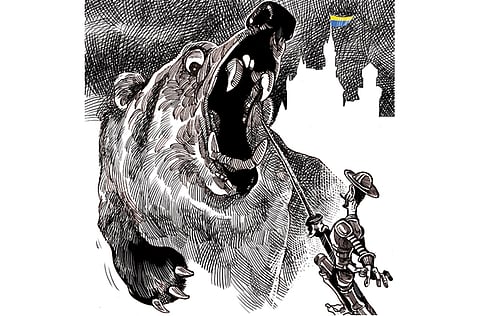

Punishing Russia is a fool’s errand

For Ukraine to have a future, Russia’s interests will have to be accommodated

Washington is abuzz with talk of a containment strategy to deter a newly aggressive Russia and punish it for challenging the post-Cold War European order with its seizure of Crimea. Advocates point out that similar strategies succeeded in undermining the Soviet Union and bringing Iran to the negotiating table. No matter that success came after more than 40 years in the first case and a dozen in the second, following the Iran non-proliferation act of 2000. Containment is a strategy for the long term, for at least as long as Russian President Vladimir Putin remains in power. It will not work. Nor will it advance US interests.

Economically, Russia is impossible to isolate. It is the world’s sixth-largest economy and a leading exporter of hydrocarbons, providing the European Union with a third of its oil and gas. While the White House promised further western sanctions last Friday, the big emerging economies have no intention of isolating Russia. None supported the recent United Nations General Assembly resolution condemning Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Politically, the US lacks the power and authority to persuade or compel others, including its Nato allies, to follow its lead in cutting Russia off. Americans are exhausted after a decade of unsuccessful warfare. Europeans, focused on internal problems, are likewise not prepared to make sacrifices to contain Russia; certainly not over Ukraine.

More importantly, containment will not serve America’s interests. The US no longer operates in a bipolar or unipolar world, in which it might have been possible and at times sensible to isolate Moscow. No matter how objectionable the US may find Russia’s recent behaviour, on some matters it will need its cooperation — non-proliferation and counterterrorism now; managing relations with China in the future.

In the Ukraine crisis, America has two objectives. The first is to stabilise the situation in Ukraine and deter Russia from seeking further territorial gains. The second is to defend the principles underpinning today’s European order. To achieve these goals, Washington needs to approach Moscow with a mixture of focused resistance and calculated accommodation.

Resistance to Russian aggression should guide America’s strategy. The credibility of Nato’s Article 5 commitment to collective defence should be reinforced, both to reassure exposed allies and to deter Russia. Military exercises, air patrols, contingency planning and similar activities in support of Poland and the Baltic states are necessary. Over the longer term, Nato allies need to rebuild the military capabilities that have been eroded over the past generation.

However, resistance alone will not suffice. Sanctions may demonstrate America’s outrage, but they have done little to deter Russia and they will not solve Ukraine’s problems. The country is broken and its state is going broke. State power has withered away across the country since the revolution in Kiev, revealing deep political fissures between regions. Ukraine’s inability to launch a respectable security operation against the rebellion in the east reveals how unreliable its military and security forces have become. All the while, Ukraine teeters on the edge of fiscal collapse. Even without Russian interference, Kiev will face a monumental task in rebuilding the Ukrainian state, forging a national consensus and repairing the economy.

This task cannot be accomplished without Moscow’s cooperation. Russia supplies the bulk of Ukraine’s oil and gas. It accounts for a third of Ukraine’s trade and unlike Europe provides a market for its manufactured goods. Historical ties, personal networks and ethnic identity give Russia considerable leverage over Ukraine’s internal politics. Moreover, Moscow is prepared to spend vastly more than the US and Europe to advance its goals in Ukraine because — unlike western powers — it believes the country is vital to its security. For Ukraine to have a future, Russia’s interests will have to be accommodated to some degree.

The outlines of an accommodation are already visible: Non-bloc status for Ukraine; decentralisation of the country’s political institutions; some kind of official status for the Russian language and an economic package drawing on US, European and Russian resources. Kiev is proposing constitutional reform that acknowledges those Russian concerns. Now is the time to begin negotiating the details.

That is where the US should be focusing its energies, instead of trying to find new ways to contain Russia. Only active American participation, along with moral and material support for Kiev, can produce an equitable negotiated settlement.

The Ukraine that emerges will not be the western-oriented one that Washington wants. Moscow will wield significant influence. The struggle over Ukraine’s geopolitical orientation will not end, but it will take a back seat to political competition in Ukraine. That will not be a bad outcome.

— Financial Times

Thomas Graham was senior director for Russia on the US National Security Council staff from 2004 to 2007.