Struggle for power in Egypt

There is a chance the military might hand over all powers to the president

All politics is a struggle for power. In authoritarian regimes, the power holders use brutality to suppress dissent and use propaganda to fabricate legitimacy through rigged elections. In democracies, the struggle for power is channelled through the competitive nature of the electoral process and mediated by the tacit acceptance of the supremacy of the rule of law.

The massive protest that erupted in January 2011 quickly developed into a popular revolution that, with every achievement, pushed Egypt further into a period of convoluted transition to democracy. This has been characterised by the continued struggle for power between the revolutionaries and the guardians of status quo.

The Egyptian revolutionaries demanded the end of the authoritarian rule of former president Hosni Mubarak. In acceding to the revolutionaries’ demand and stepping down, he said he had asked the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (Scaf) to run the affairs of the country.

This brought the two best organised institutions in the country — the army and the Muslim Brotherhood — face-to-face in an uncomfortable confrontation.

The army was a popular institution. It produced the Free Officers Movement, which led a bloodless coup and overthrew a corrupt monarchy in 1952. When Jamal Abdul Nasser emerged as the new leader in Egypt, he made people feel that the coup was a genuine revolution on behalf of the people. His policies at home promoted social justice. Regionally, he championed Arab nationalism and non-alignment, which enhanced the prestige of Egypt and the popularity of Nasser.

But fundamental freedoms suffered, as did the Muslim Brothers under Nasser. President Anwar Sadat, also from the Free Officers, enjoyed a measure of popularity for having masterminded an honourable military performance in the 1973 war. That set the stage for the return to Egypt of Sinai, which the Israelis had occupied since 1967. Fundamental freedoms suffered even more under Sadat who engaged in periodic purges. Hosni Mubarak — also from the army — who became president after Sadat’s assassination, modified the mission of the army and focused on internal security, as he implemented neo-liberal economics, reduced or eliminated social subsidies and accommodated Israeli hegemony in the region.

The Muslim Brotherhood, although officially banned, continued to provide social and medical services and to preach that Islam was the solution. When calamities occurred in Egypt, such as when a building collapsed, the Muslim Brotherhood was usually the first to arrive on the scene.

The Muslim Brotherhood opposed the so-called normalisation of relations with Israel and remained steadfast in its support for the Palestinian cause.

In the 2005 legislative elections, it is widely believed that had it not been for massive rigging by the Mubarak regime, the Brotherhood would have won a majority.

Thus, the January 25 revolution in Egypt gave the Muslim Brotherhood the stature of legitimate opposition and the credibility of being part of a revolution demanding democratic reforms, fundamental liberties and social justice and backed by massive and regular demonstrations by the people.

It seemed that the Brotherhood had the upper hand and within the context of democratic reforms, the actions and decisions of Scaf would be scrutinised for consistency with the basic principles of democratic governance.

Yielding the executive prerogatives of the president and posing as the guardian of the interests of the people, the Scaf abrogated the 1971 constitution and replaced it with a Constitutional Declaration, giving itself significant legislative power and limiting parliament’s powers to drafting and amending legislation.

Scaf represented “the state domestically and abroad, signed international treaties and agreements” without the need for parliamentary ratification.

The position of the Brotherhood was considerably strengthened when it and the Salafist parties won a majority of parliamentary seats in the 2011-2012 legislative elections.

The Scaf issued a new Constitutional Declaration, as an addendum to the one issued in March, 2011, giving themselves additional powers. For instance, they granted themselves full control over military matters, including the prerogative to declare war. Further, the Scaf can form a Constituent Assembly and veto provisions in the new constitution. Significantly, the Scaf reportedly intends to continue its role in the present form, establishing itself as an independent source of power escaping accountability to elected civilians.

On June 14, 2012, the High Constitutional Court (HCC) declared the Parliamentary Electoral Law unconstitutional and the Scaf dissolved the entire elected assembly.

The arbitrariness of these decisions, with little input from the people — the original source of legitimacy in a democracy — suggests that the generals are reluctant to submit to civilian authority — the hallmark of democratic governance. For almost 60 years the military has been in power, shielded from the oversight of any civilian authority. The January 25 revolution presented the military with an opportunity to entrench its power in these uncertain times and it yielded to the temptation.

Still, there is a chance that the military might hand over all powers to the president and emerge as the defender of the acqui revolutionaire.

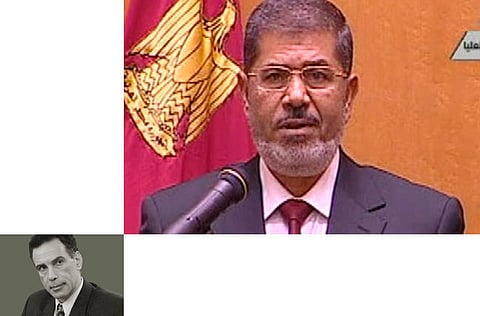

Last Friday, Mohammad Mursi took the presidential oath in Tahrir Square before thousands of protesters demanding that the military hand over power to the president elected by the people.

Mohammad Al Assar, a member of Scaf, reportedly said president-elect Mursi would have full presidential powers when he takes office.

Despite a constant struggle for power, it is precisely this handing over of power, the peaceful transition from one contender to another, from one administration to another, that regularly put democracy to the test. Democracy is about, among other things, majority rule, minority rights, liberty and equality before the law.

Crucially, democracy is about government on the basis of the consent of the governed.

The functioning of democracy is based on the tacit acceptance of the rules of the game. When popular consent is withheld, the defeated party peacefully hands over power to the party that has just been invested with popular consent to govern on behalf of the people.

In this respect, the news that Ahmad Shafiq — who lost the presidential election to the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mursi — had sent Mursi a telegram congratulating him for his victory, it was a small but significant affirmation of the rules of democratic governance.

Adel Safty is Distinguished Visiting Professor and Special Advisor to the Rector at the Siberian Academy of Public Administration, Russia. His book, ‘Might Over Right’, is endorsed by Noam Chomsky and published in England by Garnet, 2009.