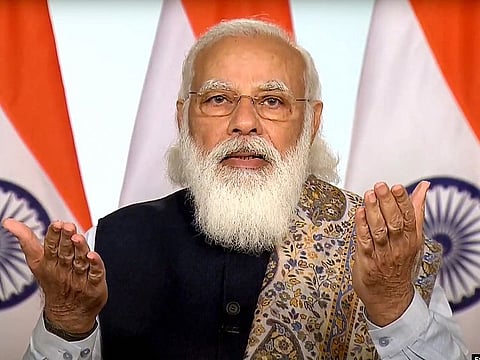

Here is another side of Modi’s Gujarat Model

BJP’s grip over society is not due of communal polarisation and Hindu nationalism alone

Also In This Package

It’s quite-often quoted that Gujarat is the laboratory of kind of Hindutva politics that the RSS wants to have it in India.

Since the BJP, under the leadership of Narendra Modi, has come to the centerstage of the national politics, displacing the Congress, the anti-BJP politics is defined oft times as fighting against the “Gujarat model”.

On April 12, West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee once again said that she won’t allow Bengal to be Gujarat. In Delhi, if the word secularism is much used and abused, “Gujarat” too is much sullied in the capital’s corridors by power elites since 2002 riots of Gujarat.

Still going strong

In the eyes of many anti-Modi critics, the state is anything but secular. In a convoluted way, the negative branding of Gujarat has helped Modi. Therefore what the opposition wants to use against him is actually working for the BJP.

Modi’s critics should try and decode fresh if it is only the politics of communalism and Hindu nationalism that is working in favour of the BJP? Or, are there more layers in the Gujarat model?

Why has Modi’s political roots in Gujarat remained strong even after seven years of leaving Gujarat?

In fact, the situation is quite undemocratic where you hear many people inside and outside the government saying that “amara CM PM che!” (Our chief minister is the Prime Minister!)

What works for Modi

Three fundamentals continue working for Modi even today when his home state — Gujarat — is in the middle of Covid mismanagement. Add to that the corruption level in the administration, which is all-time high. The struggles of the poorer classes have increased much more.

Modi’s connect with people has been a work in progress. He started experimenting with this blueprint to tie the people with his party since 1987.

Over the last few decades so many Gujaratis have expressed in different ways to me that the real Gujarat model is where the government ensures that the families in cities and towns feel safe and secure about their girls and their sons don’t have to visit police stations.

This desire sounds simplistic but it’s not. It’s about the difficult job of keeping the law and order situation in place. This desire of the parents is universal but in Gujarat, the political class, even the corrupt ones, takes it seriously. Gujarati-speaking Hindus and Muslims, both, have this instinct uppermost on their mind and there are clear visible attempts at the community level to help the parents.

Family matters

In 90s whenever non-Gujaratis visited Gujarat they would observe with curiosity teenage girls driving back home on two-wheelers at midnight. This desire of the family safety is, also, the Gujarat model. Most of the BJP and Congress MLAs would spend time and energy in their constituencies on the “family matters” that comes before them. It’s an important part of their political career.

Since 2014, Modi and Amit Shah are identifying same sociocultural instincts of the society in the voters of Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal.

2) In Gujarat, the BJP and the pre-1990 Congress had always respected that their voters are overwhelmed by consumerism — global phenomenon. Gujarati voters are demanding consumers, too. Also, the centrality of money is accepted in Gujarat brazenly. In last 20 years not many social uprisings have taken place in spite of miseries of the marginal classes because there is universal acceptance of the “Paiso bole che” (money speaks) dictum.

The middle-class Gujarati society, Hindus and Muslims both, demands certain necessities and comforts and if the state doesn’t come in their way to acquire it and provides necessary level of security, the anti-establishment sentiments in people remains low. The Ahmedabad riverfront on the banks of Sabarmati is criticised by many town-planners but the middle class of Ahmedabad is relishing it while giving credit to Modi.

It is impossible to ignore the grim reality of existing fault line between Hindus and Muslims in certain pockets of Gujarat but as Zafar Sareshwala, a community leader explains, “Like Gujarati Hindus, Ahmedabad’s Gujarati Muslims very much wanted the riverfront and the BRT road systems in the Muslim-dominated areas and they got it.”

3) Since the early 90s, the BJP has been engaging with the big and small sects in every districts of Gujarat. Like the hundreds of the milk and sugar cooperative societies Gujaratis- Hindus and Muslims alike are quite apt and much ahead in nurturing and managing the faith-based sects that boasts of the multibillion rupees efficiently-run-economy of their own. These sects are one of the most vital parts of the family life of Gujaratis. Not just Lord Shiva, Ram and Krishna but the importance of the sub-sects and various Goddesses Shakti peeths cannot be underestimated.

The Swaminarayan sect and Vaishnavite Bhakti sects are among the richest and enjoy huge following. The pilgrimage places at Somanth, Dwarka, Nadiyad’s Sant Maharaj and Dakor have millions of followers.

Millions of devoted followers

Gayatri pariwar and Morari Bapu who read Ramayan have hundreds of thousands of followers. Most of them run schools, colleges and many other social services. The BJP has live contacts with the Gujarat-based Islamic sects, too. Modi and Amit Shah have the most cordial of relations with all prominent religious leaders and supports their activities overtly. The infrastructure development of these pilgrimage centres speaks about the role of the BJP in it.

Since more than two generations, small-town BJP leaders have been working hard to connect with these sects. Congressmen have lost badly in keeping the connect they had for decades. Congress leader Arjun Modhawadia says, “We don’t have network with them now. Some of the managers work under pressure of the BJP. But we need to introspect, too, how and why we lost it.”

Achyut Yagnik, co-author of The Shaping of Modern Gujarat: Plurality, Hindutva, and Beyond says, “It is not the BJP alone that has played the part in Hindutvasation of Gujarat’s middle class. The various sects of Hindu religion too have played a major role in spreading the assertive Hindutva identity.”

In Gujarat the BJP’s story will remain incomplete without understanding the role of these sects in the society. It is a story of three decades during which the BJP reached out to the devotees via these pilgrimage centres. In Kutch, the legendary temple of Ashapura Mata is revered by lakhs of devotees. BJP’s local leader and lawyer Pravinsinh Vadher is a member of the trust that runs it. He himself is the devotee of Ashapura Mata.

In fact, Bhupendrasinh Chudasama, state education minister, is the unofficial BJP nodal point for the last 20 years for all the sects. He is an affable leader and himself a religious man. If you meet him, it’s difficult to distinguish between the bhakt and politician inside him.