Nihon Hidankyo and the struggle for a nuclear-free world

Atom bomb survivors endured, but their pain and plea for peace must never be forgotten

On 11 October 2024, the Norwegian Nobel Committee made a timely and significant decision in awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Nihon Hidankyo, a Japanese grass roots organisation comprised of atom bomb survivors, or Hibakusha, from Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

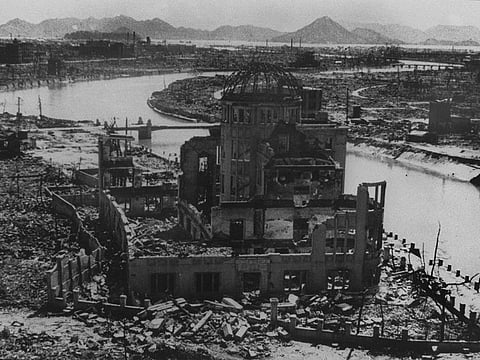

This award serves both as recognition of past suffering and as a stark warning for the present and future. Over the past 25 years, whenever I have travelled to Japan, I always make a trip to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum to remind myself of the horrors of war in general, and nuclear war in particular.

Nihon Hidankyo’s mission — to create a world free from nuclear weapons — is more relevant than ever as the world witnesses an alarming nuclear arms race.

The choice of Nihon Hidankyo resonates deeply in today’s world, where nuclear threats loom larger and the global geopolitical landscape becomes increasingly unstable. In recent years, nuclear powers have expanded and modernised their arsenals, breaking a long-standing commitment to disarmament.

Nihon Hidankyo’s receipt of the Nobel Peace Prize serves as a reminder of the consequences of using these weapons and emphasises the need for collective action to avoid repeating the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The members of Nihon Hidankyo are no ordinary activists. They are the Hibakusha — survivors of the only nuclear attacks in history, when the United States dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. The bombings claimed the lives of over 120,000 people instantly, and many more succumbed to radiation poisoning, burns, and injuries in the following months and years. The survivors bore physical and emotional scars that would last a lifetime.

Also Read: Why Israel must respect multilateralism

Unified voice for bomb survivors

Instead of succumbing to bitterness, many of these survivors became vocal advocates for nuclear disarmament. Formed in 1956, Nihon Hidankyo emerged as a unified voice for atom bomb survivors in Japan. Their message is simple: the world must ensure that no one else ever experiences the horrors that they have lived through.

Through witness testimonies, educational campaigns, and global advocacy, the organisation has been instrumental in shaping public awareness of the catastrophic consequences of nuclear warfare.

Their experiences gave birth to what has come to be known as the “nuclear taboo” — the near-universal understanding that nuclear weapons should never again be used. For nearly 80 years, this taboo has largely held, but as geopolitical tensions rise and nuclear arsenals are expanded, that understanding is in danger of being undone.

Today, the threat of nuclear warfare is growing at an alarming rate. While the Cold War ended decades ago, the global disarmament efforts that followed are now being reversed. According to the Stockholm International Peace Institute (SIPRI), nine countries — the United States, Russia, China, the United Kingdom, France, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea — hold a combined total of over 12,000 nuclear warheads, many of them operational and ready for deployment.

A full-scale nuclear war

Russia and the United States together account for about 90% of the world’s stockpile, and both countries have been modernising and upgrading their arsenals at an unprecedented rate.

Nuclear diplomacy has also taken a blow. In February 2023, Russia suspended its participation in the New START treaty, the last major arms control agreement with the United States, and withdrew from the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) later that year.

This has signalled the beginning of a new and dangerous era of nuclear competition. China, too, has expanded its nuclear arsenal significantly, placing more warheads on operational alert than ever before. Other nuclear-armed nations are developing and deploying new types of warheads and delivery systems, increasing both the size and lethality of their arsenals.

Such developments are disturbing and place the future of global stability at great risk. As the Nobel Committee noted, nuclear weapons today are far more destructive than the bombs dropped on Japan in 1945. The use of even a fraction of these weapons would result in catastrophic loss of life, global environmental damage, and potentially irreversible impacts on the climate. A full-scale nuclear war could destroy human civilisation as we know it.

Awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Nihon Hidankyo is not only a tribute to the Hibakusha but a clarion call for the world to renew its commitment to nuclear disarmament. As the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki age, their personal testimonies of suffering and resilience serve as a powerful reminder of the stakes.

Horrors of nuclear war

Their stories bear witness to the indescribable horrors of nuclear war, and their ongoing activism highlights the pressing need for action.

Through their work, Nihon Hidankyo has shaped global movements advocating for a world free of nuclear weapons. In recent years, some progress has been made with the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), which entered into force in 2021. This treaty, signed by 94 nations, outright bans the development, testing, and use of nuclear weapons. However, none of the nine nuclear-armed states have signed or ratified it, making its impact largely symbolic so far.

As we approach the 80th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world must confront a sobering reality: the nuclear taboo is weakening. The very existence of nuclear weapons, their modernisation, and the growing willingness of world leaders to threaten their use represent a profound failure of international diplomacy and collective security.

World leaders must take heed of this message. Disarmament efforts must be prioritised, nuclear non-proliferation agreements must be reinforced, and new treaties aimed at the complete abolition of nuclear weapons must be pursued. Diplomacy and dialogue are the only viable paths toward ensuring that no city ever again suffers the fate of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In awarding the 2024 Nobel Peace Prize to Nihon Hidankyo, the Norwegian Nobel Committee has reminded us of our collective responsibility. The Hibakusha may not be with us forever, but their stories, their pain, and their calls for peace must never fade.