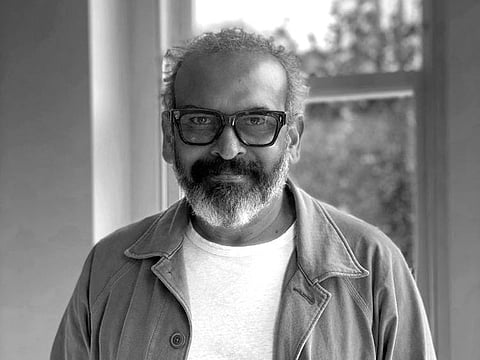

Getting to know renowned Indian artist Subodh Gupta

Artist has been creating installations of steel kitchen utensils for 20 years

A group of variously sized pots and pans glimmer. Some are silver while others appear to be brass or black painted steel. Their shiny texture beams with light making them seem almost glamorous objects despite their minimalistic qualities. The painted still-life is by one of India’s most renowned artists: Subodh Gupta. For over 20 years the artist has been creating large and small-scale installations of mass-produced steel kitchen utensils that are amassed together to create sculptures commenting on both personal and collective stories. Yet, over the last few years, the artist, who was trained as a painter, has been working more with paint on canvas. He kept painting the same subject matter—everyday objects that the artist uses to reflect on the social and economic realities of his Indian homeland while at the same time reflecting on various references from modern art.

Born in 1964 in Khagaul, a small town in Bihar, India, over the past few decades Gupta has become one of India’s most prominent artists. He is presently represented by galleries Nature Morte and Hauser & Wirth.

“I work with the old utensils and when you see the backside of the old utensils, every utensil as its own scratch, own marks,” said Gupta. “They look very similar to each other, but they have their own characteristics too and they’re very individual to each other, like a human palm. We all very similar to each other and then we have a line in every single palm that differentiates us like the marks on a utensil.”

Gupta’s works are also frequently accompanied by performances. At the beginning of this year, Gupta staged an exhibition at Le Bon Marché Rive Gauche in Paris titled Sangam (which means “confluence” in Hindi, referring to the confluence of three rivers, the Ganges, the Yamuna and the Saraswati), featuring 18 new sculptures comprised of everyday domestic elements—a signature of Gupta’s work. Also commissioned was Gupta’s Cooking for the World, a large installation of his work where he cooks and performs for all.

The artist says that sometimes he looks back on his installations and sees a constellation—a cosmos of sort as if despite their differences they were in harmony. “That’s how I find it. How come you can see the cosmos and in your words, within your plate, within your material, within what you’re working on it,” adds Gupta.

At Le Bon Marché, Gupta’s works were found scattered throughout the department store in a unique way that merged the store’s high-end products with the artist’s everyday utensil artworks. The dialogue was made between cooking utensils, art and shopping. There will be furniture and vintage objects wrapped in ropes in the shop windows, while an oversize traditional Indian pot and a giant bucket made of shiny aluminum kitchen utensils, out of which pours a shower of mirrors, will be housed under the skylights on either side of the escalators. And on the store’s second floor, there will be a hanging shack composed of vintage objects. The exhibition was the 8th show the high-end department show staged of works by a renown contemporary artist. Others included exhibitions by other prominent artists such as Ai Weiwei (Chinese), Joana Vasconcelos (Portugese) and Prune Nourry (French).

“Sangam is a cascade of mirror facets and sculptures made of domestic objects. It is an installation that questions the audience on their pilgrimage in a society focused on consumption,” Gupta explained in a statement at the time. “Le Bon Marché is where people from all over the world meet, encounter each other and form a human river.”

The works on show at the famous parisian department store, like Gupta’s new paintings, foster an opportunity to question the confluence or the crossroads at which we find ourselves. Works such as Gupta’s thus offer ways to contemplate both the personal and collective existence of daily life. Sangam, like artist’s other works, reflects the values of -intercultural dialogue—the belief that people from various cultures can come together through art. “Art can bring people together where language cannot,” says Gupta.

“I am painting a lot these days,” says the artist from his studio in New Delhi. “I trained as a painter event if I often work in sculpture. A sculpture takes two to three years to make. I make my paintings while also making and finishing my sculptures.” Its present still lifes, composed of simple kitchen utensil, also offer a sense of glamor and beauty. They shine on their own and and seem to stand tall and proud in their positioning on Gupta’s canvases—such simple inanimate objects that also retain such grace. “These utensils also remind you of your childhood upbringing,” notes Gupta. “What were the first utensils you used as a child? What was your first meal? What did it smell like?”

These everyday objects thus hold the key to myriad personal and collective recollections and that’s where their beauty and power can be found.