Afghanistan situation is a security challenge for Pakistan

A peaceful Afghanistan serves everyone in the region, but will it go that way?

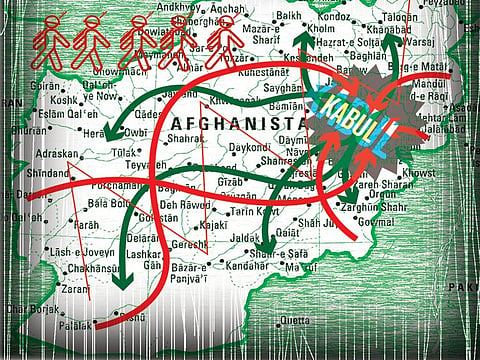

As the US forces withdraw from Afghanistan, leaving behind skeletal footprint, a couple of thousand contractors and some aerial capability to temporarily combat escalating violence, anxieties are rising in Pakistan about the shape of things to come.

It is not as if Islamabad wanted US forces to never leave the war-torn country. Pakistan has consistently stated that a stable Afghanistan that can decide its own future through an inclusive government is an ideal goal to achieve. Foreign forces, even if sanctioned by the United Nations resolutions, do not create an enabling environment for that purpose.

However, the swiftness with which the US decided and then executed the pullout has created a parlous situation that heightens fears in Islamabad.

For one thing, Kabul government relied heavily on international coalition support to hold on to power and to implement its writ in core parts of the country.

While violence remained endemic all around and thousands lost their lives in bombings and attacks, the government could function by paying bills and salaries to its staff and press into service state institutions.

All but collapsed ground opposition

When threatened with opposition attacks it could muster critical kinetic support, both aerial and ground, and ward off the challenge. For another thing, with US forces withdrawing, that mechanism of managing government and ground opposition has all but collapsed.

Washington and its allies have also pulled out technical advisers, whose expertise, if nothing else, was a source of guidance and a bridge to connect with the western capitals. If there is extreme uncertainty that rules the echelons of power in Afghanistan, it is understandable because the keystone of support is now gone.

This very fact is enough to spread worries around Afghanistan’s near-abroad, pretty much across Central Asia, much of South Asia and Indo-China lands, besides Europe via Russia.

Weak or weakened governments can precipitate multiple challenges, the most critical of which is the inability of the outside world to know who to deal with in times of urgent diplomatic needs.

Pakistan hopes that the Kabul government is able to ride the luck of a negotiated settlement about the future of Afghanistan and that the US is able to make the Taliban stick to the deal that assures a reasonable and reasoned terms of peace to end decades-old war in Afghanistan. But reality rebels against these hopes.

Shift in balance of power

The Taliban land gains are impressive and the momentum of their march now looks unstoppable. Not a day passes without news of towns and important districts falling to them as government forces abandon posts and vacate areas they once held with grit and at a great cost. This shift in the balance of power can create its own challenges, from revenge killings to larger concerns of civil war.

Being geographically contiguous, Pakistan cannot escape the blowback of such a development. While the border between the two countries is being fenced, it is a race against both time and history to bet on barbed wires blocking flocks of refugees coming Pakistan’s way.

Tribes straddling the border have a special genius for beating official restrictions and there are a hundred ways to move to and fro between the two countries. As a chronic host to two generations of refugees, from the 1980s to the 1990s, Pakistan’s hospitality is already exhausted.

Deep concern in Islamabad

Prime Minister Imran Khan has stated his intent to close the borders in case of a new influx into Pakistan. How practical such a block will be remains to be seen but it highlights how deeply concerned Islamabad is about the spillover of Afghanistan’s troubles into its own land.

Also, myriad groups intending to destabilise the country can thrive if border areas fall into a state of flux and confusion. This itself can stretch national resources and security forces to their maximum limit.

Also, statistics show that Afghanistan’s instability translates into more drugs and more guns smuggled into and across Pakistan, which has its own domestic and regional complications. For all these reasons, if Pakistan sees the Afghanistan situation as their security challenge number one at present, they are not wrong.

Conversely, a stable and well-managed Afghanistan holds immense prospects of bringing in regional prosperity and promoting harmony. For now, however, the odds of Afghanistan settling down are very low. The months ahead look grim.

Syed Talat Hussain is a prominent Pakistani journalist and writer. Twitter: @TalatHussain12