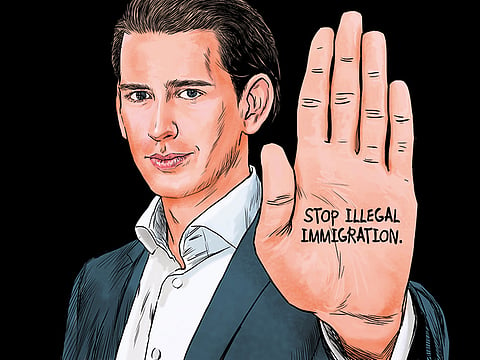

Conservative revival in Austria has a message for Europe

Kurz took a lead in the elections by getting to grips with immigration

The dramatic victory of Sebastian Kurz in the Austrian election will send shock waves across Europe. The dashing new chancellor is a political prodigy: not only because he is just 31, but because he is leading a mainstream conservative party into territory previously dominated by the far-right.

Exit polls say his People’s Party has emerged as the clear winner and will probably form a new coalition with the populist Freedom Party and its leader Heinz-Christian Strache, whom Kurz has deftly outflanked. Still, this means that Austrians have elected their most right-wing government since Hitler’s Anschluss in 1938.

Does this mean a return to the politics of the Thirties, or even to the Eighties, when the former UN secretary-general Kurt Waldheim was elected Austrian president, despite having hidden his Nazi past? Certainly not: having interviewed Waldheim at the time, I am confident that Kurz has nothing in common with his lies and evasions, still less with the anti-Semitism that his election stirred up.

But Strache, who will probably now be vice-chancellor, once joined a neo-Nazi youth organisation and his party has a dubious record. Kurz will therefore need to stamp his authority on his coalition partners from the outset. He promises to impose tough new restrictions on refugees and economic migrants to ensure that Austria is never again overwhelmed by an influx on the scale of two years ago. He is thereby breaking with the cosy liberal establishment that has dominated politics in Vienna for decades, but has also seen off the far-right.

The reason for Kurz’s ascent can be put in two words: border anxiety. Austrians have seen themselves as Europe’s sentinels since the Ottoman Turks were stopped at the gates of Vienna in 1683. They are at once cosmopolitan in culture and nationalist in politics. Austria was happy to adopt coffee from the Turks, but some forces in the country remain deeply suspicious of political Islam. There is a new ban on the burqa and niqab in the country.

Border anxiety

Having embraced the EU’s freedom of movement and even the open borders of the Schengen Agreement, Austria suffered a rude awakening in 2015 when German Chancellor Angela Merkel welcomed more than a million migrants into Europe, most of them via Vienna. Not for the first time, Austrians felt boxed in by decisions made in Berlin. As foreign minister, Kurz saw his chance to speak for a nation gripped by border anxiety — and he seized it. This tale from the Vienna woods could be replicated in other parts of the continent.

Everywhere the same pressures from uncontrolled migration are making themselves felt: on housing, on public services, on security. Such pressures will only grow as tens of millions of migrants from Africa and Asia head to Europe over the next decade. And so everywhere mainstream leaders have been repositioning themselves to see off populist challenges, from Mark Rutte in The Netherlands to Emmanuel Macron in France.

Conservatives who ignore border anxiety are doomed to lose power to the populists, as Merkel now knows to her cost. Last month’s election has left her ruling coalition in tatters. A new anti-immigrant party now has 94 seats in the Bundestag. It calls itself Alternative for Germany, but the truth is that Germany now has no alternative but to guard its borders.

What does all this mean for the British Prime Minister Theresa May? Immigration may have been curiously absent from the last election. Yet border anxiety lies behind all these issues, too. The Grenfell Tower disaster shone a light into the dark recesses of London’s own migration crisis. Unless the government not only delivers Brexit but puts in place robust controls to allay border anxiety, the Tories will lose power — perhaps for a generation.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2017