It's red-hot, Chile to China

The varied industrial applications of copper have made it a very desirable commodity, attracting investors along the way

The attributes of durability and versatility of the so-called red metal have been known for some time — for over 10,000 years in fact. Value might therefore naturally be attached.

Copper was the first mineral extracted from the earth by man. As an alloy with tin, it ushered in the Bronze Age, and a multitude of implements and weapons. Ancient Egyptians recognised its medical benefits, as did the Aztecs, using it to sterilise water and treat infections.

The Romans took the next step, using copper as money, later forming it into coins.

Fast-track to the current day and the metal's uses remain as varied as in ancient times, while its financial and industrial relevance as a commodity stand out.

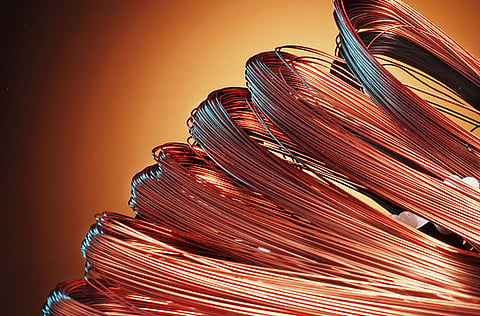

In 2010 more than 19 million metric tonnes of refined copper were used across a number of sectors globally. In the construction industry, its strength, malleability and resistance to corrosion make it useful in a broad range of building applications. The same goes for transportation. But it is the ability to conduct electricity that has meant its main industrial use (in fact 42 per cent of total use) is in the production of cable, wire and electrical products.

In addition, copper is one of the most environmentally-friendly metals, one of the few that does not degrade in the recycling process. The International Copper Study Group (ICSG) has estimated that 34 per cent of consumption in 2009 came from recycled copper. Adding to its green credentials, many energy-saving technologies such as solar power are all heavily reliant on the metal, owing to its superior conductivity.

High demand

No surprise, then, that it is in high demand and increasingly so. World consumption has almost tripled since 1970. And what's driving it? Robin Bhar, senior metals analyst at Credit Agricole, in a recent industry presentation gave the succinct response: ‘China, China and China'.

Indeed China accounted for 39 per cent (7 million tonnes) of global demand for refined copper last year compared with 28 per cent only two years prior to that, according to consultants CRU. The country's rapid industrialisation — in particular the surge in the country's power network — is behind this trend.

Some cyclical dip seems likely now. Most recently market decline has been associated with global economic turmoil.

According to the International Wrought Copper Council (IWCC), over the next two years demand is expected to slow to 8.4 per cent per annum, as against an average of 16.4 per cent between 2005-10, while China's demand is expected to increase by 7 per cent this year, down from double-digit growth in 2010.

The price of copper certainly felt the full force of the global economic crisis, falling off the proverbial cliff in 2008, but its ascent over the next two years was equally dramatic, until the latest setback.

Riding on the back of the faster-than-expected recovery in Asia, prices soared a staggering 250 per cent since the low in 2008, breaking through the $10,000 (Dh36,700) per tonne mark earlier this year, nearer $9,000 at time of writing.

While the price has drifted since then, the pointers are that further rises could be on the way. Analyst Bhar told Financial Review that global inventories are low compared to past cycles. At the end of last March the stock ratio was only four weeks against three months in the 1970s.

While not an issue in the seasonally low demand period over the summer, nevertheless later in the year the metal might reach new highs, subject to the world's fractured recovery. Taking a medium-term view, Bhar believes that between now and the time new supply comes on stream in 2014 the figure could reach $11,000 or more.

Supply source

So where is all this copper coming from that is being devoured? The answer, to a significant extent, is not dissimilar, phonetically — Chile. Of total global production last year of 16.1 million tonnes, Chile accounted for nearly 5.4 million tonnes.

The United States and Peru, next in line, produce in the region of 1.3 million tonnes. While new sources are out there — notably in Zambia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Siberia and Mongolia — exploitation is hampered by political instabilities and lack of infrastructure, resulting in higher extraction costs.

For Chile to increase supply isn't straightforward either. Capital expenditure was slashed in the downturn, and now, despite rising demand, funding is hard to come by. Additionally, many mines (including the world's largest, Escondida in Chile) are past their prime in terms of the ore extracted.Then there are short-term difficulties, such as the strikes in Chile. All of which combine to ensure that supply is going to lag demand for some time.

Supply-demand imbalances have attracted the interest of financial investors. In particular, the introduction of exchange traded products (ETPs), which allow an investor to trade a position in a commodity as easily as buying equities. Total assets held in commodity ETPs in total stood at $197 billion at the end of last April, according to Barclays Capital, obviously a hugely significant advance from just $16 billion at the end of 2006. Physically-backed ETPs, which remove stocks of the metal from the market, have helped to push up the price.

With prices propelled at such a rate, it is no wonder that end users of copper are looking for alternatives. Aluminium is reported to be taking share, particularly in low-voltage wiring and cable and commercial air conditioners. Credit Agricole's Bhar puts the potential substitution rate at around 5 per cent, with the view that its prospect has been overstated.

Thus, global inventories are low, demand high, and supply constrained. In the absence of a serious slowdown in the Asian economy, for the medium term copper looks set to resume a bull run, even if prices are themselves reddish for an interim.

GCC: Outlook for demand is strong

Urbanisation and infrastructure investment are driving demand for copper in most rapidly developing areas of the world, so it's no wonder that the International Copper Association's (ICA) president, Frank J. Kane, commented last year that the GCC is ‘‘a very important market".

Dubai International Financial Centre economists have identified the GCC, along with India, as the key centres of growth within Middle East, North Africa and South Asia (Menasa), with the value of projects planned or under way in the GCC at close to $2.9 trillion as of last April.

Against this backdrop the ICA, whose aim is to promote the increased use of copper, foresees the rise of the metal's consumption — at an annual rate of 600,000 tonnes — in the Gulf countries to about 6 million tonnes by 2020.

A key beneficiary of this demand is the region's manufacturers of copper cable. International companies such as the French giant Nexans, El Sewedy of Egypt(the region's leading producer), the large Saudi companies, and Ducab of the UAE have been increasing capacity in the region. In addition, a number of smaller players have entered the market.

The picture remains far from straightforward. New capacity and slowdown in some end-markets, such as construction, have resulted in oversupply in some areas.

In fact, according to a recent report by HSBC, "most of the cable operators in the GCC reported a net loss in 2010, stemming from falling gross margins". Naturally, the high copper price helps create that squeeze.

Speaking to Financial Review, Jessica Estefane, Assistant Vice-President at Shuaa Capital, pointedto the variety of factors involved. "It depends onthe market dynamics; power cables, especially on thelow- to medium-voltage segments, are highly-commoditised products with little differentiationbut price. So in the context of an oversupplied marketit is difficult to immediately pass on increasing copper prices to customers; a typical time lag would be ofabout three to six months. Of course, this depends onthe nature of the contract; most cable manufacturers try to sell their products at cost-plus, thus passing commodity risk entirely to customers at the time the contract is signed." Supply and demand rule, of course. "When demand overtakes supply [they] can pass on even more than the increase in the feedstock price to customers," she said.

Ducab, a joint venture between the Dubai and Abu Dhabi governments, says the volatility of copper's priceis effectively passed on at present. The company hasits eye on expansion. Already one of the biggest exporters to India (the world's fourth-largest cable market) of copper rods, Ducab is "keen to explore how to do more business" there. North Africa, Iraq and Iran are also on the radar.

The writer is a freelance journalist.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox