Britain is right on how to take refugees

Cameron’s policy makes better sense, but the problem is that he is not going to take in enough of those in need of new homes fast enough

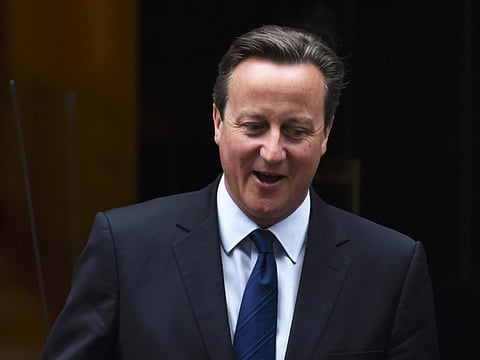

British Prime Minister David Cameron has taken a battering over his handling of Europe’s refugee crisis, but in one respect — offering to open the door to those who have not yet made it to Europe, rather than those who have — he is right and his European critics are wrong. Cameron on Monday set out his new approach — let’s call it the Aylan Kurdi policy, after the drowned Syrian toddler whose harrowing photograph forced Britain’s leader to reverse his previous, and frankly shameful, zero-tolerance line on refugees. In a statement to parliament, Cameron said Britain will now resettle as many as 20,000 from refugees from camps around Syria during the next four-and-a-half years. This resettlement programme already existed, but until now it was a transparent ruse to accept as few refugees as possible: Just 216 Syrians since March 2014.

At the same time, Cameron restated his refusal to take part in the European Commission’s Germany-led plan for a quota system to redistribute those refugees who have already reached the European Union (EU). Last Sunday, former Italian prime minister Romano Prodi became just the latest European figure to lecture Cameron on this, warning that he will face retaliation for his ungenerous stance when he asks leaders for help with the EU reforms he needs to win a referendum on whether the United Kingdom should stay in the bloc.

These threats are misplaced. It is in the interests of the rest of the EU that the UK should remain part of it. To invite a Brexit because of Cameron’s refusal to toe the line on refugees would be idiocy. And redistribution is, in any case, not a solution to the underlying refugee problem: It would not, for example, have saved Aylan. Redistributing refugees around the EU in a rational way is necessary triage, given the numbers that arrived on the shores of Greece and Italy this year. But it became necessary only because countries including Germany and the UK failed to do the right thing previously.

Meaningful resettlement

A combination of the 1951 Refugee Convention and the unwillingness of European nations to consider asylum applications from Syrians located in third countries — such as Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey — means that the only option for refugees languishing in camps is to pay smugglers to get them to Europe. As soon as they touch EU soil, their rights under the convention kick in.

One way or another, refugees will come to Europe because they are unable to build lives in their overburdened host countries. If a meaningful resettlement programme existed, they could wait in line in Amman, Beirut or Gaziantep for relocation, rather than risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean.

The infrastructure for such a programme exists. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) already has a system under which it vetted 104,000 refugees deemed most in need of resettlement last year. The UNHCR estimates that about 1.15 million actually qualify, some 8 per cent of the world’s total refugee population. Unfortunately, relatively few countries take part in the programme and last year they accepted only 80,000 applicants (21,000 of them Syrian). This, for example, is how the UK’s 216 resettled Syrians got into Britain. The UNHCR is explicit in saying that it vets only 100,000 of those in need, because there is no chance of persuading recipient countries to accept more.

The UK, as Cameron rightly boasted, has been among the most generous nations — second only to the US — in providing financial aid to Syrian refugees in the region. Some of those countries lecturing him have done much less. Yet, the offer to absorb 20,000 refugees by 2020 is hardly heroic, when the crisis is at its most acute right now. Germany may take hundreds of thousands of people this year alone and is appropriating an extra 6 billion euros (Dh24.64 billion) to do so. France on Monday agreed to relocate 24,000 of those already in Europe by 2017.

The problem is not that the UK is refusing to join the Commission’s solution of redistributing refugees around Europe. Indeed, Cameron’s policy makes better fundamental sense. The problem is that he isn’t going to take in enough of those in need of new homes fast enough to make a difference.

— Washington Post