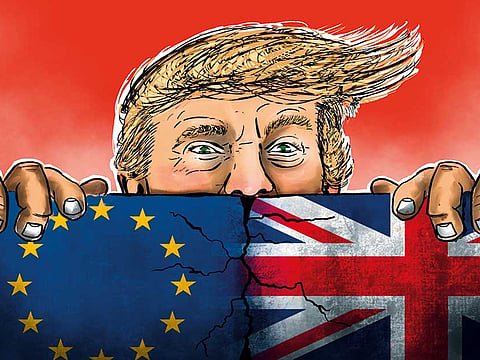

Trump’s Brexit criticism is out of place

US president’s broadside at May and praise for Johnson are unwelcome interventions in British politics

Although many American presidents have paid visits to England, there has never been a visit quite like Donald Trump’s this week. But then, has there ever been a US president quite like him?

Almost as soon as Trump was inaugurated, the British prime minister, Theresa May, rushed to Washington to meet him, with what many of her compatriots thought unseemly haste. It wasn’t made better when they embarrassingly held hands and were photographed in the Oval Office with the bust of Sir Winston Churchill between them.

They exchanged the usual platitudes about the special relationship. The prime minister extended an invitation to Trump to pay a state visit to London.

The curious nature of the ongoing visit could be highlighted by the official absence of the one British politician Trump seems eager to see, and who may return the eagerness, although it’s not clear what they have to give one another, apart from bromantic mutual admiration. “Boris Johnson”, said Woody Johnson, the American ambassador in London, “has been a friend of the president”, with whom he has “a warm and close relationship”. Until this week, Johnson was foreign secretary. He attended May’s crisis Cabinet meeting at Chequers and offered her his full support. Three days later, he resigned, taking care to make it a photo op, with the picture of him writing his resignation letter released to the media. If he’s trying to supplant May, this combination of cynicism, inconsistency and disloyalty could not have helped his chances. Nor will meeting Trump obviously endear Johnson to the British public, although Johnson might see it as a way of further destabilising May. And, come to think of it, Trump might like that, too, given the way he has gloated over the British government’s “turmoil”.

Despite the superficial gulf between Trump and the silver-tongued Johnson, between the author of The Art of the Deal and the author of The Churchill Factor, there may be a real affinity. And that affinity could paradoxically help explain just why the “special relationship” is such a fantasy. Two years ago, Johnson threw his weight behind the “Leave” campaign in the Brexit referendum, to decisive effect, many people think. Characteristically, he wrote two columns at that time. One argued for “Remain” and one for “Leave”. At the last moment, he tossed a mental coin — or rather, one may suppose, he decided which would better advance his ambition.

Egregious conduct

At that time, Johnson had an adoring personal following. The Brexit referendum was just over two years ago, in June 2016. Then came the upset of November, the election of Donald Trump as United States President. Since then, quite apart from his egregious conduct over immigrants, his glad-handing with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un and Russian President Vladimir Putin, and his derision of Nato, Trump has never missed an opportunity to say what a good thing Brexit is, which is none of his business. His enthusiasm for Brexit isn’t because Trump feels any deep love for British tradition, but because he hates the European Union as a competitor. And he can scarcely be bothered by what looks like Russian interference in the referendum.

The worst thing of all about so many of the leading Brexiteers like Johnson was that they campaigned for Leave out of cynical calculation of advantage within the Tory party, but they never expected to win, and they had no idea what to do if they did. That has become clearer with every day that has passed since the referendum, and the more Brexit turns into a monumental train wreck, the more hysterical the Brexiteers become.

Three years ago, Johnson said that Trump was “clearly out of his mind”. Recently he has taken to singing the US president’s praises, and comparing him favourably with May. By doing so, he does inadvertently perform a service — and so does Trump when he boorishly intervenes in British politics. As Sir Max Hastings, the journalist and military historian, noted, Churchill invented the concept of the special relationship for reasons of political expediency, and was then the first of many prime ministers to find that it didn’t exist. Above all, it rested on a denial of reality: The reality that the US, like all great powers in history, will in the end follow its own interests and objectives. (Consider the Iraq War, when the relationship was embodied by the then US president, George W. Bush, and the then British prime minister, Tony Blair.)

Long ago, Churchill had told the French general Charles de Gaulle that if he had to choose, he would always choose the open sea, and America, against Europe. After the war, ambiguity persisted in British policy, until we turned towards the continent 45 years ago, when the United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community. Now we’ve turned our backs on Europe again — and in the age of President Trump. What a time to do it!

— Washington Post

Geoffrey Wheatcroft is an award-winning British journalist, columnist and author. His books include best-sellers like The Strange Death of Tory England.