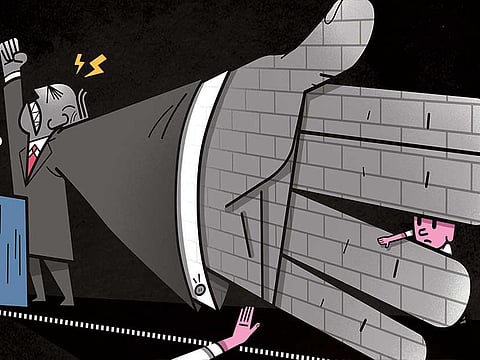

What explains the erection of so many borders?

From Fortress Europe to family separation, the once popular, turn-of-the-21st-century notion of a globalised and borderless world has come into question

Borders today are increasingly contentious, violent and tightly secured. And since 2015, the world has witnessed a rapid increase in the number of new border fences being constructed in a short span. Over the last three years alone, a staggering 63 new border fences have been constructed or are in the process of being constructed.

The once borderless Schengen Area now has border fences erected between member states and stringent border controls within the European Union. The divisive Brexit vote, based largely on the fear of immigrants, has altogether altered the very shape of Fortress Europe, giving rise to new questions about Britain’s borders and immigration policies as well as the very idea of Europe.

Across the Atlantic, the cacophonous chants to “build that wall” between the United States and Mexico have materialised into a Muslim ban, atrocious border-wall prototyping and, most recently, the brutal policy of separating immigrant children and families.

In South Asia, the pernicious Rohingya genocide has led to the creation of the largest refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Adding to this, border violence between India and Pakistan reached an all-time high in 2017 with the highest number of incidences of border violence. As these examples illustrate, the once popular, turn-of-the-21st-century notion of a globalised and borderless world has come into question. Instead, borders are being reinstated, redrawn and rebuilt — even in remote villages that have shared culture, languages and relations.

The recently completed border between Turkey and Syria, for example, boasts a so-called “electronic layer” that consists of close-up surveillance systems, thermal cameras, land surveillance radar, remote-controlled weapons systems, command-and-control centres, line-length imaging systems and seismic and acoustic sensors. There’s also an “advanced technology layer” of the project that includes wide area surveillance, laser destructive fibre-optic detection, surveillance radar for drone detection, jammers and sensor-triggered short distance lighting systems.

The notion of territorial loss is deeply ingrained in the breaking and forming of nations, identity and political states in South Asia.

Border technology, the development of newer forms of surveillance whether that includes drones and thermal imaging devices, or even the growing number of “volunteers” patrolling the borders between the US and Mexico, for instance, are indicative of this growing industry of division.

But if we are to critically examine what shapes the current border politics and thinking, it is vital to ask a few questions. What makes borders desirable? In a world that is arguably so digitally and economically connected, where goods, services and finance travel so freely, why is it so hard for humans to move?

To address these issues, one cannot ignore the impact of 9/11 and terrorism on global security practices. That said, the shift from traditional forms of violence to more dispersed forms of attacks like the events of November 2008 in Mumbai and, more recently, the Paris attacks in 2015, have displaced fears from the distant border to the nation’s heartland. It has infused security practices into our daily lives, with things like airport-like security at cinema halls, malls and hotels. X-ray baggage screening and body checks have become mundane rituals of urban life in India.

These changes have also influenced the way academics view the border as a concept. The traditional notion of the border, understood as a line in the sand located at the territorial limits of the nation-state, has been increasingly challenged. Scholars like Étienne Balibarand Nick Vaughan-Williams, for example, argue that borders have not only vacillated, but are also no longer where they used to be. Thinking of borders as verbs and not nouns, the emphasis from borders to bordering has brought to light new locations, practices and actors. Borders are also practised and enlivened at airports, train stations, detention centres, visa forms, border towns and complex algorithms that profile individuals.

They’re also practised with more frequency. Indeed, the pervasiveness of the notion of the border is both intriguing and perverse. In the US, for instance, individuals in towns and cities within 100 miles (161km) of the border can be subjected to random border checks and forced to produce their legal documents. This shifts the border from the precise border line to a far more encompassing border zone.

The recent Windrush scandal in the United Kingdom questions the legitimacy of its Caribbean immigrant descendants and their legitimacy in British society. This issue has successfully pulled the border from the periphery to the centre, but also raised questions about identity and citizenship in post-Brexit Britain. Furthermore, the everyday bordering of international students at British universities is also demonstrative of the new role of academics as border guards. In a sense, the question of where the border is located is also being transformed into who is performing these roles.

When it comes to India’s relationship with borders, it is first important to locate India’s thinking on the matter within its historical and political contexts. Historically speaking, the conflation of borders as a problem for post-colonial India can be linked with the partition and the ongoing territorial dispute over Kashmir.

While the inevitable association of borders in South Asia with the partition, wars and mortality cannot be done away with, it is equally necessary to move beyond these congenital associations, especially because the teleological link between the creation of the postcolonial nation states is seen in relation to bloody partitions — be it in 1947, when India was divided to create East and West Pakistan, or in 1971, when West Pakistan lost East Pakistan to the creation of Bangladesh.

The notion of territorial loss is deeply ingrained in the breaking and forming of nations, identity and political states in South Asia. In a way, the historical burden of this has also led to an overly nationalist understanding of the nation whereby territory — with an emphasis on things like blood and soil — is made sacred. More notably, the notion of Bharat Mata (Mother India), or the anthropomorphic distortion of India as Mother India, renders the borders of the state as highly emotional and evocative issues.

Border scholar Jason Cons defines India’s borders as “sensitive spaces” and explains sensitivity in terms of both political sensitivity as well as places that are associated with unexplainable fear and anxiety. This sensitivity state — or what Sankaran Krishna defines as cartographic anxiety typical of a postcolonial nation — runs deep in psyches of the state, polity and people. Considering the hypersensitivity to maps and the depiction of India’s borders in foreign publications like the Economist or the fact that India’s borders with Pakistan are not only electrically charged and floodlit, but are also visible even from space, elucidates the extent of border fixation and anxiety.

In many ways, the physical unfixity of the Line of Control between India and Pakistan is what has rendered this border line fixed in the minds of politicians and citizens alike, whereby the borders of Bollywood and cricket remain firmly outlined for Pakistanis.

Borders of post-colonial India, too, are not limited to their territorial location or material articulation, but are today subtly articulated through the increasingly exclusionary narratives of the nation sifting through those who belong and those who do not. The unofficial housing apartheid that occurs in urban spaces against minority religious communities, or the bogey of “Love Jihad” and attacks on “anti-nationals” consistently outline stereotypes, prejudice and everyday forms of bordering.

Although they lack the infrastructure of fences and guards, they still perpetuate invisible fences of difference and division.

— Worldcrunch, in partnership with The Wire/New York Times News Service

Prithvi Hirani is a columnist with a specialisation in international relations. borders and identity politics.