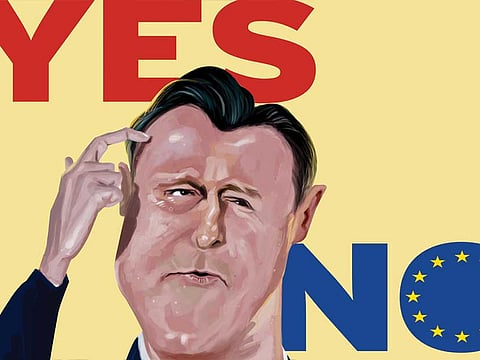

No easy choice for UK on its EU future

The political calculation is that voters will grasp the idea that Britain has set itself apart, but this misses the fact that if it strikes out on its own it can have full command of its destiny

The coming referendum on Britain’s place in Europe invites a choice between an unavoidably uncomfortable future and comforting nostalgia for a more predictable past. This collision of realism with emotion sets the quest for security and prosperity in a world that no longer belongs to the West against hankering for the days when Britain made the global rules.

The choice is not readily distilled for the ballot paper. Prime Minister David Cameron’s government intends to reframe it with the promise of a “new deal” for Britain in a “reformed” union. Europe’s perennial outlier, the prime minister’s pitch has it, can hold on to the benefits of membership while exempting itself from the integrationist ambitions of its partners. A favoured phrase in Downing Street these days is “the best of both worlds”.

Cameron has told fellow leaders he would like an agreement by the end of the year. The date for the plebiscite has yet to be fixed, but he wants to keep open the option of late spring or early summer 2016. That means striking a deal at the December Brussels summit. British officials describe this timetable as demanding but achievable.

An accord has been made more possible by Cameron’s willingness to retreat from what were once pivotal demands — “full-on treaty change” and restrictions on the free movement of people across the union. On the first of these, Britain would now be content with a protocol modelled on that given to the Copenhagen government after Danish voters repudiated the Maastricht treaty in 1992.

Such an agreement would be binding on the other 27 European Union (EU) states, and, where necessary, its provisions would be incorporated into the EU treaties when they were next renegotiated. As regards free movement, the British goal has been revised to restrict in-work benefits for those arriving from other EU states. Both of these look like plausible, if not easy, ambitions.

Negotiations are picking up pace. Cameron’s latest meetings with Francois Hollande, the French president, and Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor, have been accompanied by a great deal of diplomatic paddling below the water. The British side admits, though, it has been reluctant to set down any details in formal texts. Officials fear that, like many other secret EU documents, they would quickly find their way to the Financial Times’ Brussels editor Peter Spiegel.

Cameron, who has all but bet his premiership on securing a ‘Yes’ in the referendum, plans a second round of bilateral talks with each and every one of his EU counterparts. He will add a rare excursion to Strasbourg to put his case directly to the European parliament. By some estimates, Whitehall has had more contact with EU parliamentarians during the past six months than during the preceding 10 years.

As for substance, the British demands now fall into four baskets. The first covers a general exhortation that the union should be more competitive — extending the single market, scrapping needless regulation and such like. Some would say this is motherhood and apple pie. The second is about drawing clearer lines between members of the euro and those who have kept their own currencies; or, more specifically, guarantees that the former will not ride roughshod over the latter and so damage the City of London. A third deals with the vexed question of in-work benefits for EU nationals in Britain. The fourth would allow national parliaments to apply a brake to Brussels legislation, for greater subsidiarity and, very specific to Britain, for an opt-out from the notional EU goal of ever-closer union.

Wish list

There is no guarantee of a deal. Merkel, Hollande and the rest have one or two other things on their minds — Syria, a refugee crisis and Russian role in Ukraine among them. Greece could destabilise the euro again at any moment. These other leaders, as they have doubtless told Cameron, also have domestic political constituencies to satisfy. For all the diplomacy, things will get tougher once the wish list begins to be translated into legal texts. All that said, the others scarcely want to see Britain leave. The Germans, as former chancellor Konrad Adenauer once said, do not like the idea of being left alone with the French. The feeling is reciprocated in Paris.

Cameron’s strategy is clear enough. Wrap up a modest package of concessions and the symbolic disavowal of ever-closer union with existing opt-outs from the euro, the Schengen open borders system and some judicial affairs, and he can claim that Britain has stepped off the fabled Franco-German locomotive of European integration. There is something in this, too, for its partners. Safe on the platform, London will no longer throw boulders on to the tracks if they choose to steam ahead.

The political calculation here is that, while voters may be oblivious to the detail of any package negotiated in Brussels, they will grasp the idea that Britain has set itself apart.

What this misses is the emotional force of the (duplicitous) claim that, if only it strikes out on its own, Britain can take back full command of its destiny. The clinching case for EU membership has always been the hard-headed assessment that, in a world in which power is shifting elsewhere, Britain’s interests are best safeguarded within the club. This is not the easiest of sells. But all the rest is window dressing.

— Financial Times