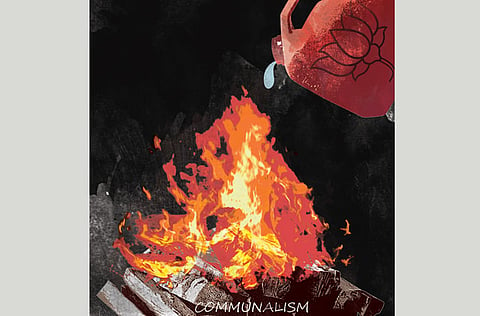

BJP has not given up on communal politics

BJP’s realisation of the futility of temple politics is not a permanent affair

Today marks the 20th anniversary of the Babri Masjid’s demolition in Ayodhya, India.

To understand why extremist Hindu groups demolished the mosque on December 6, 1992, it is necessary to go back to 1984. In that year, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which was then only four years old, reached the lowest point of its brief political life since it could win only two Lok Sabha seats.

In view of the drubbing, the then party president, Atal Behari Vajpayee, wondered at a national executive meeting in Calcutta (now Kolkata) whether it was a mistake to merge the erstwhile Jana Sangh with the Janata Party in 1977.

The reason for the musing was obvious. After losing its earlier identity and while trying to acquire a new one, the BJP had become neither fish nor fowl — to use (apologetically) non-vegetarian nomenclature. It was deemed imperative, therefore, for the party to recover what it had lost.

The BJP did not revert to the Jana Sangh where the name was concerned, but it did embrace what used to distinguish the Jana Sangh from other parties (except those on the Hindu right like the Hindu Mahasabha and the Shiv Sena) — its anti-Muslim outlook. But the BJP didn’t do so immediately, perhaps because of Vajpayee’s moderate beliefs.

It remained for the time being a votary of the vacuous ideology of Gandhian socialism. However, it relied on the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), which is the right of the BJP, to float the idea of ‘liberating’ the presumed birthplace of the Hindu deity Ram in Ayodhya where the Mughal emperor Babur (1526-30) had built a mosque in 1528.

It is worth recalling that throughout their history, neither the Jana Sangh nor the BJP had raised this issue earlier. It did not feature in the Jana Sangh’s election manifestos from 1952 to 1984, suggesting that the party was not such an avid devotee of Ram as it now pretends to be.

It was only in 1985 that the VHP raised the issue and it took the BJP four more years to endorse its stand. Again, the reason is patent enough. Having seen in 1984 that politics will lead it nowhere, the BJP plumped energetically for communalism.

There is a disturbing precedent of this tactic in Indian history. When the Muslim League realised after the 1937 elections that it had no chance of politically wresting power from the Congress, Jinnah turned to Muslim communalism to do the trick, just as the BJP under L.K. Advani turned to Hindu communalism.

If the League’s slogan was ‘Islam khatre mein hai’ (Islam is in danger)”, the BJP’s was that Hinduism was under threat — as it had been, according to the Hindutva camp, ever since the Muslims entered India in the ninth century.

This cultivation of the minority temperament was not the only feature of the BJP’s new brand of politics. It also adopted the medieval practice of demolishing the places of worship of its purported enemies. In fact, the BJP chose this destructive trait as a political ploy, being the only party in the modern period after the Nazis to attack the sacred precincts of its adversaries.

Not so subtle message

Apart from the Babri Masjid, the Hindutva group targeted two other mosques in Varanasi and Mathura. Significantly, Advani and Murli Monohar Joshi set out from these two towns to join the saffron storm-troopers in Ayodhya in December 1992 to send a not so subtle message to their fanatical followers. The Sangh Parivar’s slogan of the time, ‘Teen nahin teen hazar, nahin rehegi ek mazar, sought to whip up anti-Muslim sentiments by threatening to demolish as many mosques as possible.

The destruction of the “ocular provocation” of the Babri Masjid — in Advani’s words — did serve a purpose for the Hindu lobby. Just as the League achieved its objective of partitioning India by fomenting communal sentiments, the BJP succeeded in fulfilling its hitherto utopian dream of coming to power at the centre.

But, then, its ascent began to peter out. The BJP realised early enough that communalism was not a paying proposition when it had to shelve its pro-Hindu agenda in order to cobble together a coalition government in 1998. The coalition, too, started to fall apart after the 2002 Gujarat riots.

It will be a mistake, however, to think that the BJP’s realisation of the futility of communal politics is a permanent affair. If the opportunity presents itself — say, via an increase in fundamentalism in India’s neighbourhood — the party will again revert to its earlier policy of poisoning Hindu-Muslim relations.

All that can be said, however, is that a large section of the Hindus has understood the game of fraudulent religiosity which the BJP and the Parivar had played — and is still playing as the call given by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) for building the Ayodhya temple shows.

Amulya Ganguli is a political analyst