The immigrant story at the heart of America

I tell my American story, knowing that it is the story that can be told by millions of others

Immigration is a personal matter for me, as it is for many Americans. Unless you are a Native American descendant of the indigenous peoples who were displaced by the settlers who first came to the country, or an African-American descendant of those who were brought here in bondage as slaves, all Americans are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants.

Because of the central role immigration has played in shaping the American experience, many families are defined by why and how their ancestors came and started their lives in this New World, the hardships they endured, and the successes they realised. We tell their stories to one another and to our children because they remind us who we are.

I had the privilege of working with former United States vice-president Al Gore, when he appointed me, in 1993, to serve as co-chair for a project he was launching to support Israeli-Palestinian peace. On my way over to the White House to meet him for the first time, I could not help but be moved as I thought of the sweep of history that had brought me to this point. And so, as we sat in his West Wing office and he asked me to tell him a bit about myself, I responded: “My father came from a one room, mud floor, stone house in the hills of Lebanon. He entered America illegally and became a citizen only 50 years ago. Today, his son is sitting with the vice-president of the US. It might be a bit abbreviated, sir, but that’s my story.”

My dad and his four brothers, two sisters, and mother, like millions of others in the pre and post-First World War period, came to America to escape economic hardship and political strife and to find opportunity and freedom. The life they left had been difficult. The life they found in America also had its share of problems.

Like so many other Syrian-Lebanese, they were peddlers — and were reviled for it. Called “parasites” and “Syrian trash”, they suffered harsh discrimination. Efforts were made to have them excluded. For the flimsiest of reasons, many were rejected upon entry or sent back. My mother’s father arrived at Ellis Island with his brother. My maternal grandfather was admitted, his brother was not. My grandfather was told that the reason for his brother’s exclusion was glaucoma. They never saw each other again, although my grandfather did learn that his brother ultimately settled in Brazil. I grew up wondering about my cousins, who and where they were.

My father was the last of his family to arrive. By the time he was ready to make the voyage, visas had been suspended for Syrians. The only way he was able to join his family was to enter the US illegally. He later benefited from amnesty and became naturalised in 1942.

On both my mother’s and father’s sides, despite the hardships they experienced, the bet they had placed on risking everything to come to America paid off. They built businesses, started families, bought homes, educated their children and watched them prosper.

I tell my American story knowing that it is the story that can be told by millions of others. I also know this: When I get into a taxi and meet the immigrant driver from Nigeria, or go to a restaurant and am waited on by a recent immigrant from Tunisia, or try to speak (with the few words of Spanish I know) to the Salvadorean woman who comes to clean our office, or park my car and pay the fee to recently arrived Ethiopian attendant, or think of the Bosnian refugee family that bought and refurbished my family’s old home in Upstate New York — I know that less than a generation from now, their children will be able to tell the same story about the heroic sacrifices their parents made to give them the chance to prosper in freedom in America.

This is who we are. It is the collective story of our past and it is the story that still defines who we are and want to be in the future. We came from many shores, often escaping strife and hardship, all seeking the opportunity to prosper in freedom.

For all of us, immigrants and the descendants of immigrants, the words inscribed on the Lady in the Harbor [Statue of Liberty] define our sense of what America means:

‘Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teaming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me.

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!’

No other words better describe the promise that America had held and still holds out to the world.

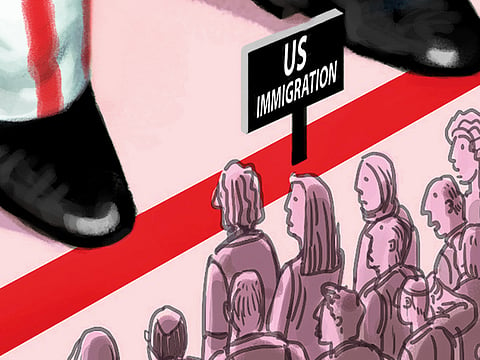

And so when President Donald Trump unveiled a new immigration bill last week, that would cut in half the number of refugees as well as the overall number of immigrants to be allowed in, end the lottery system that provided visas for individuals from countries that have been historically under-represented, and favour visa applicants with special skills who speak English, I was shaken to my core.

And when, later that same day, a presidential aide gave a mean-spirited defence of this “reform” proposal, in which he rudely dismissed as irrelevant the words on the Statue of Liberty, I was outraged.

This is not the first time in American history, that those espousing a nativist, exclusionary worldview have attempted to limit immigration and, in the process, redefine the very meaning of America. We have faced this challenge before. Each time, however, we have fought this “let’s-close-the-door-behind-us” mentality, we have won. Now, this fight has come to my generation and fight back we must — to honour the legacy left to us by our ancestors and to keep alive the promise of America for future generations.

Dr James J. Zogby is the founder and president of the Arab-American Institute, a Washington, DC-based organisation that serves as a political and policy research arm of the Arab-American community.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox