Parents, and not schools, can work miracles with children

Family has an advantage: Advice is easier to swallow from someone in the same boat than from an official lecture

This is a tale of two boys that may have a universal appeal. Jack is 15, casually racking up detentions and in danger of flunking his grades. Tharush is the same age, but sits conscientiously doing extra maths on a Friday night while his classmates are out partying. But it’s also, at least in part, a tale of two parenting styles. Jack’s mum seems lovely but works long hours, and can’t face a long row over the homework he doesn’t do when she gets home. Tharush’s mum escaped civil war in Sri Lanka by stowing away in a container for 18 hours, afraid she would die, and is now determined her boy should make the most of chances she didn’t have. Jack moved in with Tharush’s stricter parents while his equally disengaged classmate Hollie went to live with the school’s head girl and her family, who enjoy challenging each other to name Shakespeare plays over supper.

Spoiler alert of a recent BBC programme on children: After six weeks of early bedtimes, beadily supervised homework and other wholesome activities, both guinea pigs’ scores on a maths paper improved. Bonus question, for an extra five marks: Discuss what, if anything, that proves.

Strictly speaking, of course, it wasn’t meant to prove anything, but merely to dramatise what decades of rather more rigorous research shows — namely the extraordinarily powerful influence of parental involvement on children’s attainment. It’s debatable how much is nature or nurture, and which precise bits of parenting make a difference. But there’s a broad consensus around the usefulness of things such as reading to small children, setting routines and boundaries, ensuring teenagers get enough sleep, eating dinner together, and showing you take schoolwork seriously.

Obviously, that’s infinitely easier if a parent’s own life is comfortable and unstressed; you try emulating the Waltons while simultaneously being evicted from a rented flat, or hiding from a violent ex, or even being too exhausted by your newborn to prise the iPad from its older sibling’s hands.

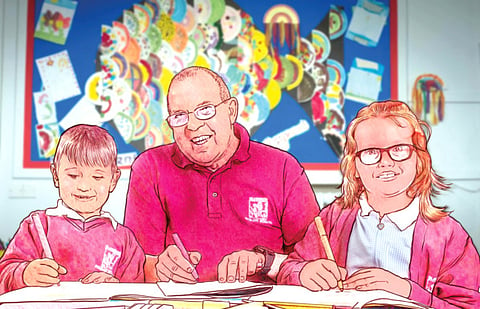

But beyond the extremes are plenty of children like Jack and Hollie who aren’t traumatised or on the breadline but hover on the borderline of a pass or fail, and could be doing better. That’s the territory explored by a new wave of education telly that also includes Britain’s Channel 4’s Class of Mum and Dad — about a group of parents sent back to primary school — and Indian Summer School, following five struggling British boys packed off to a strict overseas boarding school. All three are a reminder that home environments, and what they mean for expectations of schools, are curiously under-discussed.

On the right of politics, any suggestion that teachers can’t be expected both to teach and simultaneously compensate for anything missing at home is rejected as the bigotry of soft expectations. Liberals, meanwhile, worry about sounding judgemental or snobby, even though self-indulgent parenting transcends class divides: Think of the pushy private school parent who can’t believe their little darling’s D-grade might be his own fault for not revising, and blames the teachers instead of pondering his work ethic.

But talk to teachers, and you hear about the endless time spent parenting the parents, never mind the children: Breaking up fights between grown adults in the playground, explaining that it’s probably best not to let children stay up till 3am, playing Xbox, or instantly take their side in every dispute. We are expecting schools to solve problems created at home while simultaneously cutting the very things — from early intervention projects to children’s mental health services — that might help. If politicians want educational standards to keep rising inexorably that means investing in family life, too.

State intervention in parenting has an admittedly chequered history. Sure Start is the standout example of focusing on children’s early development while tacitly recognising how much of that flows from helping parents parent; but in some neighbourhoods, it was colonised by parents who didn’t need it, and results could be patchy. Former British prime minister David Cameron’s troubled families programme was overhyped, underfunded and presented unnecessarily confrontationally by politicians as punishment for “bad” parents, although on the ground, it did some decent work in places. The longer school days introduced by inner-city academies, so pupils could do homework in school supervised by teachers, were a practical recognition that for some, school is the only relatively quiet, safe place they know, but there’s a limit to how long they can be on the premises.

There’s no silver bullet. In some cases it will be about lifting financial stress on families, in others about changing behaviour — including supporting those parents who are doing their best who desperately want to help their children, but struggle with the legacy of their own schooldays. The TV show Class of Mum and Dad was full of them — from the dad who kicked instantly against the rules to the woman who fled a maths test designed for 11-year-olds in tears because she couldn’t do it, and turned out to have been bullied as a child. It left you wondering why routes back into adult education aren’t better-linked with schools when wanting to be able to help with your own child’s homework is such a powerful motivator. Could schools become gateways to life-long learning, offering refresher sessions after hours to parents unfamiliar with the bus-stop method for division (ask an eight-year-old) or even night classes leading to qualifications?

The surprisingly good-natured exchanges between Jack and Hollie’s parents and their host families, and the friendships forged between the children, hint, meanwhile, at the importance of peer mentoring. Advice is easier to swallow from someone in the same boat than from an official lecture.

But the final step in other cases is parents ourselves taking responsibility for what we do or don’t do: Recognising that schools can’t work miracles, that blaming teachers for things beyond their control is unfair and demoralising. It’s time this debate moved off the telly and into real life.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist.