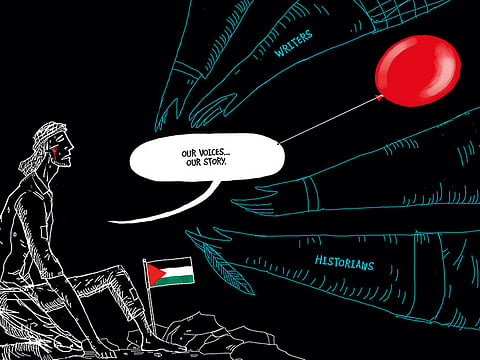

Time to reclaim the Palestinian narrative

Writers must continue to internalise and communicate Palestinian voices so that the world can appreciate the story as told by wounded but tenacious victors

The story of Palestine is the story of the Palestinian people, for they are the victims of oppression and the main channel of resistance, from the time of the creation of Israel on the ruins of Palestinian villages in 1948. Had Palestinians not resisted, their story would have concluded then and their history relegated to nothing more than that. Those who admonish Palestinian resistance, armed or otherwise, have little understanding of the psychological ramifications thereof, such as a sense of collective empowerment and hope among the people. In his introduction to Frantz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth, Jean-Paul Sartre describes resistance as a process through which “a man is recreating himself”.

For 70 years, Palestinians have embarked on this journey of the recreation of the “self”. Their resistance, in all forms, moulded a sense of collective unity, despite the numerous divides that have been erected among them. Relentless resistance, a notion now embodied in the very fabric of Palestinian society, denied the oppressor the opportunity of emasculating Palestinians or reducing them to helpless victims and hapless refugees. The collective memory of the Palestinian people must focus on what it means to be Palestinian, defining the Palestinian people, what they stand for as a nation, and why they have resisted for so many years. A new articulation of the Palestinian narrative is necessary now more than ever. The elitist interpretation of Palestine has failed and is as worthless as the Oslo Accords. It is no more than a tired exercise in empty cliches aimed at sustaining American political dominance in Palestine as well as in the rest of the Middle East.

The peace process is dead, but the Palestinian people are still resisting; unsurprisingly, the people are mightier than a group of power-hungry individuals. Grassroots resistance is not constrained by the frivolous politicking of Palestinian National Authority President Mahmoud Abbas and his like.

Abbas and his men have not only muzzled the political will of the Palestinian people and falsely claimed to represent all Palestinians, but have also robbed Palestinians of their narrative, one that actually unites the fellahin (peasants) and the refugees, the occupied and the shattat (diaspora), into one distinct nation.

It is only when the Palestinian intellectual is able to repossess that collective narrative that the confines placed on the Palestinian voice can finally be broken. Only then can Palestinians truly confront the Israeli Hasbara and US-Western corporate media propaganda and, at long last, speak unhindered.

Perhaps most importantly, if the story of the people is to be told accurately and fairly, the storyteller must be a Palestinian. This is not a veiled ethnocentric sentiment, but rather confirmation that facts change in the process of interpretation, as explained by the late Palestinian professor Edward Said, “Facts get their importance from what is made of them in interpretation … Interpretations depend very much on who the interpreter is, who he or she is addressing, what his or her purpose is and at what historical moment the interpretation takes place”.

Dr Soha Abdul Kader describes Middle East history studies as generally “bearing the imprint of orientalism”, with limited sources and methodologies used to study the region. The same is true of Palestinian studies. Most notable since the peace process commenced, Palestinian historiography largely neglected ordinary people and remained hostage to narrating the history of the elites, their political institutions, diplomatic events, and their self-indulgent understanding of conflict, whether socio-economically or in terms of conflict. Among the average Palestinian citizen, however, “history from below” is what captures attention. Adab Al Sijun (prison literature) has remained a staple in most Palestinian bookstores and libraries to this day. “History from below”, in contrast to “the Great Man Theory”, contends that while individuals or microcosmic social groups (ruling elites and their benefactors) might prompt certain landmark events, it is largely popular movements that significantly influence long-term outcomes.

The First Palestinian Intifada demonstrated this assertion. Thus, the constant calls for a “Third Intifada” by many Palestinians are not brought upon by a whim; rather, they come from the historical success of such movements from below. The current popular mobilisation at the Gaza border is the latest manifestation of such truth.

There are obstacles to these calls for another popular movement led from below, from the challenges of raising awareness and effective planning, as well as the ruthless attempt by Zionist (as well as many western) historians and institutions to replace the Palestinian historical narrative with their own.

In the Zionist Israeli narrative, Palestinians, if relevant at all, are depicted as drifting nomads, an inconvenience that hinders the path of progress — a duplicate narrative to the one that defined the relationship between every western colonial power and the resisting natives — perpetually.

It is incumbent upon us — not only Palestinians but also those who wish to present a truthful understanding of our historic struggle — to reclaim the Palestinian narrative and dislocate the propaganda-driven Zionist one.

From the latter’s perspective, Palestinian existence is an inconvenience that was meant to be only temporary. “We must expel Arabs and take their places,” wrote Israel’s founding father, David Ben Gurion.

This type of brazen discourse has consistently translated to the kind of military aggression that ethnically cleansed nearly a million Palestinians from their land in 1947-48 and continues to drive the colonists’ enterprise in the Occupied Territories.

Between the rock of Israeli occupation and Hasbara, and the hard place of Palestinian leadership acquiescence and failure, Palestine, Palestinians and their story have been trapped and misconstrued.

It is time for us to step up. We, as Palestinian writers, historians and journalists, must continue to assume the responsibility of reinterpreting Palestinian history and internalising and communicating Palestinian voices, so that the rest of the world can, for once, appreciate the story as told by wounded but tenacious victors.

Ramzy Baroud has a Ph.D from University of Exeter, UK. He is also a Non-Resident Scholar at Orfalea Centre for International Studies, UCSB.