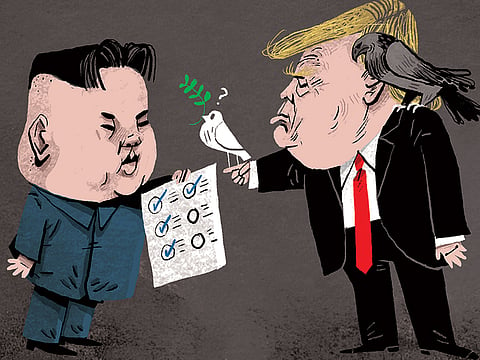

What will Trump give up for peace with North Korea?

Years of dealing with Pyongyang has shown that the regime never gives anything away for free

The announcement at the White House on Thursday evening that US President Donald Trump will meet the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un, within two months raises more questions than it answers. While the unpredictability of a meeting between these two unconventional leaders provides unique opportunities to end the decades-old conflict, its failure could also push the two countries to the brink of war.

The South Korean national security adviser, who had met with Kim in North Korea last Monday, made the announcement at the White House after meeting with Trump. He said that the North would consider denuclearisation, agree to cease weapons testing for now and accept the start of the annual United States-South Korea military exercises this spring.

After more than a year of heated rhetoric between the two leaders, and several North Korean missile tests, the United States and North Korea appeared headed for a collision course in the run-up to the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, last month. Vice-President Mike Pence’s cold shoulder to the visiting North Korean dignitaries at the Games presaged for many that the temporary respite of sports diplomacy would give way to a dangerous military crisis. The temperature on the Korean Peninsula seems to have been lowered for now.

While the South Korean government deserves credit for turning an impending crisis into an opportunity, there is no denying that Pyongyang’s apparent change of heart stems partially from the economic bite of Trump’s global sanctions, his so-called “maximum pressure” campaign. The North Koreans were probably also startled by reports earlier this year that the Trump administration was considering military options. But Kim also probably calculated that a pause in his country’s weapons testing now would not significantly erode Pyongyang’s ability to advance its nuclear programme.

The unanswered question going forward is what the United States is willing to put on the table for a negotiation. In years of dealing with North Korea, I have learned that the regime never gives anything away for free. To the extent that this administration has thought about diplomacy during its first year in office, it went no further than listing the things that the US would not do in future negotiations — for example, not give up sanctions, not pay for meetings, not make the mistakes of past negotiations.

Economic aid

Yet, what was distinct about the South Korean statement on Thursday was its description of conciliatory measures that Kim appears willing to take — a missile-test freeze, no response to American military exercises, and an invitation for a summit — but no detail on what Trump would be willing to offer in return. There appear to be two possible paths.

One would be to offer incremental energy and economic assistance and the lifting of sanctions for a freeze and eventual dismantlement of not just nuclear weapons, but also the long-range ballistic missile programme. The latter, in particular, has not been the topic of negotiations in almost two decades, and Trump could score a victory given his tweets during the campaign that the North’s ability to target the United States homeland was “never gonna happen” while he was president.

A second path might be bolder, and for this reason it might be more appealing to Trump. This would put much bigger carrots on the table, including diplomatic normalisation of relations and even the conclusion of a peace treaty ending the Korean War in return for denuclearisation. It would be ironic if Trump, an avowed hawk on North Korea, adopted this “big bang” approach to diplomacy advocated for years by doves.

But that is Trump’s world — black is white, front is back, chaos is good. Whether one of these paths or some hybrid is chosen, the administration would be well-advised to do four things. First, it must coordinate closely with its allies. US’ North Korea policy should never come at the expense of its allies. While South Korea is clearly on board, so must be Japan, whose leaders must be suffering a case of diplomatic whiplash after having been Trump’s biggest cheerleader in his campaign to pressure Pyongyang and consider military options.

Second, Trump should know that his negotiating leverage with Kim will only be effective if his sanctions pressure and deterrence capabilities remain strong.

In addition, any summit meeting cannot allow Pence’s pronouncements during the Olympics about North Korea’s human rights abuses to evaporate into thin air. Indeed, engaging the regime on improving its human rights record could be an important metric of the authenticity of the North’s diplomatic overtures. Finally, everyone should be aware that this dramatic act of diplomacy by these two unusual leaders, who love flair and drama, may also take us closer to war. Failed negotiations at the summit level leave all parties with no other recourse for diplomacy. In which case, as Trump has said, we really will have “run out of road” on North Korea.

— New York Times News Service

Victor Cha, a former National Security Council director for Asia, is a professor at Georgetown University and a senior adviser at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies.