Obama’s UK trip comes at a critical time

With the referendum debate on a knife edge, Cameron sees the US president’s intervention as positive

US President Barack Obama makes his final trip to the United Kingdom as president tomorrow.

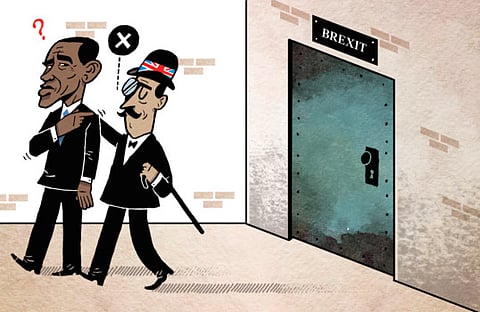

While the visit which continues until Saturday has a wide-ranging agenda, including renewing the international fight against Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), it is Obama’s support for Britain remaining in the European Union (EU) that will attract most attention and controversy.

With the UK population currently appearing split down the middle over the wisdom of continued EU membership, more than 100 MPs have signed an open letter requesting that Obama “not interfere in the domestic political affairs” of Britain. London Mayor Boris Johnson, the most high-profile campaigner for Brexit, has gone further by highlighting what he sees as the “outrageous and exorbitant hypocrisy” of Obama’s interventions in the EU referendum noting that “it is plainly hypocritical for America to urge us to sacrifice control — of our laws, our sovereignty, our money and our democracy — when they would not dream of ever doing the same”.

In this context, US and British officials are cautious about how the president makes his pro-EU pitch, and Obama will temper his remarks by emphasising that the decision must ultimately be one for UK voters. However, at a time when the referendum debate could be on a knife edge, UK Prime Minister David Cameron believes that the positives of the president’s intervention outweigh the negatives.

British people, in general, have significant respect for Obama, certainly compared to his presidential predecessor George W. Bush, as research from Pew Global shows. Since Obama’s election in 2008, for instance, favourability of the UK population toward the United States has increased significantly from some 53 per cent to 65 per cent today, and more than three quarters (76 per cent) of the British population has confidence that the president “will do the right thing regarding world affairs”.

So it is clear that Obama will have upside influence with some voters, potentially including the young who tend to be the most pro-EU, but the least likely to actually turnout to vote. Hence the reason why there will be a London ‘town hall’-style event with young people during the trip.

Obama’s visit thus comes at a potentially critical moment in Britain’s post-war history. For decades, two key pillars of UK foreign policy have been membership of the EU, plus the importance of the so-called special relationship with the US.

These pillars are inter-related and the fact that the UK may now be on the verge of Brexit is concerning many in the US. For while some on the right of the US political spectrum, including former UN ambassador John Bolton, favour Britain leaving the EU, there is generally strong bipartisan support in Washington for London remaining in the Brussels club.

Stronger partner

In turn, this reflects the fact that US policy during the post-war period has generally been one of support for European integration. Embodied in President John Kennedy’s 1962 Atlantic Partnership speech, US administrations have tended to believe that this made future wars in the continent less likely; created a stronger partner for the US in meeting the challenges posed by Moscow; and enabled a more vibrant market for building transatlantic prosperity. While US attitudes toward European integration have become more ambivalent as the process deepened, especially under the Bush administration, Obama has repeatedly expressed his wish for a “strong Europe”.

And the key reasons for long-standing US support for the UK remaining in Europe centre around the fact that London’s core interests and values are perceived by many US decision makers to — in general — more closely approximate those of Washington’s than any other European partner. As Damon Wilson, a former member of Bush’s National Security Council, asserted recently in congressional testimony, Brexit would deprive the US “of a critical voice in shaping not only EU policy, but the future of Europe”.

So there are genuine concerns in the US over how Brexit would weaken and disrupt the currently-28 EU member state’s balance of power, inner workings, and policy orientations. Take the economy, for instance, where the UK has long played a major role in conceiving and pushing forward initiatives such as the European Single Market, and been a significant influence for open markets, freer trade, and a less dirigiste approach.

In the words of Senator Ben Cardin, the ranking Democrat on the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, Brexit would “weaken Europe dramatically, and it could lead it to disintegrate”. And these worries are reflected in the longstanding position of the Obama administration that “the US values a strong UK in a strong EU, which makes critical contributions to peace, prosperity, and security in Europe and around the world”.

To reinforce this message in recent weeks, several senior US officials including Secretary of State John Kerry, Trade Representative Michael Froman, and former CIA director David Petraeus have made their own interventions in the debate. On the security front, for instance, Petraeus has argued “none of the problems the US and UK face will become easier to solve if the UK is out of the EU; on the contrary, I fear that a Brexit would only make our world even more dangerous and difficult to manage”.

Meanwhile, Froman has asserted that “Britain has a greater voice at the trade table being part of the EU, being part of a larger economic entity”, and has also pointed to the positive impact of the Single Market for UK and US prosperity. Moreover, he has, controversially, appeared to rule out a US trade deal with Britain if it leaves the EU, warning that UK firms could face major tariffs to enter the US market.

Taken overall, the president’s visit comes at a potentially critical moment in Britain’s post-war history with the prospect of Brexit. His intervention in the referendum debate will provoke controversy, but given the major stakes in play, and the fact that the debate appears on a knife edge, it is a calculated risk that both Cameron and Obama believe is worth making.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.