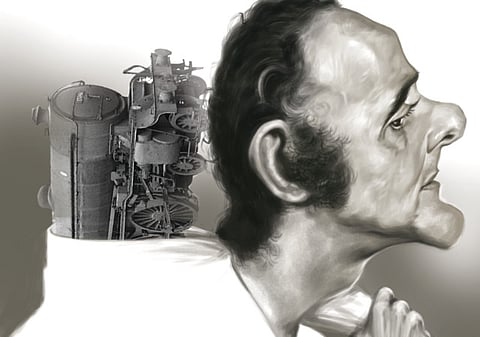

Criminal with a mythical air

Ronnie Biggs: The slippery customer

Perhaps the most flattering epitaph for Ronnie Biggs, who died aged 84, was written for him many years ago by the unlikely figure of the former commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Robert Mark. He observed in his memoirs that Biggs had “added a rare and welcome touch of humour to the history of crime”, and suggested that his time in Brazil meant that he was the most memorable figure to undergo banishment since Henry Bolingbroke, the future Henry IV, in 1398.

The most memorable part of Biggs’s life, of course, occurred on August 8, 1963, when he and a group of 16 fellow criminals robbed the Royal Mail, Glasgow to Euston night train of £2.6 million (Dh15.6 million) in a heist so audacious that it soon became known as the Great Train Robbery, and was to spawn books, films, records and legends.

Prior to that key moment in British criminal and legal history, Biggs had been going straight for three years, earning his living as a carpenter and builder with his own business in Reigate, Surrey. Born the youngest of five children into a working-class family in Lambeth, south London, he had had his first brushes with the law as a teenager during the Second World War, when he would rummage through bombed-out buildings and help himself to what he found.

Over the next few years, he was convicted nine times. A shoplifting offence took him to borstal for the first time, and although he joined the Royal Air Force in 1947, he was soon back behind bars after a break-in at a chemist’s shop. He was dishonourably discharged from the services.

Car theft led to a third sentence and it was during that period that he met Bruce Reynolds, the mastermind of the Great Train Robbery. It was Reynolds whom Biggs contacted when he wanted to borrow £500 in 1963, only to be asked if he would like to take part in “a job”.

Biggs said later that he asked for 24 hours to think about it, but made his decision in seconds. He helped recruit to the team a retired train driver whose windows he had been repairing. However, despite the attention to detail with which the robbery was executed, fatal errors soon led the police to the doors of most of those who had participated. Biggs was no exception, having left his fingerprints at the farmhouse where the gang had met to divide the money. Like his colleagues, he was jailed at the Old Bailey for 30 years, a sentence imposed as a draconian deterrent to such crimes, but one that contributed to the elevation of the robbers to mythic status and creating for them a sneaking public sympathy.

Not that Biggs stayed around to serve his time. In July 1965, he escaped from Wandsworth prison, “the hate factory” in south London, through the ingenious use of a rope ladder and a furniture lorry with a specially constructed turret that had been parked outside the jail. Two getaway cars were stationed nearby, and before the police realised what had happened, Biggs was in Paris. There, he had a plastic surgery, costing £40,000, to change his appearance and then fled to Australia — first to Adelaide and then to Melbourne. At the time, with a regular supply of British immigrants arriving in large numbers in Australia, Biggs was able to blend in well as “Terry Cook”, a carpenter — so well in fact that his wife, Charmian, was able to join him with his three sons.

Here was his chance to live a new life as a bronzed expat, but an article about the train robbers appeared in an Australian newspaper and one of his new acquaintances realised that his friend Terry was not so much a cook as a thief. Interpol was alerted, but once again Biggs was one step ahead, fleeing to Brazil, with his long-suffering wife’s blessing. It was a hard decision for him as it meant leaving not only Charmian but his three sons, Nicky, Christopher and Farley. The decision was made even harder for him when Nicky was killed in a car crash in 1971 and a grieving Biggs almost turned himself in. Later, he was to say of his criminal career: “I lost my family. I wasted my life.”

In 1974, he met a journalist from the Daily Express in Rio de Janeiro and agreed to an interview, unaware that the Express hierarchy in London was collaborating with Scotland Yard, helping them track down Biggs to his new lair. Detective Superintendent Jack Slipper flew to Brazil as part of the sting and greeted a surprised Biggs with the famous words: “It’s been a long time.”

But Biggs had not used up his nine lives. His Brazilian girlfriend Raimunda de Castro, an exotic dancer, was pregnant, and under Brazilian law, as the father of a Brazilian, he was granted immunity from deportation. Raimunda left for Switzerland when their child, Michael, was two, and Biggs brought the boy up alone. Raimunda and Biggs parted, although they married years later in Belmarsh prison. Michael became a pop star in Brazil in a band called the Magic Balloon Gang. Biggs himself had entered the music business briefly in 1978, recording No One Is Innocent with the Sex Pistols.

Attempts, official and unofficial, to bring him home continued. In 1981, a seedy trio of British ex-soldiers kidnapped him and hauled him off to Barbados with a view to bringing him back to the United Kingdom and selling the story and pictures. Once again, the law came down on Biggs’s side — Barbados sent him back to Brazil on the grounds that he had been illegally seized.

He continued to live off his notoriety, posing for photographs with tourists in exchange for money, selling souvenir T-shirts that commemorated his escapes, scrabbling for crumbs from the media table and charging tourists £40 for a barbecue at his house. In 1992, he advised visitors to the Earth Summit in Rio on how to avoid being mugged there.

In 1993, Slipper went out again, courtesy the Sunday Express, to try to persuade Biggs to come home voluntarily, but he was not ready to do so. He wrote his memoirs, Odd Man Out (1994) and seemed relatively content to be seeing out the end of his days in the sun. Old friends, including Reynolds, visited him in Brazil for his 70th birthday party in 1999.

But ill health changed his mind. A suicide attempt and a series of three strokes laid him low, so that by 2001, he was ready to submit himself to the British prison system he had fought for so long to escape.

His former companions had moved on or died. Buster Edwards had hanged himself, Charlie Wilson was shot dead in Spain, others had died of natural causes or, like Reynolds, finished their sentences and written their autobiographies. The figure that returned to England was a sorry sight, wearing a Sun T-shirt and in a wheelchair, despite the jaunty claim (invented by the Sun) that he fancied one final pint in Margate before he died.

A 1938, Jimmy Cagney film, Angels With Dirty Faces (one of Biggs’s own favourites), tells the story of a famous Brooklyn criminal, admired by young delinquents, who goes whimpering to the electric chair, pretending to be a coward so that he puts them off crime. It is tempting to think that when Biggs returned to England, humbled and looking sorry for himself, that he was merely doing a Cagney. But the reality is that he feared he was dying and was unable to get the treatment he needed in Brazil. Michael loyally accompanied his father back, although he said he had tried to dissuade him many times from returning because he did not want him to die in prison.

Back in jail once more, Biggs’s health deteriorated. He married Raimunda Rothen, as she had by then become, in 2002.

Michael continued to campaign, Biggs’s lawyers attempted to have him freed on compassionate grounds, and by 2009 it was widely expected that he would be granted parole, following a fall and further hospitalisation. But the then justice secretary, Jack Straw, refused his release, principally because he had shown “no remorse for his crimes nor respect for the punishments given to him”. Biggs went back into hospital with severe pneumonia and Straw decided that since he was not expected to recover, he could be released on compassionate grounds. By then, he was barely able to talk or move. He reappeared, still unable to speak, for the launch of his updated memoirs, Odd Man Out: The Last Straw, in November 2011.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Ronald Arthur Biggs, robber and fugitive, born August 8, 1929; died 18 December 2013.