|

|

The Green Road

By Anne Enright, W.W. Norton & Company, 304 pages, $26.95

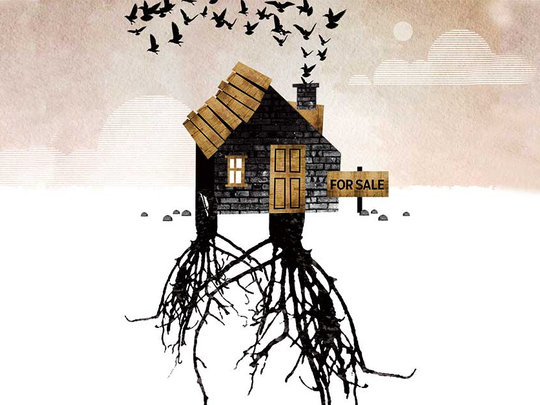

Anne Enright’s new book, the blurb tells us, is set around an enticing moment: matriarch Rosaleen Madigan calling together her grown-up children to discuss the selling of the family house. Families and their particular unhappinesses; Ireland and her madness; houses and inheritance — the very stuff of novels. We anticipate character arcs and plot lines steaming out from the will-making with all the coal-fired, piston-pumping energy of “Bleak House”.

But “The Green Road” is nothing like that. Rosaleen is certainly a fine specimen of matriarchal monster, but she doesn’t get round to the summoning of offspring, let alone the disbursement, until more than halfway through the book. The first part is instead given over to separate episodes in the lives of the four children, each spaced widely from the next, like lights on the long country road of the title.

We begin with Hanna, 12, wandering round her home town in County Clare in 1980 and trying to bridge, on foot and in her mind, the gap between her granny Madigan in an unheated small holding straight from J.M. Synge, and the modernity of her uncle Bart Considine’s chemist’s shop, where “bottom cream” is dispensed and requests for condoms are smugly refused.

The two sides of the family are long estranged: “Grandfather Madigan was shot during the civil war and their grandfather Considine refused to help. The men ran to the Medical Hall looking for ointment and bandages and he just pulled down the blind.”

Hanna’s oldest brother, Dan, is all set to be a priest at this point, but when we join him in 1991 in New York, he has metamorphosed into “Irish Dan”: mercurially reciting Yeats to a table of men, deftly and cruelly moving through and out of the charged dramas of the Aids epidemic. Six years later, Dan’s loved and despised sister Constance is called in for a mammogram, and drives herself along the “green road” to hospital.

As in her earlier novel “The Forgotten Waltz”, Enright casually and superbly evokes the changes that came to Ireland in the 1990s, exemplified in this instance by Constance’s brash husband and his family: “She passed the latest McGrath house: Dessie’s brother the auctioneer’s, who had built a bungalow, high off the road.”

But Enright also weaves in something new, here and throughout the book: a thread of flaming, elemental Irish romanticism. Constance continues: “The slope of raw clay had been ablaze, when her father passed along that way, with red poppies and with those yellow flowers that love broken ground.” Constance thinks briefly of middle brother Emmet, “back from Africa, or wherever, with a scraggy beard and hundred yard stare”, and in 2002 in Mali we catch up with him, trying to balance the demands of starving children and a needy dog; of his sentimental, lovable girlfriend Alice and his terrible drive to do good.

Enright wrote short stories before she wrote novels, and each of these chapters is something like one, though of an unusually lengthy, majestic sort. Each takes place in its own fully realised, strikingly sensuous world. Each has a separate narratorial voice: just behind Constance’s shoulder in her chapter; and chilly with irony for Emmet.

Enright does not try to link the tales in any conventional manner: the siblings think of each other only glancingly; and Constance doesn’t tell us, for instance, when or how Dan gave up the priesthood, though we thirst to know. Any one of these episodes could be read separately, in short, for the wit or the pleasures of the deft prose; but it is part of the miracle of this novel that the stories seem, nevertheless, powerfully part of each other.

How has this been achieved? Perhaps it is simply that the characters are so finely realised that they seem continuous: we feel the pressures on Emmet as coming from the long past, part of the air he breathes; we understand that the absence of all three of Constance’s siblings is an unspoken part of her homemaking; most extraordinary of all, we experience Dan’s gaps and distance as part of his character, his distance from himself. It is not much like a novel, but it is a lot like knowing people; an awful lot like being alive.

The novel-ish crisis does finally arrive, as such moments do in life, and is heralded with declarations and journeys and massive shopping sprees; and passes with a fine display of compulsive bad behaviour, flummery and policemen. When it is over the Madigan siblings have, in a novel-like manner, gained some wisdom. But no one, least of all Rosaleen, can be tucked into an arc in this book; only minor characters are allowed a resolution, and that a brief one, on Facebook.

The episodic, trailing, unclosed ending is perhaps the most brilliant part of this brilliant, devastating, radical novel. Nothing is settled; no one is improved: life and character are as provisional, as mysterious and as rich as they seemed to Hanna at the beginning of the journey, when she walked down the road looking into the windows, each with its “own decoration and its own version of curtains or blinds: a sailboat made of polished horn, a cream tureen with plastic flowers in it, a pink felted plastic cat”.

This is not a book about houses, however lovingly Enright evokes them; it is a book about the road: the green road across the Burren, “the most beautiful road in the world, bar none” — the road to the sea.

–Guardian News & Media Ltd

Kate Clanchy’s recent book is “The Not-Dead and the Saved”