How to set up a child with autism to succeed

Be aware of the challenges the child faces and their needs

When our children are young, one of our biggest jobs is to advocate for them. As they get older, however, it’s important for them to take on some of that responsibility.

“I’m not going to always be here,” said Sharon Fuentes, a blogger in Northern Virginia and the mother of a boy with Asperger’s syndrome. “My main goal in life, for any child, is to raise an independent, responsible adult who is able to function in the world and be able to contribute to society. We all have to advocate for ourselves.”

So what steps should parents take? “First, the child needs to be aware,” said Fuentes, co-author of The Don’t Freak Out Guide to Parenting Kids With Asperger’s.

Once children with autism are armed with information about their specific challenges, they can advocate for themselves. But often, they lack the ability to filter how much they share, and with whom. So in addition to teaching them how to speak up for themselves, it’s important to make sure they know there are times when they might want to keep information private, said Jim Ball, the executive chairman for the national board of the Autism Society.

Here are suggestions from Ball and Fuentes on teaching your child when and how to disclose a diagnosis, and how to express what she needs:

Make sure children understand the difference between needs and preferences. Before she could teach her son, Jay (she uses an alias for him on her blog to protect his privacy, and we are using that name here), to go to teachers or administrators and ask for what he needed, Fuentes had to teach him that there is a difference between things he absolutely must have and things he would like to have.

Have older children write a note to their teachers. Fuentes got a template from ImDetermined.org before the school year started and had Jay use it to write a letter to each of his teachers. The letter outlined who he is, what he likes and dislikes, what stresses him out and what he needs to succeed. Jay handed the notes to the teachers himself before the school year started. “It was huge for teachers to see that,” Fuentes said. “It wasn’t just the mother saying this is what my son needs.”

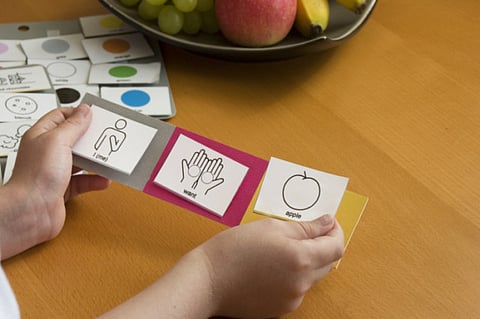

Include the child in Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meetings. Jay has begun sitting in for parts of his individualised education plan meetings, and Fuentes said it has helped him understand how things work and why he gets certain services or accommodations, but not others. It also allows him to voice concerns about situations that may be problematic for him. Not every child has the language skills to verbalise his/her needs, but Fuentes said that even a simple yes or no, verbally, through gestures or with an assistive communication device, can boost a child’s self-esteem.

Talk about “safe people” when it comes to sharing information. Talk to your child about when to share his/her needs or disclose his/her diagnosis, Fuentes said. Otherwise he/she might start telling other students, unnecessarily, and bullies could use the information against him/her.

“It’s a very fine line,” Fuentes said. “This is part of who he is. But I don’t walk around letting everyone know what my religion or sexual preference is. It’s the same thing. We are trying to teach him the parameters.”

Turn to a book. Ball likes Ask and Tell: Self-Advocacy and Disclosure for People on the Autism Spectrum, edited by Stephen Shore. Ball said it’s great for helping people get a grip on when to tell people about their diagnosis and when to keep the information private. The book has contributions from adults who have autism, including a preface by autism activist Temple Grandin. It uses a system of rules to teach people how to determine what information to share, and when.

— Washington Post