West’s Russia policy is inconsistent

Both Trump and May have gone out of their way to placate Putin, despite Moscow’s seemingly subversive strategy

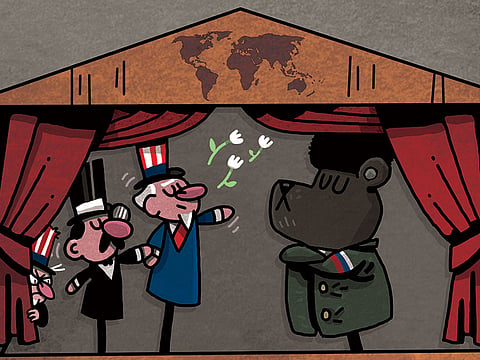

There are not many laughs to be had from international diplomacy, but US foreign policy in the age of President Donald Trump provides a grim kind of comedy all the same. Recently, the world’s diplomats allowed themselves a chuckle at the risibly inconsistent US approach to Russia, in which the State Department whacks Moscow with sanctions even as the US president murmurs sweet nothings into the ear of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

When it comes to Russia, the US has become the Jekyll and Hyde superpower. Just three weeks ago, Trump stood next to Putin in Helsinki, unable to utter so much as a word of criticism of the Russian dictator who, a vast body of evidence shows, acted to subvert the American democratic process in 2016. And yet a few days ago the US announced new sanctions on Moscow as punishment for the attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury with a lethal nerve agent.

What a joke, foreign ministry types will be saying to themselves. The Trump administration is divided against itself, a White House spokesperson only formally endorsing the State Department move a full two days after it had happened. It emerged that the president’s own national security adviser, John Bolton, plotted with European diplomats to rush through a new Nato strategy document when Trump wasn’t looking — in order to deny him the chance to wreck it and, especially, to soften its tough stance on Russia.

Britain has, of course, been tough on the use of a Russian-made nerve agent on the streets of a British city. Indeed, one of British Prime Minister Theresa May’s rare diplomatic successes was in persuading a host of allies to follow the UK lead in expelling Russian embassy personnel following the Skripal attack. In this, May is in step with the US State Department.

When it comes, however, to evidence of Russian intervention in Britain’s democratic process, specifically the European referendum of 2016, May is more like Trump: remarkably, unaccountably relaxed.

This week details of the lucrative goldmining deal emerged. Dangled by the Russian ambassador in front of Arron Banks, the main donor behind Leave.EU (in the lead-up to the Brexit vote), it involved tempting PowerPoint presentation Moscow made to Banks — opening with a slide of shimmering gold bars, complete with Cyrillic engraving, alongside a Russian flag.

Role in Brexit

At the very least, you would think the UK government might be curious as to why Putin’s top diplomat in London would favour Banks not only with multiple meetings — four at last count, though Banks used to say they had met only once — but with such exclusive “opportunities not available to others”, to quote the pitch document. Banks says he didn’t take up the golden offer, which included a promise of support from a Kremlin bank, much as Trump says the Trump Tower meeting between his son and Russian representatives promising dirt on Hillary Clinton “went nowhere”. But that is hardly the point. That Russia was ready to do its bit to make Brexit happen is already well-established. We have had for nearly a year the documented proof that the Kremlin ran a social media campaign through the Internet Research Agency, its troll farm in St Petersburg, using more than 400 fake Twitter accounts to push for a British exit from the EU.

Where, though, is the outrage from the British government? Even US Republicans acknowledge that Russian activity in 2016 constituted an attack on American democracy, on the right of American voters to make their own decisions free of foreign intervention. Where is the equivalent condemnation, or at least demand for answers, from May and her ministers? In a way, the UK situation is worse. The US is at least conducting an inquiry into Moscow’s campaign to sway the ballot two years ago, thanks to the investigation led by former FBI director Robert Mueller. True, that effort is opposed by Trump himself — who calls it “an illegally brought Rigged Witch Hunt” and who may eventually move to shut it down — but it has already borne fruit, including charges against a dozen Russian intelligence officers accused of interfering in the 2016 election. We still have no such probe in Britain, not by the police or the National Crime Agency, let alone a judge. Nothing.

For Trump, the motive for opposing Mueller is obvious: he fears that to admit Russian subversion would be to cast doubt on his own electoral legitimacy. For May, the calculation is not dissimilar: hers is now a Brexit government, and she dares do nothing that might undermine the so-called “will of the people”.

But the result is the same. The UK government, like Trump’s, faces two contradictory ways on Russia — tough on one attack by Moscow, bizarrely forgiving of another.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Jonathan Freedland is a noted columnist and writer.