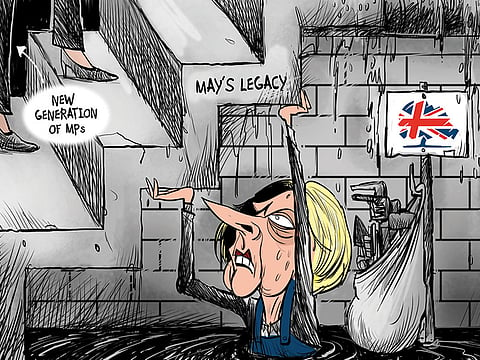

Theresa May can still save the Conservatives

While it is too late for the British Prime Minister to save herself, she can lay a good succession plan for a strong union

We have been here before, and so has British Prime Minister Theresa May. I recall visiting her at the 2003 Conservative conference in her makeshift office at the Blackpool Winter Gardens. As Tory chair, she was obliged to insist that Iain Duncan Smith, the embattled party leader, was safe from the mischievous plotters, and would march on regardless. But her wanfeatures told a different story.

Duncan Smith did indeed receive 17 standing ovations during his combative conference speech. But, 20 days later, his MPs sacked him in a vote of no confidence. His authority had simply been worn down by a series of resignations, plots and embarrassments. For months, the whips had kept his opponents at bay. But in the end even they turned — decisively so.

Usually there is a stop-go pattern topolitical rebellion: the plotters assert themselves, the loyalists circle the wagons, and order is notionally restored. Except that it isn’t, not really. Once the principal topic of conversation in a party becomes the fateof the leader, it is almost an axiom that he or she is doomed.

So the prime minister would be ill advised to draw much comfort from the decision of most senior Tories to rally round her this weekend and — at least publicly — to distance themselves from Grant Shapps, outed last week as a ringleader of the plot to depose her. Their support is entirely provisional, and in many cases spectacularly hypocritical.

Indeed, the rubbishing of Shapps in the past few days has been pathetic. Though his chairmanship of the party between 2012 and 2015 was not without controversy, he is an able politician who knows the Tory movement inside out. The leaden-footed campaign to present him as a marginal figure is ridiculous. Like Ed Vaizey — the MP for Wantage, who has also raised doubts about May’s leadership — Shapps is treating the voters like adults by saying explicitly what everyone knows his colleagues are muttering in private.

Yet whatever his fate, the fundamentals of May’s position will not change: the wound dealt by the Tories’ election performance is now deeply infected.

Two arguments are routinely advanced for the status quo. First, it is suggested that May must stay in place until the Brexit talks are concluded. The idiot logic of this claim is that the most important negotiations to face this country since the second world war require the smack of weak leadership.

Second, and just as ludicrously, it is said that May has no plausible successors. Whether or not you like or agree with any of them, it is idle to deny that Amber Rudd, David Davis and Philip Hammond, to name but three, have perfectly reasonable claims as potential candidates. Johnson has become a fabulously divisive figure, but won two mayoral elections in a Labour city. Which brings me to Ruth Davidson. If there is to be a leadership contest (and there will be, sooner than you think), it would be ridiculous if this talented politician were not a contender. It was fascinating to watch Tory activists behold the party’s Scottish chieftain last week. What to make of this pugnacious, charismatic, hugely articulate, socially liberal, pro-remain honorary army colonel?

Electoral reach

As she delivered her barnstorming speech, one could see that the audience was both baffled and bewitched. Even the party’s traditionalists know she is something special, with a potential electoral reach far beyond the core Tory vote. They sense she is national leadership material, and that she scares Labour. They would like a closer look. But how? She is, after all, a member of the Scottish parliament, with no official locus in the Westminster village. To adapt the metaphor made famous by Shimon Peres: “The good news is, there’s light at the end of the tunnel. The bad news is, there’s no tunnel.” To which the answer should be: build one. And here’s how. The PM has always been well disposed towards Davidson, and relaxed in her company. Early in her premiership, I remember May’s aides telling me that there were times when they “put Ruth in front of Theresa” to cheer her up or make a point. So who better to replace Patrick McLoughlin as party chair?

All prime ministers pay lip service to the importance of devolution and the devolved assemblies. But May would give real substance to this claim by appointing Davidson to a national role. Nowhere, by the way, does it say that a Conservative chair needs to be an MP. Of the 42 individuals who have so far held this post, 11 have been in the House of Lords. Why not a member of the Scottish parliament?

The “dual mandate” rule means furthermore that Davidson, once established as a Westminster figure, could also seek election to the Commons once a vacancy arose. Johnson, after all, was simultaneously mayor of London and an MP. Between 1998 and 2004, the late Ian Paisley was an MP, MEP and a member of the Northern Ireland legislative assembly.

None of this need take long. It would provide Davidson with a strategy that did not force her to desert the Scottish party abruptly, and would enable her to stake her claim on the national stage as a champion of the union and a sane Brexit. Those who say she should wait are doing her and the Tory party no favours. In modern politics, once your name is in the frame, reticence is fatal. Now is her moment — but it will not last indefinitely.

As for May, this course of action would offer her the chance of a dignified exit and — even better — of a proper legacy. This is not the time for half-measures. If the PM wants a successor serious about tackling “burning injustice”, she knows what she has to do.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Matthew d’Ancona is a noted British journalist, editor and columnist.