The forgotten Palestinians: As elephants fight, the grass suffers

Factionalism and discontent have resulted in two narratives with opposing contexts

In and around the southern mountains of Hebron (Al Khalil) there are thousands of people who dwell in tents, huts and caves. Before Israel came to existence in 1948, they moved about unhindered in the vast area, tending to their crops, sheep and traditional way of life as they had done for generations.

Expectedly, things have changed for the Hebron mountain dwellers who continue to fight incessant waves of ethnic cleansing. First it was to make room for the Israeli city Arad, and starting in the early 1980’s, for Jewish colonies. Since then, their existence has been registered as a side note for Israeli colony planners, who are neither concerned by a few thousand Palestinians in Hebron, or millions across the Occupied Territories.

As I followed the news of yet another Hamas-Fatah meeting in Egypt on January 9, which included more lofty promises about unity, common strategy and all the rest, I could not trace the exact logic of why the mountain dwellers were the first group of Palestinians to come to mind. Not that Hebron is too far from Ramallah or Gaza, or even Cairo, but it is mostly because the suffering of ordinary Palestinians is increasingly removed from the factional concerns of the two leading Palestinian groups.

What contributes to this oddity is that despite the fact that Palestinians in the Occupied Territories number four million people, they have two governments, two leaderships and numerous ministers, all the while controlling actually nothing on the ground. They don’t even control their exit or entry into occupied East Jerusalem, the West Bank or Gaza.

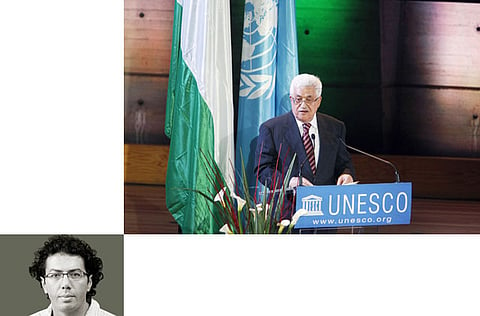

The triumphant visit of Hamas chief Khaled Mesha’al to Gaza early December would have not actualised without an Israeli nod or at least a promise that it will not attempt to assassinate him. The same goes for the Palestinian Authority (PA) and Fatah leader Mahmoud Abbas, whose personal movement in and out of the West Bank can only take place through detailed coordination between the PA and Israeli security forces.

Yet, Palestinians were assured once more that the last set of meetings in Cairo, under the government of Egyptian President Mohammad Mursi were particularly more promising and took place in a refreshingly more pleasant environment. The news of the pleasantness of the meeting was splattered across headlines in Palestinian and Arab media. The redundancy of it all is itself most tiring. But a bigger issue is how will this affect the plight of the cave dwellers? The besieged people of Gaza? The unpaid and occupied West Bankers? The prisoners on hunger strikes? And the numerous groups, big or small that continue to suffer throughout Palestine?

A member of Hamas’ political bureau, who participated in the Cairo talks, told AFP that “the two parties agreed to call on all Palestinian factions to implement the reconciliation agreement.” Izzat Al Rishq was of course, referencing the April 2011 unity agreement between Mesha’al and Abbas, which determined that legislative elections would have been held before the end of May 2012. Of course, no elections took place and both parties continue their self-defeating muscle flexing. This is of course a great service to Israel and a greater disservice to the common cause of the Palestinian people.

Historically there has been a leadership deficit in Palestine and it is not because Palestinians are incapable of producing upright men and women capable of guiding the decades-long resistance towards astounding victory against military occupation and apartheid. It is because for a Palestinian leadership to be acknowledged as such by regional and international players, it has to excel in the art of ‘compromise’. These carefully molded leaders often cater to the interests of their Arab and western benefactors, at the expense of their own people. Not one single popular faction has resolutely escaped this seeming generalisation.

Such reality has permeated Palestinian politics for decades. However, in the last two decades, the distance between Palestinian leadership and the people has grown by a once unimaginable distance, where the Palestinian has become a jailor and a peddling politician or a security coordinator working hand in hand with Israel.

The perks of the Oslo culture have sprouted over the years creating the Palestinian elite, whose interest and that of the very Israeli occupation overlap beyond recognition of where the first starts and the other ends.

While Hamas remained largely immune from the Oslo circle — as Abbas and his men enjoyed its numerous political and economic perks — it too is becoming enthralled by the prospects of regional acceptance and international validation. Its strictly factional agenda and closeness to some corrupt Arab countries raises more than question marks and there is the prospect of heading in the same direction as Fatah leaders did over two decades ago.

And while the ‘unity’ charade continues, the inflammatory rhetoric and rival claims continue as well. The chasm is growing despite the supposedly sober facts that Hamas allowed Fatah to celebrate the anniversary of its birth in Gaza, while the latter did the same in the West Bank. Supporters of both parties brazenly used their parades — which took place under the watchful eyes of Israeli drones — to exhibit their strengths, not in relation to the Israeli military occupation, but to their own pitiful factional propaganda.

Oddly enough, if the calculations of Palestinian factions are accurate regarding the attendees of their rallies, the population of Gaza may have suddenly morphed to exceed four million, a remarkable jump from the 1.6 million of few weeks ago. This is the actual number of the Gaza population per United Nations statistics.

This miserable legacy of Palestinian factionalism is taking place against the backdrop of a slowly brewing movement in Israeli jails. Palestinian political prisoners continue to place their faith in their own ability to endure hunger, gaining international solidarity with their cause. Samer Issawi, a Palestinian prisoner who as of January 10 completed a 168-days of a hunger strike in protest of his unlawful detention by Israel, is hardly a unique phenomenon. He is an expression of the very much present, but snubbed Palestinian collective, whose fate doesn’t fall into the political agenda of any faction.

Issawi is one of seven brothers, six of whom spent time in Israeli prisons for their political beliefs. One of the brothers, Fadi, was killed by Israeli soldiers in 1994, a few days after celebrating his 16th birthday. Even their sister Shireen was arrested by Israeli soldiers during a hearing concerning her brother Samer on December 18. On that day, “Samer was publicly beaten in the Jerusalem Magistrates Court after he tried to greet his family,” reported the Palestine Monitor. “He was dragged from his wheelchair and carried away, repeatedly crying out as he was hit on his chest by the guards around him.”

It is almost impossible to combine the two narratives. Factionalism and hunger strikes can only be understood in opposing contexts; five-star hotel conferences that yield nothing and cave dwellers braving bulldozers are barely two related news items.

Not only do Palestinians have no country and two governments, but they also have two rival narratives. One is of competing factions manipulated by regional and international powers while the other is of a penniless group of brave men and women who fight for their very survival, basic rights and freedom.

This is the dichotomy with which Palestinians must now wrangle. The path they will finally seek shall define this generation and demarcate the nature of the Palestinian struggle for generations to follow.

Ramzy Baroud is an internationally-syndicated columnist and the editor of PalestineChronicle.com. His latest book is: My Father was A Freedom Fighter: Gaza’s Untold Story (Pluto Press).