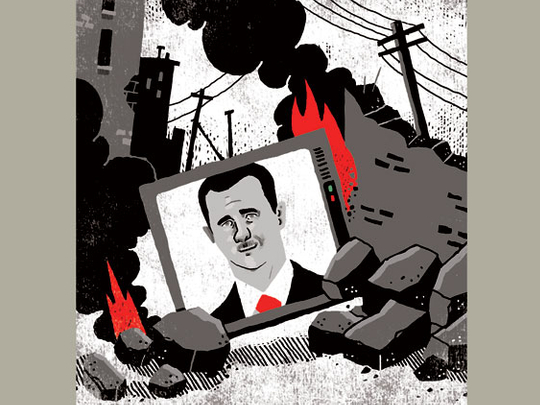

As the Syrian Army resumes its military offensive around Damascus, in Homs and in the south of the country, President Bashar Al Assad appears to be brushing up his international image in a diplomatic offensive designed to rehabilitate both himself and the regime.

Al Assad has recently given a series of interviews to foreign media outlets, impeccably tailored and exuding statesman-like calm. On Thursday, he told Turkey’s private Halk TV station that he would stand for a third term in next year’s presidential elections, making no mention of the civil war raging across the country, the three million Syrians who have fled the violence or the 100,000 lives it has cost to date.

Paradoxically, Al Assad’s demeanour and self-confidence, however inappropriate, is one of few stable features in Syria’s turbulent, constantly changing political landscape; a landscape characterised by internecine violence and proxy power battles between foreign sponsors which are tearing the opposition apart.

Al Qaida-linked global jihadists now account for at least half of the armed opposition, but many of these fighters are battling the Free Syrian Army (FSA) for territory and engaging in bloody shootouts with Kurdish groups in the north.

Now, it seems, the Islamists are also fighting each other. On Thursday, the Saudis announced the formation of ‘the Army of Islam’, an umbrella organisation of more than 40 Islamist opposition factions inside Syria, aimed at counteracting the growing influence of Al Qaida affiliate, the Islamic State of Iraq and Al Sham (ISIS). The umbrella group includes Syria’s own homegrown Al Qaida affiliate, the Jabhat Al Nusra.

The Saudi initiative in its current form is unlikely to assuage western fears of an extremist takeover and takes the opposition even further away from the preferred western model of a united, secular-led national council capable of forming an alternative government.

Foreign powers’ concerns over the extremist element within the Syrian opposition have provoked a round of diplomatic musical chairs resulting in unanticipated new alliances, many of which benefit Al Assad.

Foremost among these is the rapprochement between the US and Russia, formerly at odds over Syria. Having stepped back from the brink of military intervention, US President Barack Obama has succumbed to Russian diplomacy and endorsed the Moscow-sponsored UN resolution which will see Syria scrap its capacity for manufacturing chemical weapons by November 1 and destroy all its stockpiles by mid-2014. Having dropped its primary insistence on regime change in Damascus, Washington now appears to be nearer Moscow over Syria than to its former (anti-Al Assad) partners in Paris, Ankara, Riyadh and Doha.

An additional, and unexpected, factor in the regional political equation is the apparent willingness of Iran’s new President Hassan Rouhani, to engage in diplomacy with the US. This also increases the likelihood of a negotiated settlement on Syria in which Tehran will now, probably, participate.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon announced last week that he expects the long-awaited Geneva II peace conference on Syria to take place in mid-November. The question is, who will sit at the table? The only certainty here is ... Al Assad’s regime.

Ban met with Ahmad Al Jarba, the Saudi-sponsored president of the National Coalition for the Syrian Opposition Forces (SNC) last week to discuss the matter. Jarba, who divides his time between Riyadh and Istanbul, committed to ‘reaching out’ to other opposition groups and claimed he could put together a united delegation for Geneva. Such optimism is, I feel, sadly misplaced.

The leader of the FSA, Salim Idriss, has already categorically stated that his organisation will not attend the talks. Rejecting the US-Russia disarmament deal, Idriss says the FSA will continue to fight until Al Assad falls and is tried for war crimes. Who then will speak for the armed opposition? Will the jihadists be invited to the table?

The SNC itself is largely discredited. At the end of last year, it enjoyed the support of 114 nations (the ‘Friends of Syria’) and the SNC took the national seat at the Arab League summit in Doha. Just six months later, however, the number of ‘Friends’ had dropped to less than a dozen, reflecting widespread disillusionment with the ability of the SNC to form a national unity interim government.

Nor does the regime accept the SNC as representative of the opposition. Syrian Foreign Minister, Walid Al Mua’alem, speaking on the fringes of the UN General Assembly last week, said it would not negotiate with the SNC because its leadership is based abroad.

As conflict and divisions continue to plague the opposition, and as external diplomacy gains more traction in the resolution of the Syrian crisis, the region’s cards are being reshuffled.

Syria appears likely to commit to destroying its chemical weapons in a bid to rehabilitate the regime and Iran, too, is entering a new phase of pragmatism and compromise which may well affect its nuclear policy. If Israel does not follow suit and agree to limit its nuclear and chemical weapons capabilities, it will find itself increasingly isolated within the international community and even at odds with its main sponsor, the US.

Meanwhile, in the absence of a credible, united opposition, a negotiated settlement brokered by international diplomacy may produce a result in Syria that would have been unthinkable even a month ago - that of Al Assad remaining in power, with the tacit support of the US.

He who laughs last laughs loudest.

Abdel Bari Atwan is the former editor of the pan-Arab newspaper Al Quds Al Arabi. His latest book is After Bin Laden: Al Qaida, the Next Generation.