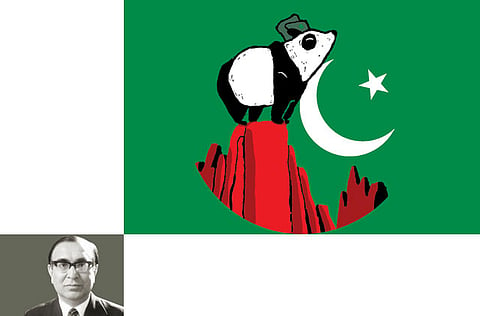

Pakistan's China connection

Islamabad has understood Beijing's new obligations as a world power and adjusted its strategic expectations

Pakistan’s main diplomatic effort at present is directed at stabilising its troubled relationship with the US. Prone to fluctuations, relations between these partners in the war on terror have touched a new low recently. As in the past, a lively debate has sprung up about whether Pakistan is playing the China card to offset western pressure.

More or less, the same questions surface again and again: Will China stand by Pakistan in a real crisis in which the US and India figure singly or jointly? Can China ever replace the US as a source of economic assistance? Does Beijing have the hardware needed by Pakistani armed forces? Wouldn’t China feel discomfited by a problematic regional ally in its own pursuit of global objectives?

Specific contents of this seemingly motivated analysis can be easily summarised. One, Pakistan exaggerates its strategic relations with China to gain diplomatic leverage. Two, their relations have been eroded by militants threatening Xinjiang’s peace. Three, China cannot take over the burden of economic assistance for Pakistan from the US. Four, some analysts, mostly in India, express concern about the increasing Chinese presence in Pakistan’s Northern Areas. A National Defence University (Arlington) study entitled Emerging Strains in the Entente Cordiale by Isaac B. Kardon and The New York Times recent write-up entitled “Pakistan learning that China’s friendship has limits” are examples, respectively in the academic and media domains, of bleak forecasts. Indian sources repeatedly allege that thousands of soldiers of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) are working on dual purpose projects in Gilgit-Baltistan. Powerful sections of the international media carry de rigueur, sensational reports about Sino-Pakistan collaboration in nuclear and missile technology. Pakistani and Chinese observers are often baffled by these contradictory narratives.

A basic distinction seems to have informed Pakistan’s two most important relationships. Pakistan entered into military pacts with the US in 1950s and the vectors of their interaction have largely been determined by the strategic demands of the vastly more powerful partner. It has essentially been a transactional relationship with rewards for Pakistan dependent upon delivery and performance. Accordingly, the trajectory has seen generous assistance, especially to Pakistan’s military, during the highs alternating with decades of sanctions arising out of Washington’s tendency to revert to coercive diplomacy during the lows.

Pakistan turned to China earnestly in 1962 and found it a kindred ‘third world’ country totally free of the hubris of Great Powers. Since then China has become a global economic player and a major voice in the political realm. While the assumptions of 1960s are no longer valid, this extraordinary ascent to China’s enhanced status has been conducted, in Pakistan’s case, with deep mutual understanding. Pakistan has understood China’s new obligations as a world power and adjusted its strategic expectations. On their part, the Chinese have reiterated time and again that their support for Pakistan within the mutually agreed parameters remains undiminished. To assert that the relationship has limits is a tautology; all inter-state arrangements are subject to mutually envisioned parameters.

What does this vital connection signify at this moment? Pakistan and China forged a special nexus when India and the Soviet Union had adversarial relations with China. India is now a major trading partner of China; the latter builds on this foundation despite the unresolved border issue partly because it is a hedge against India committing itself fully to the American project of turning it into a hostile counter-weight to China. Beijing maintains robust defence cooperation with Pakistan, including the joint production of an advanced fighter plane, while using every opportunity to remind Islamabad that it should pursue the policy of detente and eventual rapprochement with New Delhi. China is now close to Russia, and Pakistan is using all possible means, including Beijing’s mediation, to establish profitable ties with Moscow. Having played a key role in facilitating a dialogue between China and the US, Islamabad has never looked at its bilateral relations with these two giants as an either/or situation. It recognises that these are distinct subsets, neither of them a substitute for the other.

This distinction is particularly evident in the economic field. Beijing is not in the business of acquiring client states and it has always aimed at assisting Pakistan in building its own capacity. China has an edge over the US in popular esteem because it has visible monuments — the Gwadar port, the nuclear power reactors, the spectacular Karakoram highway to China now being upgraded, the heavy mechanical complex near Islamabad — to show for this policy. Bilateral trade has not found an optimal level largely because of a severe downturn in Pakistan’s economy and China is participating in special measures being taken to redress this situation.

Meanwhile, the Chinese soldiers work with Pakistanis on an increasing number of infra-structure projects that would also enable China to use Pakistan as a gateway to the Middle East and Africa. China remains Pakistan’s only source for nuclear power production. Neither country considers some imagined great game as the context of bilateral relations. Describing their relations as a unique ‘brotherhood’, both work avowedly in enduring trust.

Tanvir Ahmad Khan is a former ambassador and foreign secretary of Pakistan.