A stable Libya is in Europe’s interest

The world seems blind to what is going on in Sub-Saharan Africa and absurdly optimistic

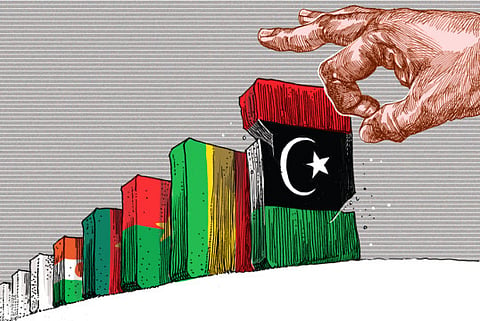

It is dangerous to assume that the fragile stability of Libya and the sub-Saharan Sahel region can continue to hold without more active nurturing from the international community. It would be very easy for the entire region to slip into chaos similar to Iraq and Syria, with dramatic consequences for Europe and the North African Arab states.

The international community seems almost wilfully blind to what is going on and absurdly optimistic about the various peace talks in very troubled states that look almost certain to fail. The most obvious case is what is happening in Libya, where a UN-sponsored peace process seems to rely on hope, but another case is northern Nigeria and Cameroon, where the Boko Haram terrorists still retain their grip on large swathes of country.

Egypt is particularly worried about the continuing civil war in Libya, as it shares a long border and many economic links. Hence, President Abdul Fattah Al Sissi is particularly voluble on the need to intervene on the side of the nationalists. Otherwise, he fears, the conflict may continue indefinitely and the chaos may then seep back into Egypt.

Key to stability

Libya is the key to restabilising the region. The fall of Muammar Gaddafi triggered both an exodus of the mercenaries that he had hired back to their African states where further violence followed, like in the breakaway region of northern Mali. Since then, the civil war in Libya has generated powerfully-armed militias, which are usually viewed from the perspective of the contest between Benghazi and Tripoli on the Mediterranean coast, with little reference to the deep south of the country where tribal militias hold untroubled sway. These tribal forces have every chance to link up with insurgent groups across the Sahel if they want to. This could easily lead to region-to-region alliances that could be very damaging. For example, if a small local radical group in Nigeria or Burkino Faso combines with southern Libyans’ military skills.

It may be that the final days of unfortunate Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan saw more action against Boko Haram as South African and other advisers have finally taken a more active role in getting Nigeria’s military into action and the new President Muhammadu Buhari looks set to take a more determined stand. But the terrorist group still controls large areas and continues to kidnap and bomb at will.

The 2012 civil war in Mali is one example of what can easily happen again. The entire north of the country was taken from the government and dominated by Tawareq separatists supported by ex-Gaddafi mercenaries, before they gave way to their Al Qaida allies. The French army intervened and defeated the insurgent alliance in 2013, but foolish government action restarted the war, which was only recently stopped by a treaty between the government and six insurgent groups in February 2015.

Yet more talks

Libya is currently going through another round of UN-sponsored talks with a June deadline that is hard to imagine will lead to any conclusion, even though many efforts have been made to plan out an agreed route to stability. Former prime minister Ali Tarhouni is the head of the constituent assembly and he told Gulf News in Davos this January that he had won broad agreement from all factions for the draft constitution, so that it is now ready to be used as a road map whenever it is needed.

UN Special Representative for Libya, Bernardino Leon, spoke at the recent World Economic Forum on the Middle East in Jordan and urged the parties to stop the violence. He said the dialogue represented an important opportunity for Libyans to stop the bloodshed and end their suffering and he called “on the parties to be flexible, to be generous, to be ready to make concessions. They cannot get everything, that’s obvious. Or they will not get enough. In which case, they may well think that it is better to continue in the current situation. I hope this will not be the case”.

When Leon was accused of being wildly optimistic, he readily agreed, quoting Winston Churchill that “I am an optimist. It does not seem too much use being anything else”. It is to be hoped that Libya’s warring factions agree with Leon as his plan is based on a constitutional settlement, but there is not much else, like an international carrot in the form of a vast European commitment packed to help destabilise the state.

Financial aid may seem out of place in an oil-rich nation like Libya, but the chaos of the civil war has made it difficult to find the initial money to start any normalisation. In time, the Europeans will need to recognise that the flood of refugees heading their way across the Mediterranean Sea will only stop when Libya is at peace, which is one incentive for the European Union to agree to a plan to send financial aid and technical and military support to the eventual interim government.