inflamed “with mutual animosity.” But modern communication has rendered Madison’s point of view obsolete. At the same time that voting patterns stabilised in the 1990s, instant long-distance communication allowed the coordination of message and ideology across long distances — and Republicans are more likely to be found in sparsely populated areas.Madison thought that even if a faction shared common motives, physical distance would make it difficult “to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.”

The dangers of wrong information

Partisan media is not new, of course — in the 1800s, the chief funding for newspapers came from political parties — but talk radio, Fox News and Breitbart can reach like-minded voters with tremendous speed. Social media intensifies the segregation of voters by providing channels of communication tailored to specific preferences. When cable news organisations often seem unwilling to call out falsehoods, wrong information can cause tremendous damage. Technology has made Madison’s vast republic virtually small.

Communication goes two ways, and Trump takes this to an extreme. A reality TV star and a leader in the birther movement, he quickly became the first choice of a plurality of Republican voters from the start of his candidacy in 2015. He is adept at using Twitter to send messages to his nearly 13 million followers.

Trump’s success with Republican voters at odds with the party establishment can be explained by the fact that he is one of them, raised up to be their nominee. They will not abandon him, any more than they would abandon themselves.

Voter entrenchment is maintained in part by negative feelings about the opposition. Such warfare takes a toll. The approval ratings of both major nominees have declined steadily over the last 20 years, and Trump is the most negatively viewed nominee that Gallup has ever recorded. Democratic-leaning voters and many college-educated Republicans find it unthinkable to support Trump given his appeals to racial and anti-immigrant resentment. In 2012, Mitt Romney came with the baggage of his party; in 2016, Trump is baggage personified.

For this reason, Clinton’s support is unlikely to flag even as her email has again attracted the attention of the FBI. Likewise, for committed Republicans, support for Clinton is out of the question. In a Florida survey, 84 per cent of Trump voters said that Clinton should be in prison, and 40 per cent said she was a demon.

With polarisation, many voters’ preferences have become predictable from their social and cultural characteristics. Even so-called undecided voters are more decided than they realise. It has been suggested that the Republican Party is motivated today not by political conservatism, but a reaction against contemporary life. Trump voters resemble Romney and John McCain voters. They are whites who are more likely to be evangelicals who did not graduate from college. Tensions between these groups and elites and minorities limits the range of support that either side’s candidate will receive. Partisan geography has become more fixed, too. In terms of patterns of relative strength and weakness, the electoral map is more stable than it has been in 50 years. For this reason, talk of Clinton’s winning Texas is overblown. If that happens, I promise to eat a bug.

Trump’s candidacy has revolved almost entirely around emotionally powerful issues like race, immigration and anti-Muslim sentiment. The more you feel a decision in your gut, the less likely it is that you will change your mind. White nationalists think white nationalism is great, but others are repelled. And in a Raycom/Mason-Dixon poll of the Louisiana Senate race, supporters of white supremacist David Duke favoured Trump over Clinton 81 per cent to 6 per cent.

Voter polarisation translates easily to extreme legislative bodies. In any district dominated by one party, representatives are determined mainly in primary elections, when turnout is low and the most likely voters are motivated partisans, fulfilling Madison’s fear that “a common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority.” By numerical measures of ideological intensity, from the 1970s to the 1990s, centrism steadily disappeared from the House Republican caucus. Single-party domination has expanded since 2012 because of increased partisan gerrymandering, which eliminated dozens of competitive districts. These trends suggest that partisan gridlock will continue long after Election Day.

Although technology has contributed to polarisation, it may also help rescue us. For example, Facebook has automated story selection for its custom news feed; for political news this tends to foster an echo-chamber effect. However, Facebook data scientists have found a better source of diversity: almost 30 per cent of hard-news reports originating from friends reflect opposing views. Even better, individuals are likelier to engage with information like this when it is presented in a social context.

For now, we are stuck with an intensely emotional campaign that has been a significant source of stress for more than half of adults. The American Psychological Association has, for the first time, issued tips on dealing with election-related stress. Strong emotional experience reduces mental flexibility, suggesting that when tempers run high, as they have for many voters this season, entrenched support for a party or candidate is more likely. So if you wonder whether there is anyone left to persuade, the answer is probably no. We’re too freaked out.

— New York Times News Service

Sam Wang is a professor of neuroscience and molecular biology at Princeton University and a founder of the Princeton Election.