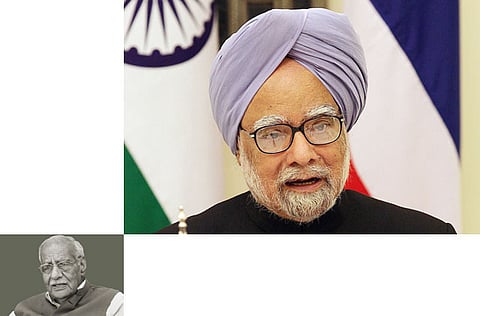

Who's next after Manmohan Singh?

What ails the Congress is that it has very few leaders who are of prime ministerial stock and Rahul Gandhi has not revived the Nehru-Gandhi charisma

After Manmohan Singh who? The political parties and the people are prying into the affairs of the ruling Congress to make a guess. It is not that the Indian prime minister is indispensable. Nor has he been out of step with the pace of Congress president Sonia Gandhi, the real power. It is merely her calculation when to anoint her son, Rahul Gandhi.

True, lately Singh's stock has plummeted and even as an economist he has been found out of depth. But these are only aggravating factors. The real reason is Rahul Gandhi, who unfortunately has not revived the Nehru-Gandhi charisma. One question before Sonia is that the President of India, Pratibha Singh Patel, retires in the middle of next year. Should Singh be elevated then? Even otherwise, Singh will be almost 80 years old in 2014 when the new Lok Sabha is elected.

What ails the Congress is that it has very few leaders who are of prime ministerial stock. Names of Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee, Defence Minister A.K. Antony and Home Minister P. Chidambaram come straight to one's mind. Yet all the three do not make the top position for one reason or the other. At least, Mukherjee and Chidambaram are not in the reckoning of Sonia whose say is beyond doubt.

Antony may be her choice if she ever decides not to put her son in the Prime Minister's chair. No doubt, Antony is honest, humble and measures his words before uttering them. But he has not yet attained the stature of an all-India leader, particularly in the Hindi-speaking states. Mukherjee is the best troubleshooter the Congress has and he has been entrusted with some thorny problems which he has sorted out. Yet he is not considered trustworthy by the dynasty which lost confidence in him when he threw in his hat for the prime ministership after the assassination of Indira Gandhi.

Feud in the party

Singh who has matured politically in the seven and a half years of prime ministership knows about crisscrossing and dissensions in his party. Sonia has been his great teacher and he has learnt from her when to tick off whom. Before going abroad this time, the prime minister had the cabinet secretariat to issue a communique to make it clear that there was no No. 2 in the government. Singh himself remained in control even when he was out of the country. However during his absence, either the home minister or the finance minister can preside over the cabinet committee on political affairs.

Apparently, their feud was in the prime minister's mind and he therefore, did not nominate either of them as ‘No. 2.' However, Mukherjee will preside when there is a meeting of the cabinet committee. Chidambaram gets the chance if and when Mukherjee is not available.

Understandably, Antony does not figure in the communique. I have a feeling that both Mukherjee and Chidambaram may be ignored and Antony can be the dark horse. But this depends on whether Rahul can still make waves. UP can be his waterloo.

Senior most Agricultural Minister Sharad Pawar who has expressed his frustration may have been in the reckoning if he had stayed with the Congress. But he left it to protest against a foreigner, the Italian-born Sonia, becoming the party president. How can she tolerate him occupying the top position?

Many years ago, the Congress faced a similar problem on the selection of successor when then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru fell sick a few months before his death. Yet the challenges were different at that time. There was no dearth of leaders. Lal Bahadur Shastri, Morarji Desai, Jagjivan Ram and Nehru's own daughter, Indira Gandhi, were popular among the public.

The real challenge, which the western media had hyped, was whether the democratic system in the country would stay after Nehru. Journalists from the UK and the US, particularly from the former, predicted that democracy would end once Nehru breathed his last. The West never understood that the diversity in India would not allow any system other than democracy to stay. The problem which faces India is trivialisation of the society. Elections have refurbished the sectarian caste or even sub-caste. Even religion has begun to play some role. Nehru at one time got the columns of caste and religion in application forms to government jobs or admissions to schools deleted. Singh's success could be in unleashing new forces like engineers, doctors, lawyers and academicians or those who are returning from abroad without old rigidities.

The economic growth that Singh has initiated in the country is impressive but it has not curbed parochial tendencies. His policies have increased the gap between the haves and the have-nots. In Nehru's days, the ratio between the top and the lowest was 10:1. Now it is thousand times more. The pertinent question which needs to be posed is: What after Singh, not after Singh who? His wasteful policies, although populist, have had an emaciating effect on 80 per cent of people. They are hardly bothered about the debate after Manmohan Singh who? They want bread.

Kuldip Nayar is a former Indian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and a former Rajya Sabha member.