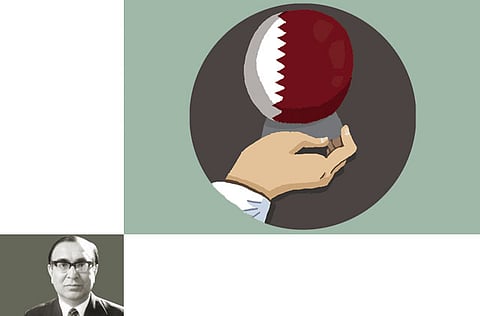

Qatar tries to untangle Afghan knot

For Pakistan, a peaceful neighbour and a quiet shared border are essential elements in its strategy for survival

There is some light at the end of the tunnel and the source of that ray of hope is Qatar. It is here in the capital of a small state with an ever expanding diplomatic footprint that reliable contacts with the Taliban are becoming available to the mighty armies — 90,000 American troops partnered by another 50,000 Nato and allied forces — that now seek a favourable end to a decade-long war they have not been able to win. It is highly meaningful that the weary international community is turning to an Arab state to salvage some pride and enough strategic advantage to justify a huge expense in blood and treasure.

On its part, Qatar may dispense with its recent larger-than-life style in influencing the outcome of uprisings in Libya and Syria and make a more modest beginning to untangle the Afghan knot, snarled badly by the hubris of the coalition’s military hawks. It will have to start more as a venue where the elusive Taliban provide an accessible address than a proactive mediator, at least for now.

There will be good reasons for such restraint. This has been a war in which the ideologues of the Bush era sought physical extermination of Al Qaida and their alleged accomplices, the Taliban. Negotiating with an enemy that you did not just want to defeat but obliterate is a formidable task; it is courageous on Qatar’s part to help build an environment where the peace process could begin. Secondly, the raison d’etre of the conflict has not stood the test of time. Christened the global war on terror, it acquired overtones of a clash of civilisations and, occasionally, even of faiths. Confronted with military stalemate, the hawks explained failure by postulating the equally untenable construct of an extended AfPak region.

Complex conflict

In Pakistan, this formulation was seen as an excuse to create a larger battlefield. The insurgents had, admittedly, support from kindred tribal communities on the Pakistani side; their bonds forged closer during the jihad against the Soviet Union. This time Pakistan was seen as an ally of alien invaders and the Pakistani component of anti-western forces — the Tehrik-e-Taliban-e Pakistan (the Taliban Movement in Pakistan) — wreaked horrible vengeance leaving the Pakistani state perceptibly weakened.

Ironically, in devising the end game, the American public diplomacy tends to oversimplify the complex conflict in Afghanistan as a contention between Kabul and Islamabad. Pakistan was ruled out as a possible venue for contacts with the Taliban because of the fear that it would influence them. Turkey was mentioned and then forgotten as an alternative. The choice of Qatar was marred by intelligence leaks to the media that President Hamid Karzai and the Pakistan establishment were being deliberately relegated to minor roles.

Karzai was, indeed, apprehensive that it would marginalise his High Council for Peace. Pakistan has a vital stake in Afghanistan’s future as it has a 2,500-km-long border with it. So it has reached out to Qatar and initiated an intensive bilateral dialogue with Karzai’s government. Following a visit to Kabul by Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, Hina Rabbani Khar, Islamabad hopes to receive Karzai later in February. Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad will probably join a trilateral review of the regional situation on February 18.

Pakistan has resolved to assist the Qatar process as well as the efforts of the Afghan High Council as it desperately wants an end to hostilities. It has, however no illusions. Substantive negotiations with the Taliban and their allies like the Haqqani group that has a strong presence in the eastern provinces of Afghanistan are not going to be easy, particularly if the US continues to seek permanent military bases on Afghan soil. Washington has harped on the need to fight and talk simultaneously. This includes death squads of Special Forces that kill mid-level Taliban commanders, making it very difficult for their supreme leaders to make significant concessions.

The Nato-US war plans are increasingly uncertain. Shaken by the killing of four French soldiers by a regular Afghan infantry man, President Nicolas Sarkozy plans to pull out the French contingent by mid-2013. The stir created by this decision has been raised to seismic level by US Defence Secretary Leon Panetta’s statement in Brussels that American troops would end combat duties also by mid-2013, well before the promised end-2014. Subsequent clarification that he only meant the termination of “lead combat role” has helped only partially.

Against this backdrop, Taliban leadership may wind up its terms. Even when peace is agreed upon in principle, there would still be the question of modalities, such as the existing constitution, free and fair elections, agreement on the stationing of troops and guarantees on the rights of women highlighted as a major western objective.

The Qatar process would be greatly jeopardised if Iran is attacked by Israel or hobbled beyond endurance by US-inspired international sanctions. So far as Pakistan is concerned, peace in Afghanistan and on its shared border is an essential element in its own strategy for survival. This would, doubtless, be its principal brief in the forthcoming talks with the presidents of Afghanistan and Iran.

Tanvir Ahmad Khan is a former foreign secretary and ambassador of Pakistan.