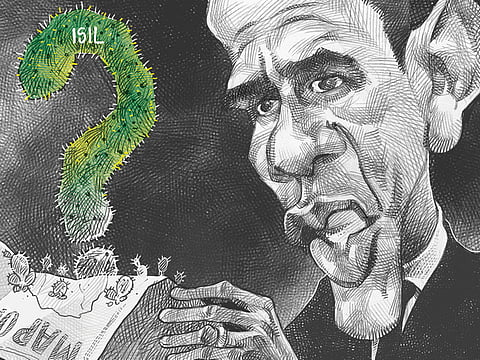

US needs to offer clarity in what it is doing in Iraq

A clear American position would help create a political framework through which Arabs can rally to defeat Isil

No Arab country backs the wild extremists of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isil), even if several local groups have formed tactical alliances with them. However, there is not yet any concerted action to stop their advance and remove them from the political spectrum.

The Iraqi government is desperately trying to rally its own forces and to work with the Kurdish peshmerga, but it has not yet found regional allies who are willing to send forces or logistical support to defeat this dangerous fringe group that has grabbed power in parts of Iraq and Syria.

This alarming lack of purpose is reflected in how the world’s superpower is confused about what it is trying to do. President Barack Obama has offered some deeply contradictory messages as he first authorised humanitarian support on a strictly limited basis, but then talked of refusing to allow Isil to continue and the necessity of a long drawn-out struggle.

It is clear that the growing acceptance of the importance of defeating Isil is creating some very uneasy alliances, as the Iranians and Bashar Al Assad regime in Syria offer to work with the Americans and Saudis. This fits into the new pragmatic search for stability that will dominate the Arab world for the next few years, as regional and world powers work with any non-Islamist who can regain control of a nation state and impose an end to civil war and chaos.

But this needs leadership. The Arab world is still hesitant to rush to back the new Iraqi government given the miserable record of outgoing premier Nouri Al Maliki, and is shocked that Al Assad will use the new search for regional stability at all costs to get off scot free and rehabilitate himself.

US drifts to war

The Americans have not helped the regional search for leadership by their own policy muddle as the White House seems to hide its intention to get into another Arab war.

What started as a humanitarian mission turned into a willingness to take sides in the Iraqi civil war, which then became a willingness to get involved in military action in Syria.

All these different military objectives come from very senior US officials, including the president, the secretary of defence, and the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, all of whom should have the same military objectives.

Obama announced on August 7 that he had authorised a limited number of US military airstrikes “if necessary” against Islamist militants in Iraq as they advanced toward American personnel in Kurdistan. But very soon after this “limited” action, the US sent several hundred military advisers into Iraq, and started improved military supplies to the Iraqis and the Kurds. The mission creep had started and became clearer when Obama said that the US could not accept the Isil caliphate.

On August 7, Obama made great play of being asked by the Iraqi government to conduct humanitarian missions to help religious minorities stranded in the violence. Declaring that “America is coming to help”, he said that the US was giving aid to the 50,000 Yazidis facing genocide as they were stranded on Mount Sinjar. They had been forced to flee their homes as the Isil militants advanced.

Obama was clearly embarrassed by the charge that he was sending US forces back into a war in Iraq that he promised to end. That is why he insisted that there is no American military solution to Iraq’s problems and the country must seek a political solution.

This line was repeated endlessly by White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest and other administration officials, but two weeks later, Obama said that the challenge posed by Isil would “take time” to combat: “There are going to be many challenges ahead,” he said.

Obama’s readiness to contemplate long-term combat and a general assault on Isil was being echoed by many of his senior officials. General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which makes him the senior-most American in uniform, asserted that Isil will not be defeated without being attacked in Iraq and also Syria. Dempsey added that Isil cannot be “defeated without addressing that part of the organisation that resides in Syria”.

Gravest threat

Secretary of Defence Chuck Hagel has said that the Isil is the gravest threat from Islamist militancy the US has ever encountered.

A thoroughly alarmed Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said this week that she backed the limited mission Obama had described to provide “humanitarian assistance; protect Americans; recognise that Isil is a threat; no boots on the ground”.

The growing drift into war led the House of Representatives to vote in mid-August overwhelmingly in favour of a resolution which barred Obama from deploying American forces in a “sustained combat role” in Iraq without specific authorisation.

Quite what “sustained” and “combat” mean is hard to tell in the confused atmosphere in Washington.

If the US has gone to war to defeat Isil and support the Iraqi government, it should say so. If the president is dodging an angry and suspicious Congress, he is also failing to give clarity to his Arab allies who may want to support the effort to stop Isil, but need a clear political framework through which they can offer their support.

See also A2 Page 2