What does the new British government make of its war in Afghanistan? While we await a clear statement, events in the blighted country hurtle with their own menacing momentum towards the endgame. Two weeks ago in Washington, President Barack Obama tried to appease his increasingly intransigent Afghan ally, Hamid Karzai, who had recently threatened to join the Taliban.

Laden with reassurances and promises of some more cash, the Afghan president had barely arrived back in Kabul when the Taliban attacked a Nato convoy in the city. Within 24 hours of the suicide attack, which pushed the number of American soldiers killed in Afghanistan to 1,000, the Taliban assaulted the American base at Bagram. They were also reportedly in control of Marja in Helmand province, three months after being driven out by Nato and Afghan soldiers in an offensive. Another ambitious military campaign looms this summer, this time in Kandahar; and plenty of embedded journalists will be at hand to report on thrilling battles with, and early successes against, a treacherous enemy.

But the periodic trumpets of war in Afghanistan increasingly fail to drown out the dangerously deepening confusion at the heart of western strategy, especially as every few months a new enemy announces itself on an arc now expanding from Waziristan to Connecticut.

A car bomb in Times Square wasn't what Obama may have been expecting when, fulfilling his presidential campaign promise, he expanded the war on terror into north-west Pakistan.

Last year more soldiers and civilians died in this almost unnoticed new theatre of war than in Iraq and Afghanistan put together. It was also last year that the American-backed Pakistani assaults on the Taliban in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas turned an astounding three million people into refugees.

Many of them have since gone home, but hundreds of thousands are still homeless; a wave of retaliatory suicide-bombings across Pakistan, which has killed hundreds, demonstrated the depth of vengeful rage unleashed by the military operation.

However, this extraordinarily volatile situation will be briefly covered in the western media only when there is another terrorist attack on the West. Obama has declared that American forces will start withdrawing from Afghanistan in July next year, by which time they will have been fighting there for longer than they did in Vietnam. It will be politically expedient for him to wind down the war and bring a majority of soldiers home before the next presidential election in 2012. The timetable depends entirely on success in defeating or bribing the Taliban into passivity, which also makes it absurdly impractical.

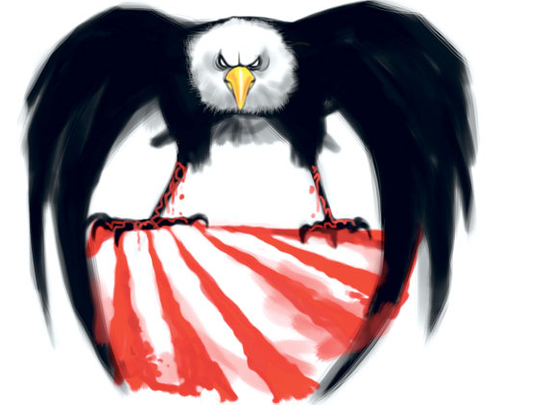

Meanwhile, as the civilian casualty rate declines in Afghanistan, it shoots up in north-west Pakistan. According to one recent estimate by Pakistani officials, the CIA's Predator drone strikes killed 700 civilians, the majority women and children, during Obama's first year in office.

A more conservative estimate last year by the New America Foundation puts civilian casualties at about 30 per cent of the total fatalities in these strikes. Obama has ramped up the killing spree, firing 18 missiles on May 10 alone. And the normalisation of these almost everyday massacres proceeds apace. Speaking early this month at the annual White House Correspondents Association dinner, Obama mock-threatened the boyband idolised by his daughters with these words: "Boys don't get any ideas. Two words for you: Predator drones. You will never see it coming".

The giggles, if any, had faded by later that evening as news of an attempted assault on New York's Times Square began to filter in. It's clear that a natural wannabe American was not only radicalised by the grisly spectacle, as Faisal Shahzad confessed to his interrogators, of "innocent people being hit by drones from above"; he also received help from those determined to strike back.

This blowback, and the mushrooming worldwide of many unlikely and reluctant fundamentalists, was widely predicted. And the ranks of the homicidally enraged will swell as long as the CIA and the Pentagon seek to achieve victory through an exalted capacity for murder and destruction.

For as the American writer James Baldwin, no counter-insurgency expert, wrote: "It is ultimately fatal to create too many victims. The victor can do nothing with these victims, for they do not belong to him but to the victims. They belong to the people he is fighting."

This desert of bewilderment is where the US and its allies find themselves today, almost a decade into their longest war in modern history; the new government faces no more urgent and daunting task than leading Britain out of it.

Pankaj Mishra is an Indian author and writer of literary and political essays.