Francis Bacon in Your Blood review

In contrast to the bleakness of his art, this starry-eyed chronicle shows the painter could be genial, generous and waspishly funny

Francis Bacon in Your Blood

By Michael Peppiatt, Bloomsbury USA, 416 pages, $30

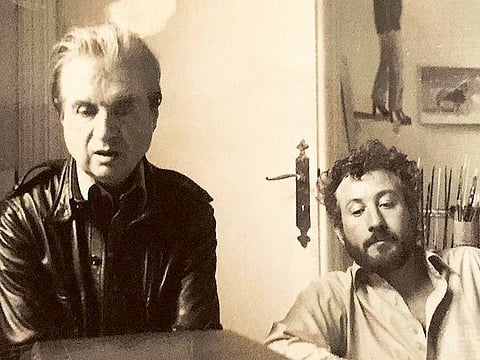

In the summer of 1963, exactly 200 years after James Boswell first met Dr Johnson, an impressionable young man named Michael Peppiatt was introduced to Francis Bacon in a Soho pub, the French House. It was a momentous occasion, for one of them at least. Peppiatt, a 21-year-old art history student at Cambridge, revered the painter, then (at 53) in the full flush of his talent, and was tickled to be taken under his capacious wing. He found himself not merely part of Bacon’s court on his noon-to-night jaunts around the fancy restaurants and louche drinking-dens of London but his chief confidant and protégé.

The photographer John Deakin, who had introduced them at “the French” that day, later remarked to Peppiatt: “It’s incredible, but you’ve become a sort of Boswell to Francis ... He talks to you about everything”. His advice is to “get it all down”, to be the painter’s amanuensis and thus ensure his own place in the mythology of Bacon’s “gilded gutter life”.

Peppiatt didn’t need telling twice. In the years since Bacon’s death in 1992 he has published five books about his hero, including a full-length biography, “Anatomy of an Enigma”, in 1996. One might have considered that a sufficiency, but here comes another, this one a memoir of their friendship over 30 years and a reckoning of Peppiatt’s own development in his mentor’s shadow.

The Boswell-Johnson analogy, however, now looks rather presumptuous. For one thing, Boswell — despite his buffoonery — was a superb writer even before he began the biography that was his life’s work (see his “London Journal”). For another, his subject was a brilliant talker whose wit and bons mots still crackle through the language.

On neither count can Peppiatt or Bacon remotely compare. “Francis Bacon in Your Blood” is partly a record of its subject’s table talk, which Peppiatt sets down as though recalling it verbatim. The strategy is a risky one. While Bacon was indisputably a great painter, his was not a great mind, and the deeper one reads into the book the more threadbare and repetitious its contents appear. His philosophy, if such it can be called, was one of devil-may-care nihilism, expressed in a few gnomic phrases: Life is ridiculous and futile. We come from nothing and return to nothing. Existence is a kind of charade. His “nervous system” is a “compost” from which his paintings emerge.

These same pronouncements keep coming around, until they take on an incantatory air. But they are hardly profound. At one point he admits, “half the time I don’t know what my painting’s about”.

It’s a telling moment: surely the greatness of Bacon’s work lies locked in his subconscious, of which there can be no telling. Or as Henry James put it, “Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.” Why should we expect a painter to be able to explain its mystery?

And yet the bleakness of Bacon’s paintings — the screaming heads, the flayed and distorted flesh — is strikingly at odds with his social exuberance. As a host, he could be genial and generous and waspishly funny. Over oysters at Wheeler’s, or caviar and grouse at Claridge’s, Bacon carpes the diem and most of the noctem, with Peppiatt in grateful attendance.

If the painter is vague about his own art, he is magisterial about others’. He admires Velazquez, Giacometti, Picasso; he is respectful of Lucian Freud; the rest — Jackson Pollock (“the old lace-maker”), Matisse (“squalid little forms”), Hockney (“there’s nothing really there”) — he disdains. Abstract art he dismisses as “a free fancy about nothing”. He says that he can’t read novels — “I find them so boring” — yet goes on to profess his “deep” admiration of Proust and Joyce, apparently unaware that they were both novelists. If Peppiatt saw the contradiction he failed (or didn’t dare) to point it out.

Peppiatt makes a starry-eyed chronicler, as besotted with his patron’s fine wine and grub as he is with his closeness to the throne. Yet one does wonder what he could have offered in return to Bacon. The thought occurs to Peppiatt, too, worried that he might just be a “person from Porlock”, forever getting in the way of genius. Beyond an ability to speak French and supply company at a moment’s notice, the young man has very little to recommend him — as Sonia Orwell, another Bacon intimate, would gloweringly point out. But “Francis” seems content to have made him his pet.

Peppiatt proceeds on his girlfriends coming and going, though one is never in doubt that Bacon remains the most important figure in his life — a substitute, moreover, for his own unsatisfactory father, a manic-depressive who bullied the family for years.

The underlying tension between master and protégé keeps the pages turning, though Peppiatt’s prose seldom quickens the pace. He shows no great resistance to a cliché (“over the moon” and “rose-tinted spectacles” are waved through) and his dipping in and out of the present tense doesn’t lend his narrative the freshness he intends.

His social nervousness, which might otherwise have been touching, makes his writing plod the more: “When I’m doing one of my large parties I serve a spicy chicken curry with exotic condiments, much appreciated by my French friends, or for a sit-down dinner I often make a slowly braised boeuf bourguignon, to which in a slight departure from the classic recipe I add mushrooms and top with croutons and crisp-fried parsley — the latter being something I know Francis likes especially, since we had it once in a restaurant on some grilled fish and he pronounced it ‘one of the most delicious things you can possibly eat’.” Monsieur Pooter lives — and cooks too!

Oddly, Peppiatt is at his most readable on Bacon’s painting, the hardest trick of all, and the one area in which he allows his critical discernment the upper hand. Elsewhere his pride and his gratitude smudge the portrait — he never really pays Bacon the tribute of suspecting him.

Their relationship did not have a happy ending. The first cracks opened when Bacon vetoed Peppiatt’s projected biography of him, despite his long service as bag-carrier and Boswelliser. The rift became wider when Peppiatt announced he was about to become a father for the first time. Bacon, pale with fury, reacts to the news as a personal “affront”.

Did Bacon, now old and ill, fear the prospect of “losing” his one-time disciple? Perhaps he had become too attached to the idea of the tragic exit, like that of his troubled friend George Dyer, who killed himself in a Paris hotel bathroom on the eve of Bacon’s 1971 retrospective at the Grand Palais. (Peppiatt’s reminiscence of Dyer, spouting broad cockney-sparrowisms, is pitifully inadequate).

Long goodbyes didn’t suit Francis Bacon, and one wonders if his shade would be any better pleased by his friend’s ongoing parade of memorials.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd, 2015