Why nostalgia is not always a good idea

As a political ideology wistfulness can sometimes lead to blunders and spread of racism

The ancient Greeks considered nostalgia a sickness, some sort of a medical condition akin to anxiety. The term comes from two Greek words: ‘nostos’ which means ‘coming home’ and ‘algos’ meaning ‘pain’. It referred then to the notion of feeling homesick, which has since become part of the English language.

In modern times, however, sociologists altered the term to refer to a more romantic feeling of ‘the good old days’, or one’s happy early years. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, nostalgia means “a feeling of pleasure and also slight sadness when you think about things that happened in the past.”

Most of us have experienced that when watching an old movie, a black and white classic, or listening to an old song that triggers a long-lost memory. That is nostalgia. Some feel nostalgic when trying to connect with a childhood friend, someone they haven’t seen for many years. Mostly, it isn’t about the friends they seek but the happy times they felt at that age.

'Good old things'

I sometimes find myself searching for an old movie or a play on YouTube. I do that a lot lately. I also find it exciting when my children ask me about the old Ramadan customs — I can’t get myself to stop from talking about our old neighbourhood, the people, the nightly gatherings, and all the ‘good old things’ that seem to have vanished in these fast-changing times.

A little of nostalgia, from time to time, doesn’t hurt. It may even be useful. Those nostalgic moments help us to put things in perspective, to realise where we come from and appreciate our past and learn from its mistakes. But I think too much of nostalgia is bad, a sickness.

It is like a hamburger meal. We like it once in a while. Some call it ‘cheat day’, interrupting their strict diet regime. However, too many hamburgers is a recipe for a health disaster. So is nostalgia. Too much of it is a clear sign that someone has lost touch with reality, especially when it is mixed with politics. That is definitely a recipe for social disaster and a sign of a decaying society that has nothing to offer anymore.

Build the future

Some societies seem to indulge in nostalgia, especially the ones where populist movements are on the rise. “Let the dead bury the dead,” says Karl Marx. Don’t be dead among the living; don’t live in the past. Take advantage of its experiences to fix the present and build the future.

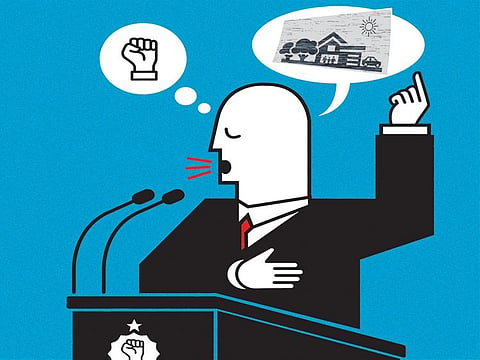

Populists use selective communal nostalgia to score political goals. ‘Make America Great Again’, President Donald Trump’s rallying slogan for the past five years is a prime example of provoking nostalgic sentiments among white Americans, some of whom long for the ‘good old days’ when America was mostly white and Christian — well before the onslaught of the immigrants who took their jobs, changed the prevailing Anglo Saxon culture and dared to speak their own language in their homes!

Nigel Farage and his group of Eurosceptics in the UK Independence Party exploited the same nostalgic sentiment to push for Brexit, which many British now feel was a historic mistake, a modern-day first-degree political blunder. Nostalgia was a key reason of the Leave vote, a recent study by University of Oxford found out. Brexit voters felt cheated by globalisation, immigration policies, and ethnic diversity. They decided to make England great again, I guess.

Diplomatic crises

Other forms of political nostalgia may even cause diplomatic crises such as the one that took place over the weekend between Iran and Turkey, two regional players indulging in national nostalgia aimed at reviving their old glory.

Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan is well known to be an advocate of restoring the ‘glory of the Ottoman Empire’ while Iran longs for the times when it had virtual hegemony in the Middle East. They both refuse to recognise the present and use all means necessary to realise those impossible dreams. They even became accidental allies as they both support the same extremist proxy militias, which have been wreaking havoc in several Arab countries.

On Friday, Iran’s Foreign Ministry summoned the Turkish ambassador to protest Erdogan’s recitation of a controversial poem during his Thursday visit to Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. The poem, according to Iranian officials, implies that two Iranian northern provinces that are populated mostly by ethnic Azeris were historically part of the neighbouring Republic of Azerbaijan.

The poem refers to the Aras River that separates Iran and Azerbaijan since the 19th century when that country was divided between Russia and Iran. Erdogan seemed to call for the return of those provinces to Azerbaijan. Tehran says his remarks are “interventionist and unacceptable”.

A spokesman of the Iranian ministry of foreign affairs said: “The Turkish ambassador was informed that the era of territorial claims and warmongering and expansionist empires was over.” One can safely say that about Iran too. Both countries are always cited as examples of historical nostalgia, the disastrous type for sure.

Racists in disguise

Nostalgia as an individual sentiment is fine, from time to time. But when it becomes an electoral programme or a political ideology of a ruling party, then the ancient Greeks were right — it is a sickness.

A social disease, especially when the majority in a society indulge in the extreme type of this sentiment to persecute the minority because they look, speak, dress or eat differently. Populists who exploit those sentiments are racists in disguise. They are too cowardly however to admit their contempt for those who don’t look like them.